<Back to Index>

- Explorer Andrés de Urdaneta, 1498

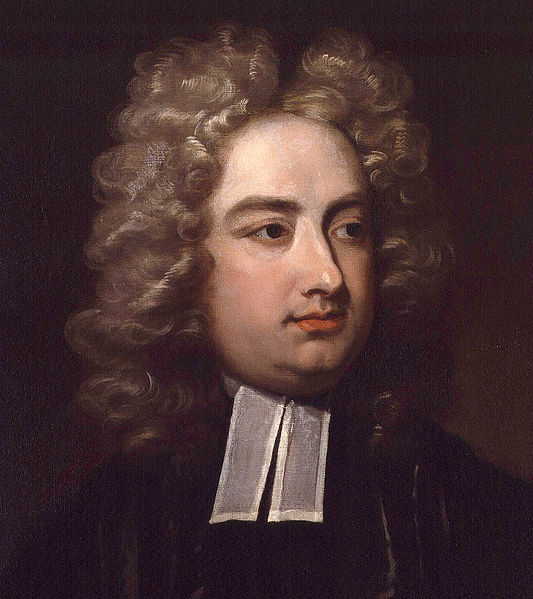

- Writer Jonathan Swift, 1667

- Field Marshal of the Luftwaffe Albert Kesselring, 1885

PAGE SPONSOR

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo - Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who became Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

He is remembered for works such as Gulliver's Travels, A Modest Proposal, A Journal to Stella, Drapier's Letters, The Battle of the Books, An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity, and A Tale of a Tub. Swift is probably the foremost prose satirist in the English language, and is less well known for his poetry. Swift originally published all of his works under pseudonyms — such as Lemuel Gulliver, Isaac Bickerstaff, M.B. Drapier — or anonymously. He is also known for being a master of two styles of satire: the Horatian and Juvenalian styles. Jonathan Swift was born at No. 7, Hoey's Court, Dublin, and was the second child and only son of Jonathan Swift (a second cousin of John Dryden)

and wife Abigail Erick (or Herrick), paternal grandson of Thomas Swift

and wife Elizabeth Dryden, daughter of Nicholas Dryden (brother of Sir Erasmus Dryden, 1st Baronet Dryden)

and wife Mary Emyley. His father was Irish born and his mother was the

sister of the vicar of Frisby - on - the - Wreake, England. Swift

arrived

seven months after his father's untimely death. Most of the facts of

Swift's early life are obscure, confused and sometimes contradictory.

It is widely believed that his mother returned to England when Jonathan

was still very young, then leaving him to be raised by his father's

family. His uncle Godwin took primary responsibility for the young

Jonathan, sending him with one of his cousins to Kilkenny College (also attended by the philosopher George Berkeley). In 1682 he attended Dublin University (Trinity College, Dublin), receiving his B.A. in 1686. Swift was studying for his Master's degree when political troubles in Ireland surrounding the Glorious Revolution forced him to leave for England in 1688, where his mother helped him get a position as secretary and personal assistant of Sir William Temple at Moor Park, Farnham. Temple was an English diplomat who, having arranged the Triple Alliance of 1668,

retired from public service to his country estate to tend his gardens

and write his memoirs. Gaining the confidence of his employer, Swift

"was often trusted with matters of great importance." Within three years of their acquaintance, Temple had introduced his secretary to William III, and sent him to London to urge the King to consent to a bill for triennial Parliaments. When Swift took up his residence at Moor Park, he met Esther Johnson,

then eight years old, the fatherless daughter of one of the household

servants. Swift acted as her tutor and mentor, giving her the nickname

"Stella", and the two maintained a close but ambiguous relationship for

the rest of Esther's life. Swift

left Temple in 1690 for Ireland because of his health, but returned to

Moor Park the following year. The illness, fits of vertigo or

giddiness — now known to be Ménière's disease — would continue to plague Swift throughout his life. During this second stay with Temple, Swift received his M.A. from Hertford College, Oxford in

1692. Then, apparently despairing of gaining a better position through

Temple's patronage, Swift left Moor Park to become an ordained priest

in the Established Church of Ireland and in 1694 he was appointed to the prebend of Kilroot in the Diocese of Connor, with his parish located at Kilroot, near Carrickfergus in County Antrim. Swift

appears to have been miserable in his new position, being isolated in a

small, remote community far from the centres of power and influence.

