<Back to Index>

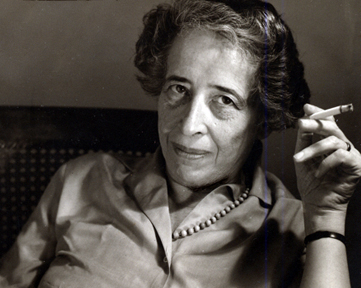

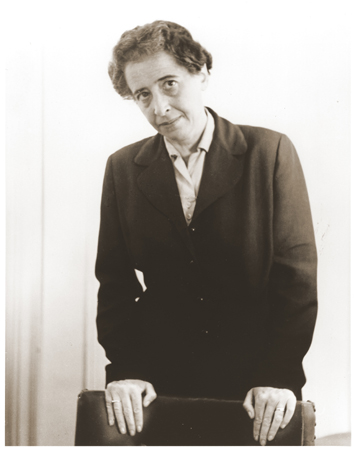

- Political Theorist Hannah Arendt, 1906

- Composer Ernest Pingoud, 1887

- 34th President of the United States Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower, 1890

PAGE SPONSOR

Hannah Arendt (October 14, 1906 – December 4, 1975) was an influential German Jewish political theorist. She has often been described as a philosopher, although she refused that label on the grounds that philosophy is concerned with "man in the singular." She described herself instead as a political theorist because her work centers on the fact that "men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world". Arendt's work deals with the nature of power, and the subjects of politics, authority, and totalitarianism.

Hannah Arendt was born into a family of secular German Jews in the city of Linden (now part of Hannover), and grew up in Königsberg (the birthplace of Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant, in 1946 renamed as Kaliningrad and annexed to the Soviet Union), and Berlin.

At the University of Marburg, she studied philosophy with Martin Heidegger, with whom, as related by her only German Jewish classmate Hans Jonas, she embarked on a long, stormy and romantic relationship for which she was later criticized because of Heidegger's support for the Nazi party while he was rector of Freiburg University.

In the wake of one of their breakups, Arendt moved to Heidelberg, where she wrote her dissertation on the concept of love in the thought of Saint Augustine, under the existentialist philosopher - psychologist Karl Jaspers, then married to a German Jewish woman. She married Günther Stern, later known as Günther Anders, in 1929 in Berlin (they divorced in 1937).

The dissertation was published the same year, but Arendt was prevented from habilitating, a prerequisite for teaching in German universities, because she was Jewish. She worked for some time researching anti-Semitism before being interrogated by the Gestapo, and thereupon fled Germany for Paris. There she met and befriended the literary critic and Marxist philosopher Walter Benjamin, her first husband's cousin. While in France, Arendt worked to support and aid Jewish refugees. She was imprisoned in Camp Gurs but was able to escape after a couple of weeks.

However, with the German military occupation of northern France during World War II, and the deportation of Jews to Nazi concentration camps, even by the Vichy collaborator regime in the unoccupied south, Arendt was forced to flee France. In 1940, she married the German poet and Marxist philosopher Heinrich Blücher, by then a former Communist Party member.

In 1941, Arendt escaped with her husband and her mother to the United States with the assistance of the American diplomat Hiram Bingham IV, who (illegally) issued life saving visas to her and around 2500 other Jewish refugees, and an American, Varian Fry, who paid for her travels and helped in securing these visas. Arendt then became active in the German - Jewish community in New York. From 1941 to 1945, she wrote a column for the German language Jewish newspaper, Aufbau. From 1944, she directed research for the Commission of European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction and traveled frequently to Germany in this capacity.

After World War II she returned to Germany and worked for Youth Aliyah, an organization that had saved thousands of children from the Holocaust. She became a close friend of Karl Jaspers and his Jewish wife, developing a deep intellectual friendship with him and began corresponding with Mary McCarthy.

In 1950, she became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Arendt served as a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, Princeton University and Northwestern University. She also served as a professor on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago, as well as at The New School in New York City, and served as a fellow on the faculty at Yale University and Wesleyan University in the Center for Advanced Studies (1961 – 1962,1962 – 1963). At Princeton, she became the first woman appointed to a full professorship, a decade prior to that university's first admission of female students (1969).

She died at age 69 in 1975, and was buried at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, where her husband taught for many years.

