<Back to Index>

- Physicist Eugene Paul "E.P." Wigner, 1902

- Poet Salomėja Bačinskaitė - Bučienė (Nėris), 1904

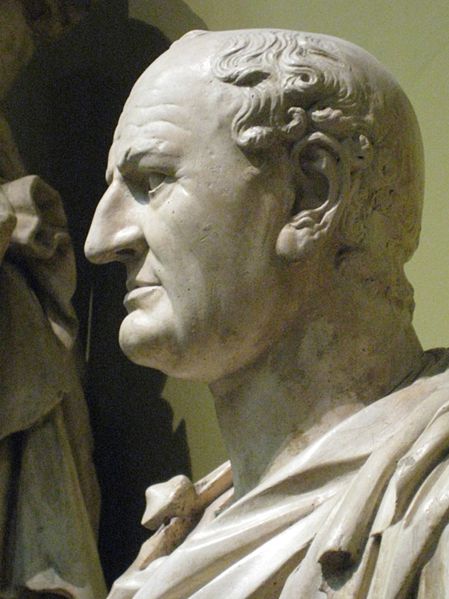

- Emperor of the Roman Empire Titus Flavius Vespasianus, 9

PAGE SPONSOR

Titus Flavius Vespasianus , commonly known as Vespasian (17 November 9 – 23 June 79), was Roman Emperor from 69 AD to 79 AD. Vespasian was the founder of the Flavian dynasty which ruled the empire for a quarter century. Vespasian was descended from a family of equestrians, who rose into the senatorial rank under the emperors of the Julio - Claudian dynasty. Although he attained the standard succession of public offices, holding the consulship in 51 AD, Vespasian became more reputed as a successful military commander, participating in the Roman invasion of Britain in 43, and subjugating Judaea during the Jewish rebellion of 66 AD. While Vespasian was preparing to besiege the city of Jerusalem during the latter campaign, emperor Nero committed suicide, plunging the empire into a year of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors. After the emperors Galba and Otho perished in quick succession, Vitellius became emperor in April 69 AD. In response, the armies in Egypt and Judaea declared Vespasian emperor on July 1. In his bid for imperial power, Vespasian joined forces with Mucianus, the governor of Syria, and Primus, a general in Pannonia. Primus and Mucianus led the Flavian forces against Vitellius, while Vespasian gained control of Egypt. On 20 December, Vitellius was defeated, and the following day Vespasian was declared emperor by the Roman Senate.

Little

information survives about the government during the ten years

Vespasian was emperor. His reign is best known for financial reforms

following the demise of the Julio - Claudian dynasty, the successful

campaign against Judaea, and several ambitious construction projects,

such as the Colosseum. Upon his death in 79, he was succeeded by his eldest son Titus. Vespasian was born in Falacrina, in the Sabine country near Reate. His

family was relatively undistinguished and lacking in pedigree. His

paternal grandfather, Titus Flavius Petro, was the first to distinguish

himself, rising to the rank of centurion and fighting at Pharsalus for Pompey in 48 BC. Subsequently he became a debt collector. Petro's son, Titus Flavius Sabinus, worked as a customs official in the province of Asia and became a money - lender on a small scale among the Helvetii. He gained a reputation as a scrupulous and honest "tax - farmer". Sabinus married up in status, to Vespasia Polla, whose father had risen to prefect of the camp and whose brother became a Senator. Sabinus and Vespasia had three children, the eldest of whom, a girl, died in infancy. The elder boy, Titus Flavius Sabinus entered public life and pursued the cursus honorum. He served in the army as a military tribune in Thrace in 36. The following year he was elected quaestor and served in Crete and Cyrene. He rose through the ranks of Roman public office, being elected aedile on his second attempt in 39 and praetor on his first attempt in 40, taking the opportunity to ingratiate himself with the Emperor Caligula. The

younger boy, Vespasian, seemed far less likely to be successful,

initially not wishing to pursue high public office. He followed in his

brother's footsteps when driven to it by his mother's taunting. During this period he married Flavia Domitilla, the daughter of Flavius Liberalis from Ferentium and the mistress of Statilius Capella, a Roman knight. They had two sons, Titus Flavius Vespasianus (b. 41) and Titus Flavius Domitianus (b. 51), and a daughter, Domitilla (b.

39). His wife Domitilla and his daughter Domitilla both died before

Vespasian became emperor in 69. After the death of his wife, Vespasian

's longstanding mistress, Antonia Caenis, became his wife in all but formal status, a relationship that survived until she died in 75.

