<Back to Index>

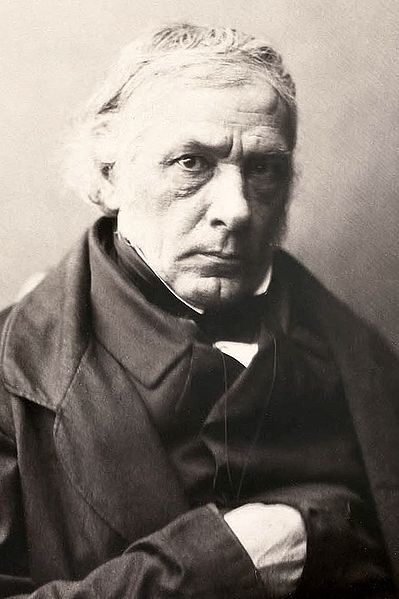

- Philosopher Victor Cousin, 1792

- Novelist Alberto Pincherle (Moravia), 1907

- President of Argentina Arturo Frondizi Ercoli, 1908

PAGE SPONSOR

Victor Cousin (28 November 1792 – 13 January 1867) was a French philosopher. He was a proponent of Scottish Common Sense Realism and had an important influence on French educational policy.

The son of a watchmaker, he was born in Paris, in the Quartier Saint-Antoine. At the age of ten he was sent to the local grammar school, the Lycée Charlemagne, where he studied until he was eighteen. The lycée had a connection with the university, and when Cousin left the secondary school he was "crowned" in the ancient hall of the Sorbonne for the Latin oration delivered by him there, in the general concourse of his school competitors. The classical training of the lycée strongly disposed him to literature. He was already known among his peers for his knowledge of Greek. From the lycée he passed to the Normal School of Paris, where Pierre Laromiguière was then lecturing on philosophy. In the second preface to the Fragments philosophiques, in which he candidly states the varied philosophical influences of his life, Cousin speaks of the grateful emotion excited by the memory of the day in 18.., when he heard Laromiguière for the first time. "That day decided my whole life." Laromiguière taught the philosophy of John Locke and Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, happily modified on some points, with a clarity and grace which in appearance at least removed difficulties, and with a charm of spiritual bonhomie which penetrated and subdued."

Cousin wanted to lecture on philosophy and quickly obtained the position of master of conferences (maître de conférences) in the school. The second great philosophical impulse of his life was the teaching of Pierre Paul Royer - Collard. This teacher, he tells us, "by the severity of his logic, the gravity and weight of his words, turned me by degrees, and not without resistance, from the beaten path of Condillac into the way which has since become so easy, but which was then painful and unfrequented, that of the Scottish philosophy." In 1815 – 1816 Cousin attained the position of suppliant (assistant) to Royer - Collard in the history of modern philosophy chair of the faculty of letters. Another thinker who influenced him at this early period was Maine de Biran, whom Cousin regarded as the unequalled psychological observer of his time in France.

These men strongly influenced Cousin's philosophical thought. To Laromiguière he attributes the lesson of decomposing thought, even though the reduction of it to sensation was inadequate. Royer - Collard taught him that even sensation is subject to certain internal laws and principles which it does not itself explain, which are superior to analysis and the natural patrimony of the mind. De Biran made a special study of the phenomena of the will. He taught him to distinguish in all cognitions, and especially in the simplest facts of consciousness, the voluntary activity in which our personality is truly revealed. It was through this "triple discipline" that Cousin's philosophical thought was first developed, and that in 1815 he began the public teaching of philosophy in the Normal School and in the faculty of letters.

He then took up the study of German, worked at Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, and sought to master the Philosophy of Nature of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling,

which at first greatly attracted him. The influence of Schelling may be

observed very markedly in the earlier form of his philosophy. He

sympathized with the principle of faith of Jacobi, but regarded it as

arbitrary so long as it was not recognized as grounded in reason. In

1817 he went to Germany, and met Hegel at Heidelberg. Hegel's Encyclopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften appeared

the same year, and Cousin had one of the earliest copies. He thought

Hegel not particularly amiable, but the two became friends. The

following year Cousin went to Munich, where he met Schelling for the

first time, and spent a month with him and Jacobi, obtaining a deeper

insight into the Philosophy of Nature. France's

political troubles interfered for a time with his career. In the events

of 1814 – 1815 he took the royalist side. He adopted the views of the

party known as doctrinaire, of which Royer - Collard was the

philosophical leader. He seems to have gone further, and to have

approached the extreme Left. Then came a reaction against liberalism,

and in 1821 – 1822 Cousin was deprived of his offices in the faculty of

letters and in the Normal School. The Normal School was swept away, and

Cousin shared the fate of Guizot,

who was ejected from the chair of history. This enforced abandonment of

public teaching was a mixed blessing: he set out for Germany with a

view to further philosophical study. While at Berlin in

1824 – 1825 he was thrown into prison, either on some ill-defined

political charge at the instance of the French police, or as a result

of an indiscreet conversation. Freed after six months, he remained

under the suspicion of the French government for three years. It was

during this period that he developed what is distinctive in his

philosophical doctrine. His eclecticism, his ontology and his philosophy of history were declared in principle and in most of their salient details in the Fragments philosophiques (Paris,

