<Back to Index>

- Chemist Leo Hendrik Baekeland, 1863

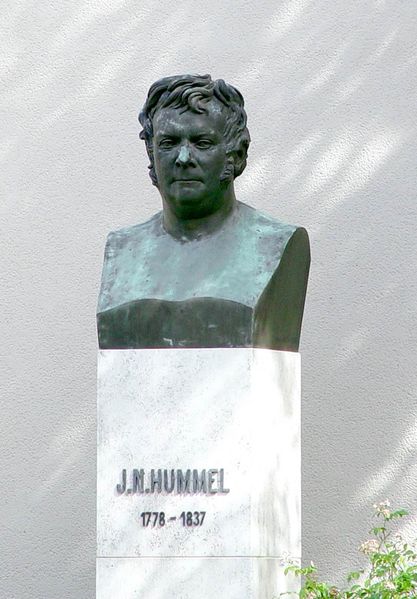

- Composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel, 1778

- Prince of Orange Maurits of Nassau, 1567

PAGE SPONSOR

Johann Nepomuk Hummel or Jan Nepomuk Hummel (November 14, 1778 – October 17, 1837) was an Austrian composer and virtuoso pianist. His music reflects the transition from the Classical to the Romantic musical era.

Hummel was born in Pressburg, Hungary, then a part of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy (now Bratislava, Slovakia). His father, Josef Hummel, was the director of the Imperial School of Military Music in Vienna and the conductor there of Schikaneder's Theater Orchestra; his mother was Slovak. He was named after St. John Nepomucene. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart offered the boy music lessons at the age of 8 after being impressed with his ability. Hummel was taught and housed by Mozart for 2 years free of charge and made his first concert appearance at the age of nine, at one of Mozart's concerts.

Hummel's father then led him on a European tour, arriving in London, where he received instruction from Muzio Clementi and stayed for four years before returning to Vienna. In 1791, Joseph Haydn, who was in London at the same time as young Hummel, composed a sonata in A flat for Hummel, who played its premiere in the Hanover Square Rooms in Haydn's presence. When Hummel finished, Haydn reportedly thanked the young man and gave him a guinea. The outbreak of the French Revolution and the following Terror caused

Hummel to cancel a planned tour through Spain and France. Instead he

returned to Vienna giving concerts along his route. Upon Hummel's

return to Vienna he was taught by Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, Joseph Haydn, and Antonio Salieri. At about this time, young Ludwig van Beethoven arrived

in Vienna and took lessons from Haydn and Albrechtsberger, becoming a

fellow student and a friend. Beethoven's arrival was said to have

nearly destroyed Hummel's self - confidence, though he recovered

without much harm. Despite the fact that Hummel's friendship with

Beethoven was

often marked by ups and downs, the mutual friendship developed into

reconciliation and respect. Before Beethoven's death, Hummel visited

him in Vienna on several occasions, with his wife Elisabeth and pupil Ferdinand Hiller.

Following Beethoven's wishes, Hummel improvised at the great man's

memorial concert. It was at this event that Hummel became good friends

with Franz Schubert. Schubert dedicated his last three piano sonatas to Hummel. However, since both composers were dead by the time of the

sonatas' first publication, the publishers changed the dedication to Robert Schumann, who was still active at the time. In 1804, Hummel succeeded Haydn as Kapellmeister to Prince Esterházy's establishment at Eisenstadt.

He held this post for seven years before being dismissed for neglecting

his duties. Following this, he toured Russia and Europe and married the

opera singer Elisabeth Röckel. They had two sons. Hummel later held the position of Kapellmeister at Stuttgart and Weimar, where he formed a close friendship with Goethe and Schiller, colleagues from the Weimar theater. During Hummel's stay in Weimar, he

made the city into a European musical capital, inviting the best

musicians of the day to visit and make music there. He started one of

the first pension programs for fellow musicians, giving benefit concert tours

when the musicians' retirement fund ran low. In addition, Hummel was

one of the first to fight for musical copyrights against intellectual

pirating. While in Germany, Hummel published A Complete Theoretical and Practical Course of Instruction on the Art of Playing the Piano Forte (1828),