While at Kilroot, however, Swift may well have become romantically

involved with Jane Waring. A letter from him survives, offering to

remain if she would marry him and promising to leave and never return

to Ireland if she refused. She presumably refused, because Swift left

his post and returned to England and Temple's service at Moor Park in

1696, and he remained there until Temple's death. There he was employed

in helping to prepare Temple's memoirs and correspondence for

publication. During this time Swift wrote The Battle of the Books, a satire responding to critics of Temple's Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning (1690). Battle was however not published until 1704. On

27 January 1699 Temple died. Swift stayed on briefly in England to

complete the editing of Temple's memoirs, and perhaps in the hope that

recognition of his work might earn him a suitable position in England.

However, Swift's work made enemies of some of Temple's family and

friends who objected to indiscretions included in the memoirs. His next

move was to approach King William directly, based on his imagined

connection through Temple and a belief that he had been promised a

position. This failed so miserably that he accepted the lesser post of

secretary and chaplain to the Earl of Berkeley,

one of the Lords Justices of Ireland. However, when he reached Ireland

he found that the secretaryship had already been given to another. But

he soon obtained the living of Laracor, Agher, and Rathbeggan, and the

prebend of Dunlavin in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. At Laracor, a mile or two from Trim, County Meath,

and twenty miles (32 km) from Dublin, Swift ministered to a

congregation of about fifteen people, and had abundant leisure for

cultivating his garden, making a canal (after the Dutch fashion of Moor

Park), planting willows, and rebuilding the vicarage. As chaplain to

Lord Berkeley, he spent much of his time in Dublin and traveled to

London frequently over the next ten years. In 1701, Swift published,

anonymously, a political pamphlet, A Discourse on the Contests and Dissentions in Athens and Rome. In February 1702, Swift received his Doctor of Divinity degree from Trinity College, Dublin. That spring he traveled to England and returned to Ireland in October, accompanied by Esther Johnson — now

twenty years old — and his friend Rebecca Dingley, another member of

William Temple's household. There is a great mystery and controversy

over Swift's relationship with Esther Johnson nicknamed "Stella". Many hold that they were secretly married in 1716. During his visits to England in these years Swift published A Tale of a Tub and The Battle of the Books (1704) and began to gain a reputation as a writer. This led to close, lifelong friendships with Alexander Pope, John Gay, and John Arbuthnot, forming the core of the Martinus Scriblerus Club (founded in 1713). Swift

became increasingly active politically in these years. From 1707 to

1709 and again in 1710, Swift was in London, unsuccessfully urging upon

the Whig administration of Lord Godolphin the claims of the Irish clergy to the First - Fruits and Twentieths ("Queen

Anne's Bounty"), which brought in about £2,500 a year, already

granted to their brethren in England. He found the opposition Tory leadership

more sympathetic to his cause and Swift was recruited to support their

cause as editor of the Examiner when they came to power in 1710. In

1711, Swift published the political pamphlet "The Conduct of the

Allies," attacking the Whig government for its inability to end the

prolonged war with France. The incoming Tory government conducted

secret (and illegal) negotiations with France, resulting in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) ending the War of the Spanish Succession. Swift was part of the inner circle of the Tory government, and often acted as mediator between Henry St. John (Viscount Bolingbroke) the secretary of state for foreign affairs (1710 – 15) and Robert Harley (Earl

of Oxford) lord treasurer and prime minister (1711 – 1714). Swift

recorded his experiences and thoughts during this difficult time in a

long series of letters to Esther Johnson, later collected and published

as The Journal to Stella. The animosity between the two Tory leaders eventually led to the dismissal of Harley in 1714. With the death of Queen Anne and accession of George I that

year, the Whigs returned to power and the Tory leaders were tried for

treason for conducting secret negotiations with France. Also

during these years in London, Swift became acquainted with the

Vanhomrigh family and became involved with one of the daughters, Esther,

yet another fatherless young woman and another ambiguous relationship

to confuse Swift's biographers. Swift furnished Esther with the

nickname "Vanessa" and she features as one of the main characters in

his poem Cadenus and Vanessa. The poem and their correspondence suggests that Esther was infatuated with

Swift, and that he may have reciprocated her affections, only to regret

this and then try to break off the relationship. Esther followed Swift

to Ireland in 1714, where there appears to have been a confrontation,

possibly involving Esther Johnson. Esther Vanhomrigh died in 1723 at

the age of 35. Another lady with whom he had a close but less intense

relationship was Anne Long, a toast of the Kit - Cat Club. Before

the fall of the Tory government, Swift hoped that his services would be

rewarded with a church appointment in England. However, Queen Anne

appeared to have taken a dislike to Swift and thwarted these efforts.