1826). The preface to the second edition (1833) and the third (1838)

aimed at a vindication of his principles against contemporary

criticism. Even the best of his later books, the Philosophie écossaise, the Du vrai, du beau, et du bien, and the Philosophie de Locke,

were simply matured revisions of his lectures during the period from

1815 to 1820. The lectures on Locke were first sketched in 1819, and

fully developed in the course of 1829. During the seven years when he was prevented from teaching, he produced, besides the Fragments, the edition of the works of Proclus (6 vols., 1820 - 1827), and the works of René Descartes (II vols., 1826). He also commenced his Translation of Plato (13 vols.), which occupied his leisure time from 1825 to 1840. We see in the Fragments very

distinctly the fusion of the different philosophical influences by

which his opinions were finally matured. For Cousin was as eclectic in

thought and habit of mind as he was in philosophical principle and

system. It is with the publication of the Fragments of 1826 that the first great widening of his reputation is associated. In 1827 followed the Cours de l'histoire de la philosophie. In 1828, de Vatimesnil, minister of public instruction in Martignac's

ministry, recalled Cousin and Guizot to their professorial positions in

the university. The three years which followed were the period of

Cousin's greatest triumph as a lecturer. His return to the chair was

the symbol of the triumph of constitutional ideas and was greeted with

enthusiasm. The hall of the Sorbonne was crowded as the hall of no

philosophical teacher in Paris had been since the days of Pierre Abélard.

The lecturer's eloquence mingled with speculative exposition, and he

possessed a singular power of rhetorical climax. His philosophy showed

strikingly the generalizing tendency of the French intellect, and its

logical need of grouping details round central principles. There

was a moral elevation in Cousin's spiritual philosophy which touched

the hearts of his listeners, and seemed to be the basis for higher

development in national literature and art, and even in politics, than

the traditional philosophy of France. His lectures produced more ardent

disciples than those of any other contemporary professor of philosophy.

Judged on his teaching influence, Cousin occupies a foremost place in

the rank of professors of philosophy, who like Jacobi, Schelling and Dugald Stewart have

united the gifts of speculative, expository and imaginative power. The

taste for philosophy — especially its history — was revived in France to an

extent unknown since the 17th century.

Among those influenced by Cousin were Théodore Simon Jouffroy, Jean Philibert Damiron, Garnier, Pierre - Joseph Proudhon, Jules Barthelemy Saint - Hilaire, Felix Ravaisson - Mollien, Charles de Rémusat, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Jules Simon, Adolphe Franck and Patrick Edward Dove,

who dedicated his "The Theory of Human Progression" to him — Jouffroy and

Damiron were first fellow followers, students and then disciples.

Jouffroy always kept firm to the early — the French and Scottish — impulses

of Cousin's teaching. Cousin continued to lecture for two and a half

years after his return to the chair. Sympathizing with the revolution

of July, he was at once recognized by the new government as a friend of

national liberty. Writing in June 1833 he explains both his

philosophical and his political position: "I had the advantage of

holding united against me for many years both the sensational and the theological school. In 1830 both schools descended into the arena of politics. The

sensational school quite naturally produced the demagogic party, and

the theological school became quite as naturally absolutism, safe to

borrow from time to time the mask of the demagogue in order the better

to reach its ends, as in philosophy it is by scepticism that it

undertakes to restore theocracy. On the other hand, he who combated any

exclusive principle in science was bound to reject also any exclusive

principle in the state, and to defend representative government." The

most important work he accomplished during this period was the

organization of primary instruction. It was to the efforts of Cousin

that France owed her advance, in relation to primary education, between

1830 and 1848. Prussia primary and Saxony had

set the national example, and France was guided into it by Cousin.

Forgetful of national calamity and of personal wrong, he looked to

Prussia as affording the best example of an organized system of

national education; and he was persuaded that "to carry back the

education of Prussia into France afforded a nobler (if a bloodless)

triumph than the trophies of Austerlitz and Jena."