which sold thousands of copies within days of its publication and

brought about a new style of fingering and of playing ornaments. Later

19th century pianistic technique was influenced by Hummel, through his

instruction of Carl Czerny who later taught Franz Liszt. Czerny had first studied with Beethoven, but upon hearing Hummel one evening, decided to give up Beethoven for Hummel. Hummel's influence can also be seen in the early works of Frédéric Chopin and Robert Schumann, and the shadow of Hummel's Piano Concerto in B minor as well as his Piano Concerto in A minor can

be particularly perceived in Chopin's concertos. This is unsurprising,

considering that Chopin must have heard Hummel on one of the latter's

concert tours to Poland and Russia, and that Chopin kept Hummel's piano

concertos in his active repertoire. Harold C. Schonberg, in The Great Pianists, writes "the openings of the Hummel A minor and Chopin E minor concertos are too close to be coincidental". In relation to Chopin's Preludes, Op. 28, Schonberg says: "It also is hard to escape the notion that Chopin was very familiar with Hummel's now forgotten Op. 67, composed in 1815 - a set of twenty - four preludes in all major and minor keys, starting with C major". Robert Schumann also

practiced Hummel (especially the Sonata in F sharp minor, Op. 81). He

later applied to be a pupil to Hummel. Liszt would have liked to study

with Hummel, but Liszt's father Adam refused to pay the high tuition

fee Hummel was used to charging (thus Liszt ended up studying with

Czerny). Czerny, Friedrich Silcher, Ferdinand Hiller, Sigismond Thalberg, Felix Mendelssohn and Adolf von Henselt were among Hummel's most prominent students. Hummel's

music took a different direction from that of Beethoven. Looking

forward, Hummel stepped into modernity through pieces like his Sonata

in F sharp minor, Op. 81, and his Fantasy, Op. 18, for piano. These

pieces are examples where Hummel may be seen to both challenge the

classical harmonic structures and stretch the sonata form.

However, Hummel's vision of music was not iconoclastic. The philosophy

on which Hummel based his actions was to "enjoy the world by giving joy

to the world". His main oeuvre is for the piano, on which instrument he was one of the great virtuosi of his day. He wrote eight piano concertos, ten piano sonatas (of which four are without opus numbers, and one is still unpublished), eight piano trios, a piano quartet, a piano quintet, a wind octet, a cello sonata, two piano septets, a mandolin concerto, a mandolin sonata, a Trumpet Concerto in E major written for the Keyed trumpet (usually

heard in the more convenient E flat major), a "Grand Bassoon Concerto"

in F, a quartet for clarinet, violin, viola, and cello, four hand piano

music, 22 operas and Singspiels, masses, and much more. The conspicuous lack of a symphony among

Hummel's works may perhaps be explained by the fact that he could not

follow Beethoven's innovations in that field, although that does not

explain why he didn't compose a symphony in, say, the style of Haydn.

But the classical symphony lacks a piano, which might have reduced its

appeal to Hummel, who, as an avid pianist, would consequently write

piano concertos instead. He wrote eight in all; the first two are early

Mozartesque compositions (S. 4/WoO 24 and S. 5) and the later six were

numbered and published with opus numbers (Opp. 36, 85, 89, 110, 113,

and posth 1). Hummel left interesting transcriptions for piano, flute, violin and cello of some of Mozart's piano concertos and symphonies, that have been recently recorded by the German pianist Fumiko Shiraga. In particular, his transcriptions of the Piano Concerto No. 20 and of the Symphony No. 40 have been well received. At

the end of his life, Hummel saw the rise of a new school of young

composers and virtuosi, and found his own music slowly going out of

fashion. His disciplined and clean Clementi style

technique, and his balanced classicism, opposed him to the rising

school of tempestuous bravura displayed by the likes of Liszt and Giacomo Meyerbeer. Composing less and less, but still highly respected and admired, Hummel died peacefully in Weimar in 1837. A freemason (like Mozart), Hummel bequeathed a considerable portion of his famous garden behind his Weimar residence to his masonic lodge. Although

Hummel died famous, with a lasting posthumous reputation apparently

secure, his music was quickly forgotten at the onrush of the Romantic

period, perhaps because his classical ideas were seen as old-fashioned.

Later, during the classical revival of the early 20th century, Hummel

was passed over. Like Haydn (for whom a revival had to wait until the

second half of the 20th century), Hummel was overshadowed by Mozart.

Due to a rising number of available recordings and an increasing number

of live concerts across the world, it seems admirers of his music are

now growing again in number.