The best position his friends could secure for him was the Deanery of

St. Patrick's, Dublin. With the return of the Whigs, Swift's best move

was to leave England and he returned to Ireland in disappointment, a

virtual exile, to live "like a rat in a hole". Once

in Ireland, however, Swift began to turn his pamphleteering skills in

support of Irish causes, producing some of his most memorable works: Proposal for Universal Use of Irish Manufacture (1720), Drapier's Letters (1724), and A Modest Proposal (1729), earning him the status of an Irish patriot. Also during these years, he began writing his masterpiece, Travels

into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts, by Lemuel

Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships, better known as Gulliver's Travels.

Much of the material reflects his political experiences of the

preceding decade. For instance, the episode in which the giant Gulliver

puts out the Lilliputian palace fire by urinating on it can be seen as

a metaphor for the Tories' illegal peace treaty; having done a good

thing in an unfortunate manner. In 1726 he paid a long - deferred visit

to London, taking with him the manuscript of Gulliver's Travels. During his visit he stayed with his old friends Alexander Pope, John Arbuthnot and John Gay,

who helped him arrange for the anonymous publication of his book. First

published in November 1726, it was an immediate hit, with a total of

three printings that year and another in early 1727. French, German,

and Dutch translations appeared in 1727, and pirated copies were

printed in Ireland. Swift

returned to England one more time in 1727 and stayed with Alexander

Pope once again. The visit was cut short when Swift received word that

Esther Johnson was dying and rushed back home to be with her. On 28

January 1728, Esther Johnson died; Swift had prayed at her bedside,

even composing prayers for her comfort. Swift could not bear to be

present at the end, but on the night of her death he began to write his The Death of Mrs. Johnson.

He was too ill to attend the funeral at St. Patrick's. Many years

later, a lock of hair, assumed to be Esther Johnson's, was found in his

desk, wrapped in a paper bearing the words, "Only a woman's hair." Death became a frequent feature in Swift's life from this point. In 1731 he wrote Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift, his own obituary published in 1739. In 1732, his good friend and collaborator John Gay died.

In 1735, John Arbuthnot, another friend from his days in London, died.

In 1738 Swift began to show signs of illness, and in 1742 he appears to

have suffered a stroke, losing the ability to speak and realizing his

worst fears of becoming mentally disabled. ("I shall be like that

tree," he once said, "I shall die at the top.") To protect him from

unscrupulous hangers on, who had begun to prey on the great man, his

closest companions had him declared of "unsound mind and memory."

However, it was long believed by many that Swift was really insane at

this point. In his book Literature and Western Man, author J.B. Priestley even cites the final chapters of Gulliver's Travels as proof of Swift's approaching "insanity". In part VIII of his series, The Story of Civilization, Will Durant describes the final years of Swift's life as such: "Definite

symptoms of madness appeared in 1738. In 1741 guardians were appointed

to take care of his affairs and watch lest in his outbursts of violence

he should do himself harm. In 1742 he suffered great pain from the

inflammation of his left eye, which swelled to the size of an egg; five

attendants had to restrain him from tearing out his eye. He went a whole year without uttering a word." In

1744, Alexander Pope died. Then, on October 19, 1745, Swift died. After

being laid out in public view for the people of Dublin to pay their

last respects, he was buried in his own cathedral by Esther Johnson's

side, in accordance with his wishes. The bulk of his fortune (twelve

thousand pounds) was left to found a hospital for the mentally ill,

originally known as St. Patrick’s Hospital for Imbeciles, which opened

in 1757, and which still exists as a psychiatric hospital. Jonathan Swift wrote his own epitaph: The literal translation of which is: "Here is laid the Body of Jonathan Swift, Doctor of Sacred Theology, Dean of this Cathedral Church, where fierce