In preparation for a quaestorship, Vespasian needed two periods of service in the minor magistracies,

one military and the other public. Vespasian served in the military in

Thrace for about 3 years. On his return to Rome in about 30, he

obtained a post in the vigintivirate, the minor magistracies, most probably in one of the posts in charge of street cleaning. His

early performance was so unsuccessful that Caligula reportedly stuffed

handfuls of muck down his toga to correct the uncleaned Roman streets,

formally his responsibility. During the period of the ascendancy of Sejanus,

there is no record of Vespasian's significant activity in political

events. After completion of a term in the vigintivirate, Vespasian was

entitled to stand for election as quaestor; a senatorial office. But

his lack of political or family influence meant that Vespasian served

as quaestor in one of the provincial posts in Crete, rather than as assistant to important men in Rome. Next he needed to gain a praetorship, carrying the Imperium, but non-patricians and the less well connected had to serve in at least one intermediary post as an aedile or tribune.

Vespasian failed at his first attempt to gain an aedileship but was

successful in his second attempt, becoming an aedile in 38. Despite his

lack of significant family connections or success in office, he

achieved praetorship in either 39 or 40, at the youngest age permitted

(30), during a period of political upheaval in the organisation of

elections. His longstanding relationship with freedwoman Antonia Caenis,

confidential secretary to the Emperor's grandmother and part of the

circle of courtiers and servants round the Emperor, may have

contributed to his success.

Upon the accession of Claudius as emperor in 41, Vespasian was appointed legate of Legio II Augusta, stationed in Germania, thanks to the influence of the Imperial freedman Narcissus. In 43, Vespasian and the II Augusta participated in the Roman invasion of Britain, and he distinguished himself under the overall command of Aulus Plautius. After participating in crucial early battles on the rivers Medway and Thames, he was sent to reduce the south west, penetrating through the modern counties of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall with

the probable objectives of securing the south coast ports and harbours

along with the tin mines of Cornwall and the silver and lead mines of

Somerset. Vespasian marched from Noviomagus Reginorum (Chichester) to subdue the hostile Durotriges and Dumnonii tribes, captured twenty oppida (towns, or more probably hill forts, including Hod Hill and Maiden Castle in Dorset). He also invaded Vectis (the Isle of Wight), finally setting up a fortress and legionary headquarters at Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter).

During this time he injured himself and had not fully recovered until

he went to Egypt. These successes earned him triumphal regalia (ornamenta triumphalia) on his return to Rome. His

success as the legate of a legion, earned him a consulship in 51 after

which he retired from public life, having incurred the enmity of Claudius' wife, Agrippina. He came out of retirement in 63 when he was sent as governor to Africa Province. According to Tacitus, his rule was "infamous and odious" but according to Suetonius, he was "upright and, highly honourable". On one occasion he was pelted with turnips.

Vespasian used his time in North Africa wisely. Usually governorships

were seen by ex-consuls as opportunities to extort huge amounts of

money to regain their wealth that they had spent on their previous

political campaigns. Corruption was so rife, that it was almost

expected that a governor would come back from these appointments with

his pockets full. However, Vespasian used his time in North Africa

making friends instead of money; something that would be far more

valuable in the years to come. During his time in North Africa, he

found himself in financial difficulties and was forced to mortgage his

estates to his brother. To revive his fortunes he turned to the mule trade and gained the nickname mulio (mule driver). Returning from Africa, Vespasian toured Greece in Nero's

retinue, but lost Imperial favour after paying insufficient attention

(some sources suggest he fell asleep) during one of the Emperor's

recitals on the lyre, and found himself in the political wilderness. However, in 66, Vespasian was appointed to suppress the Great Jewish Revolt in Judaea. A revolt there had killed the previous governor and routed Cestius Gallus, the governor of Syria,

when he tried to restore order. Two legions, with eight cavalry

squadrons and ten auxiliary cohorts, were therefore dispatched under

the command of Vespasian while his elder son, Titus, arrived from Alexandria with another. During this time he became the patron of Flavius Josephus, a Jewish resistance leader captured at the Siege of Yodfat who

would go on to write his people's history in Greek. In the end,

thousands of Jews were killed and many towns destroyed by the Romans

who successfully re-established control over Judea. They took Jerusalem

in 70. He is remembered by Josephus, in his "Antiquities of the Jews"

as a fair and humane official, in contrast to the notorious Herod the Great whom Josephus goes to great lengths to demonize. Josephus, while under the patronage of the Roman Emperor, wrote that after the Roman Legio X Fretensis accompanied by Vespasian destroyed Jericho on 21 June 68, he took a group of Jews who could not swim (possibly Essenes from Qumran), fettered them, and threw them into the Dead Sea to test its legendary buoyancy. Sure enough, the Jews shot back up after being thrown in from boats and floated calmly on top of the sea. After the death of Nero in 68, Rome saw a succession of short lived emperors and a year of civil wars. Galba was murdered by Otho, who was defeated by Vitellius. Otho's supporters, looking for another candidate to support, settled on Vespasian. According