In the summer of 1831, commissioned by the government, he visited

Frankfort and Saxony, and spent some time in Berlin. The result was a

series of reports to the minister, afterwards published as Rapport sur Vital de l'instruction publique dans quelques pays de l'Allemagne et particulièrement en Prusse (also De l'instruction publique en Hollande,

1837) His views were readily accepted on his return to France, and soon

afterwards through his influence there was passed the law of primary

instruction. In the words of the Edinburgh Review (July

1833), these documents "mark an epoch in the progress of national

education, and are directly conducive to results important not only to

France but to Europe." The Report was translated into English by Mrs

Sarah Austin in 1834. The translation was frequently reprinted in the United States of America. The legislatures of New Jersey and Massachusetts distributed it in the schools at the expense of the states. Cousin remarks that,

among all the literary distinctions which he had received, "None has

touched me more than the title of foreign member of the American

Institute for Education." To the enlightened views of the ministries of François Guizot and Adolphe Thiers under

the citizen - king, and to the zeal and ability of Cousin in the work

of organization, France owes what is best in her system of primary

education, -- a national interest which had been neglected under the French Revolution,

the Empire and the Restoration. In the first

two years of the reign of Louis Philippe more was done for the

education of the people than had been either sought or accomplished in

all the history of France. In defence of university studies he stood

manfully forth in the chamber of peers in 1844, against the clerical

party on the one hand and the levelling or Philistine party on the

other. His speeches on this occasion were published in a tractate Défense de l'université et de la philosophie (1844 and 1845). This

period of official life from 1830 to 1848 was spent, so far as

philosophical study was concerned, in revising his former lectures and

writings, in maturing them for publication or reissue, and in research

into certain periods of the sophical history of philosophy. In 1835

appeared De la Métaphysique d'Aristote, suivi d'un essai de traduction du premier et du douzième livres; in 1836, Cours de philosophie professé à la faculté des lettres pendant l'année 1818, and Œuvres inédites d'Abélard. This Cours de philosophie appeared later in 1854 as Du vrai, du beau, et du bien. From 1825 to 1840 appeared Cours de l'histoire de la philosophie, in 1829 Manuel de l'histoire de la philosophie de Tennemann, translated from the German. In 1840 – 1841 we have Cours d'histoire de la philosophie morale au XVIIIe siècle (5 vols.). In 1841 appeared his edition of the Œuvres philosophiques de Maine-de-Biran; in 1842, Leçons de philosophie sur Kant (Eng. trans. AG Henderson, 1854), and in the same year Des Pensées de Pascal. The Nouveaux fragments were gathered together and republished in 1847. Later, in 1859, appeared Petri Abaelardi Opera. During

this period Cousin seems to have turned with fresh interest to those

literary studies which he had abandoned for speculation under the

influence of Laromiguière and Royer - Collard. To this renewed

interest we owe his studies of men and women of note in France in the

17th century. As the results of his work in this line, we have, besides

the Des Pensées de Pascal, 1842, Audes sur les femmes et la société du XVII siècle 1853. He has sketched Jacqueline Pascal (1844), Madame de Longueville (1853), the marquise de Sable (1854), the duchesse de Chevreuse (1856), Madame de Hautefort (1856). When the reign of Louis Philippe came

to a close through the opposition of his ministry, with Guizot at its

head, to the demand for electoral reform and through the policy of the

Spanish marriages, Cousin, who was opposed to the government on these

points, lent his sympathy to Cavaignac and the Provisional government.

He published a pamphlet entitled Justice et charite, the purport of

which showed the moderation of his political views. It was markedly

anti - socialistic. But from this period he passed almost entirely from

public life, and ceased to wield the personal influence which he had

done during the preceding years. After the coup d'état of

2 December, he was deprived of his position as permanent member of the

superior council of public instruction. From Napoleon and the Empire he

stood aloof. A decree of 1852 placed him along with Guizot and

Villemain in the rank of honorary professors. His sympathies were

apparently with the monarchy, under certain constitutional safeguards.

Speaking in 1853 of the political issues of the spiritual philosophy

which he had taught during his lifetime, he says, -- "It conducts human

societies to the true republic, that dream of all generous souls, which

in our time can be realized in Europe only by constitutional monarchy."

During

the last years of his life he occupied a suite of rooms in the

Sorbonne, where he lived simply and unostentatiously. The chief feature

of the rooms was his noble library, the cherished collection of a

lifetime. He died at Cannes on

13 January 1867, in his seventy - fifth year. In the front of the

Sorbonne, below the lecture rooms of the faculty of letters, a tablet

records an extract from his will, in which he bequeaths his noble and

cherished library to the halls of his professorial work and triumphs.