Indignation can no longer injure the Heart. Go forth, Voyager, and

copy, if you can, this vigorous (to the best of his ability) Champion

of Liberty. He died on the 19th Day of the Month of October, A.D. 1745,

in the 78th Year of his Age." William Butler Yeats poetically translated it from the Latin as: Swift's first major prose work, A Tale of a Tub,

demonstrates many of the themes and stylistic techniques he would

employ in his later work. It is at once wildly playful and funny while

being pointed and harshly critical of its targets. In its main thread,

the Tale recounts

the exploits of three sons, representing the main threads of

Christianity, who receive a bequest from their father of a coat each,

with the added instructions to make no alterations whatsoever. However,

the sons soon find that their coats have fallen out of current fashion,

and begin to look for loopholes in their father's will that will let

them make the needed alterations. As each finds his own means of

getting around their father's admonition, they struggle with each other

for power and dominance. Inserted into this story, in alternating

chapters, the narrator includes a series of whimsical "digressions" on

various subjects. In 1690, Sir William Temple, Swift's patron, published An Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning a defense of classical writing holding up the Epistles of Phalaris as an example. William Wotton responded to Temple with Reflections upon Ancient and Modern Learning (1694) showing that the Epistles were a later forgery. A response by the supporters of the Ancients was then made by Charles Boyle (later the 4th Earl of Orrery and father of Swift's first biographer). A further retort on the Modern side came from Richard Bentley, one of the pre-eminent scholars of the day, in his essay Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris (1699). However, the final words on the topic belong to Swift in his Battle of the Books (1697, published 1704) in which he makes a humorous defense on behalf of Temple and the cause of the Ancients. In 1708, a cobbler named John Partridge published a popular almanac of astrological predictions. Because Partridge falsely determined the deaths of several church officials, Swift attacked Partridge in Predictions For The Ensuing Year by Isaac Bickerstaff,

a parody predicting that Partridge would die on March 29. Swift

followed up with a pamphlet issued on March 30 claiming that Partridge

had in fact died, which was widely believed despite Partridge's

statements to the contrary. According to other sources, Richard

Steele uses the personae of Isaac Bickerstaff and was the one who wrote

about the "death" of John Partridge and published it in The Spectator, not Jonathan Swift.* Drapier's Letters (1724) was a series of pamphlets against the monopoly granted by the English government to William Wood to provide the Irish with copper coinage.

It was widely believed that Wood would need to flood Ireland with

debased coinage in order make a profit. In these "letters" Swift posed

as a shop-keeper — a draper — in order to criticize the plan. Swift's

writing was so effective in undermining opinion in the project that a

reward was offered by the government to anyone disclosing the true

identity of the author. Though hardly a secret (on returning to Dublin

after one of his trips to England, Swift was greeted with a banner,

"Welcome Home, Drapier") no one turned Swift in. The government

eventually resorted to hiring none other than Sir Isaac Newton to

certify the soundness of Wood's coinage to counter Swift's accusations.

In "Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift" (1739) Swift recalled this as one

of his best achievements. Gulliver's Travels,

a large portion of which Swift wrote at Woodbrook House in County

Laois, was published in 1726. It is regarded as his masterpiece. As

with his other writings, the Travels was

published under a pseudonym, the fictional Lemuel Gulliver, a ship's

surgeon and later a sea captain. Some of the correspondence between

printer Benj. Motte and Gulliver's also fictional cousin negotiating

the book's publication has survived. Though it has often been

mistakenly thought of and published in bowdlerized form as a children's book, it is a great and sophisticated satire of human nature based on Swift's experience of his times. Gulliver's Travels is

an anatomy of human nature, a sardonic looking glass, often criticized

for its apparent misanthropy. It asks its readers to refute it, to deny

that it has adequately characterized human nature and society. Each of

the four books — recounting four voyages to mostly fictional exotic

lands — has a different theme, but all are attempts to deflate human

pride. Critics hail the work as a satiric reflection on the

shortcomings of Enlightenment thought. In 1729, Swift published A Modest Proposal for

Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland Being a Burden to

Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public, a satire in

which the narrator, with intentionally grotesque logic, recommends that

Ireland's poor escape their poverty by selling their children as food

to the rich: ”I have been assured by a very knowing American of my

acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a

year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food...” Following

the satirical form, he introduces the reforms he is actually suggesting

by deriding them: Therefore

let no man talk to me of other expedients... taxing our

absentees... using [nothing] except what is of our own growth and

manufacture... rejecting... foreign luxury... introducing a vein of

parsimony, prudence and temperance... learning to love our

country... quitting our animosities and factions... teaching landlords to

have at least one degree of mercy towards their tenants.... Therefore I

repeat, let no man talk to me of these and the like expedients, 'till

he hath at least some glympse of hope, that there will ever be some

hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.