to Suetonius, a prophecy ubiquitous in the Eastern provinces claimed

that from Judaea would come the future rulers of the world. Vespasian

eventually believed that this prophecy applied to him, and found a

number of omens, oracles, and portents that reinforced this belief. He

also found encouragement in Mucianus, the governor of Syria; and,

although Vespasian was a strict disciplinarian and reformer of abuses,

Vespasian's soldiers were thoroughly devoted to him. All eyes in the

East were now upon him. Mucianus and the Syrian legions were eager to

support him. While he was at Caesarea, he was proclaimed emperor (1 July 69), first by the army in Egypt under Tiberius Julius Alexander, and then by his troops in Judaea (11 July according to Suetonius, 3 July according to Tacitus). Nevertheless, Vitellius, the occupant of the throne, had Rome's best troops on his side — the veteran legions of Gaul and the Rhineland. But the feeling in Vespasian's favour quickly gathered strength, and the armies of Moesia, Pannonia, and Illyricum soon declared for him, and made him the de facto master of half of the Roman world. While Vespasian himself was in Egypt securing its grain supply, his troops entered Italy from the northeast under the leadership of M. Antonius Primus. They defeated Vitellius's army (which had awaited him in Mevania) at Bedriacum (or Betriacum), sacked Cremona and advanced on Rome. They entered Rome after furious fighting. In the

resulting confusion, the Capitol was destroyed by fire and Vespasian's brother Sabinus was killed by a mob. On receiving the tidings of his rival's defeat and death at Alexandria,

the new emperor at once forwarded supplies of urgently needed grain to

Rome, along with an edict or a declaration of policy, in which he gave

assurance of an entire reversal of the laws of Nero, especially those

relating to treason. While in Egypt he visited the Temple of Serapis, where reportedly he experienced a vision. Later he was confronted by two labourers who were convinced that he possessed a divine power that could work miracles. Vespasian

was declared emperor by the Senate while he was in Egypt in December of

69 (the Egyptians had declared him emperor in June of 69). In the

short term, administration of the empire was given to Mucianus who was aided by Vespasian's son, Domitian.

Mucianus started off Vespasian's rule with tax reform that was to

restore the empire's finances. After Vespasian arrived in Rome in

mid 70, Mucianus continued to press Vespasian to collect as many taxes

as possible. Vespasian

and Mucianus renewed old taxes and instituted new ones, increased the

tribute of the provinces, and kept a watchful eye upon the treasury

officials. The Latin proverb "Pecunia non olet" ("Money does not smell") may have been created when he had introduced a urine tax on

public toilets. By his own example of simplicity of life — he caused

something of a scandal when it was made known he took his own boots off

— he initiated a marked improvement in the general tone of society in

many respects. In early 70, Vespasian was still in Egypt, the source of Rome's grain supply, and had not yet left for Rome. According to Tacitus, his trip was delayed due to bad weather. Modern

historians theorize that Vespasian had been and was continuing to

consolidate support from the Egyptians before departing. Stories of a divine Vespasian healing people circulated in Egypt. During

this period, protests erupted in Alexandria over his new tax policies

and grain shipments were held up. Vespasian eventually restored order

and grain shipments to Rome resumed. In

addition to the uprising in Egypt, unrest and civil war continued in

the rest of the empire in 70. In Judea, rebellion had continued from 66. Vespasian's son, Titus, finally subdued the rebellion with the capture of Jerusalem and destruction of the Jewish Temple in 70. According to Eusebius, Vespasian then ordered all descendants of the royal line of David to

be hunted down, causing the Jews to be persecuted from province to

province. Several modern historians have suggested that Vespasian,

already having been told by Josephus that he was prophesied to become

emperor whilst in Judaea, was probably reacting to other widely known

Messianic prophecies circulating at the time, to suppress any rival

claimants arising from that dynasty. In January of the same year, an uprising occurred in Gaul and Germany, known as the second Batavian Rebellion. This rebellion was headed by Gaius Julius Civilis and Julius Sabinus. Sabinus, claiming he was descended from Julius Caesar,

declared himself emperor of Gaul. The rebellion defeated and absorbed

two Roman legions before it was suppressed by Vespasian's

brother - in - law, Quintus Petillius Cerialis, by the end of 70.

In

mid 70, Vespasian first came to Rome. Vespasian immediately embarked on

a series of efforts to stay in power and prevent future revolts. He

offered gifts to many in the military and much of the public. Soldiers loyal to Vitellius were dismissed or punished. He also restructured the Senatorial and Equestrian orders, removing his enemies and adding his allies. Regional autonomy of Greek provinces was repealed. Additionally, he made significant attempts to control public perception of his rule. Many modern historians note the increased amount of propaganda that appeared during Vespasian's reign. Stories of a supernatural emperor who was destined to rule circulated in the empire. Nearly one-third of all coins minted in Rome under Vespasian celebrated military victory or peace. The word vindex was removed from coins so as not to remind the public of rebellious Vindex. Construction projects bore inscriptions praising Vespasian and condemning previous emperors. A temple of peace was constructed in the forum as well. Vespasian approved histories written under his reign, ensuring biases against him were removed. Vespasian also gave financial rewards to ancient writers. The ancient historians who lived through the period such as Tacitus, Suetonius, Josephus and Pliny the Elder speak suspiciously well of Vespasian while condemning the emperors who came before him. Tacitus

admits that his status was elevated by Vespasian, Josephus identifies

Vespasian as a patron and savior, and Pliny dedicated his Natural Histories to Vespasian's son, Titus. Those

who spoke against Vespasian were punished. A number of stoic

philosophers were accused of corrupting students with inappropriate teachings and were expelled from Rome. Helvidius Priscus, a pro-republic philosopher, was executed for his teachings.

Between

71 and 79, much of Vespasian's reign is a mystery. Historians report

that Vespasian ordered the construction of several buildings in Rome.

Additionally, he survived several conspiracies against him.

Vespasian helped rebuild Rome after the civil war. He added the temple of Peace and the

temple to the Deified Claudius. In 75, he erected a colossal statue of Apollo, begun under Nero, and he dedicated a stage of the theater of Marcellus. He also began construction of the Colosseum. Suetonius claims that Vespasian was met with "constant conspiracies" against him. Only one conspiracy is known specifically, though. In 78 or 79, Eprius Marcellus and Aulus Caecina Alienus attempted to kill Vespasian. Why these men turned against Vespasian is not known.

In 78, Agricola was sent to Britain,

and both extended and consolidated the Roman dominion in that province,

pushing his way into what is now Scotland. In his ninth consulship

Vespasian had a slight illness in Campania and, returning at once to

Rome, he left for Aquae Cutiliae and the country around Reate, where he spent every summer. However, his illness worsened and he developed severe diarrhea. On 23 June of 79, Vespasian was on his deathbed and expiring rapidly,

he demanded that he be helped to stand as he believed "An emperor

should die on his feet". He died of a fever. His purported great wit

can be glimpsed from his last words; Væ, puto deus fio, "Oh! I think I'm becoming a god!".

Vespasian

was known for his wit and his amiable manner alongside his commanding

personality and military prowess. He could be liberal to impoverished

Senators and equestrians and to cities and towns desolated by natural

calamity. He was especially generous to men of letters and

rhetors, several of whom he pensioned with salaries of as much as 1,000 gold pieces a year. Quintilian is said to have been the first public teacher who enjoyed this imperial favor. Pliny the Elder's work, the Natural History, was written during Vespasian's reign, and dedicated to Vespasian's son Titus. Vespasian

distrusted philosophers in general, viewing them as unmanly complainers

who talked too much. It was the idle talk of philosophers, who liked to

glorify the good times of the Republic, that provoked Vespasian into reviving the obsolete penal laws against this profession as a precautionary measure. Only one, Helvidius Priscus,

was put to death after he had repeatedly affronted the Emperor by

studied insults which Vespasian had initially tried to ignore, "I will

not kill a dog that barks at me," were his words on discovering Priscus's public slander. Vespasian

was indeed noted for mildness when dealing with political opposition.

According to Suetonius, he bore the frank language of his friends, the

quips of pleaders, and the impudence of the philosophers with the

greatest patience. Though Licinius Mucianus, a man of disputable

reputation as being the receiver in homosexual sex, treated the emperor

with scant respect, Vespasian never criticised him publicly but

privately uttered the words: "I, at least, am a man." He

was also noted for his benefactions to the people, much money was spent

on public works and the restoration and beautification of Rome: a new

forum, the Temple of Peace, the public baths and the great show piece,

the Colosseum. Vespasian debased the denarius during his reign, reducing the silver purity from 93.5% to 90% — the silver weight dropping from 2.97 grams to 2.87 grams. In modern Romance languages, urinals are still named after him (for example, vespasiano in Italian, and vespasienne in French) probably in reference to a tax he placed on urine collection.