Arendt was instrumental in the creation of Structured Liberal Education (SLE) at Stanford University. She wrote a letter to the then president of Stanford University to convince the university to enact Mark Mancall's vision of a residentially based humanities program. Arendt theorizes freedom as public, performative and associative, drawing on examples from the Greek "polis", American townships, the Paris Commune, the civil rights movements of

the 1960s, and the Hungarian uprising of 1956 to illustrate this

conception of freedom. Another key concept in her work is "natality",

which is the capacity to bring something new into the world, such as

the founding of a government that endures. Natality signs the

contingent, indeterminate and so political future that we don't know

anything about. Arendt's first major book was The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), which traced the roots of Stalinist Communism and Nazism in both anti-Semitism and imperialism.

The book was controversial because it suggested, arguably, that an

essential identity existed between the two phenomena. She further

contends that Jewry was not the operative factor in the Holocaust, but

merely a convenient proxy. Totalitarianism in Germany, in the end, was

about megalomania and consistency, not eradicating Jews. Arguably her most influential work, The Human Condition (1958),

distinguishes between labour, work, and action, and explores the

implications of these distinctions. These categories, which attempt to

bridge the gap between ontological and sociological structures, are

rigidly delineated. Her theory of political action, corresponding to

the existence of a public realm, is extensively developed in this work.

While Arendt concerns labour and work in the realm of "the social", she

favors the human condition of action as "the political" that is both

existential and aesthetic. Another of Arendt's important books is the collection of essays Men in Dark Times.

These intellectual biographies provide insight into the lives of some

of the creative and moral figures of the 20th century, among them Walter Benjamin, Karl Jaspers, Rosa Luxemburg, Hermann Broch, Pope John XXIII, and Isak Dinesen. In her reporting of the Eichmann trial for The New Yorker, which evolved into Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), she coined the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe Eichmann. She raised the question of whether evil is

radical or simply a function of thoughtlessness — the tendency of

ordinary people to obey orders and conform to mass opinion without

critically thinking about the results of their action or inaction. Arendt was extremely critical of the way that Israel conducted the trial. She was also critical of the way that many Jewish leaders (notably M.C. Rumkowski) acted during the Holocaust,

which caused an enormous controversy and resulted in a great deal of

animosity directed toward Arendt within the Jewish community. Her friend Gershom Scholem, a major scholar of Jewish Mysticism, broke off relations with her. Arendt was criticized by many Jewish

public figures, who charged her with coldness and lack of sympathy for

the victims of the Shoah. Due to this lingering criticism, her book has only recently been translated into Hebrew. Arendt ended the book by endorsing the execution of Eichmann, writing: Arendt published another book in the same year that was controversial in its own right: On Revolution, a study of the two most famous revolutions of the 18th century. Arendt went against the grain of Marxist and leftist thought by contending that the American Revolution was a successful revolution, whereas the French Revolution was

not. When the masses of France gained the sympathy of revolutionaries,

the French Revolution turned away from the legal stability of

constitutional government and toward the lawless satisfaction of the

constantly regenerating economic needs of these masses. Some saw in

this argument a post Holocaust anti-French sentiment. Nevertheless, it

was inveterate in the history of political philosophy, echoing that of Edmund Burke. Arendt

also argued that the revolutionary spirit endemic to the founding had

not been preserved in America because the majority of people had no

role to play in politics other than voting. She admired Thomas Jefferson's idea of dividing counties into townships, similar to the soviets that appeared during the Russian Revolution. Arendt's interest in such a "council system", which she saw as the only alternative to the state, continued all her life. Her posthumous book, The Life of the Mind (1978, edited by Mary McCarthy), was incomplete at her death. Stemming from her Gifford Lectures at the University of Aberdeen in

Scotland, this book focuses on the mental faculties of thinking and

willing (in a sense moving beyond her previous work concerning the vita activa). In her discussion of thinking, she focuses mainly on Socrates and his notion of thinking as a solitary dialogue between me and myself.

This appropriation of Socrates leads her to introduce novel concepts of

conscience (which gives no positive prescriptions, but instead tells me

what I cannot do if I would remain friends with myself when I re-enter

the two-in-one of thought where I must render an account of my actions

to myself) and morality (an entirely negative enterprise concerned with

non-participation in certain actions for the sake of remaining friends

with one's self). In her volume on Willing, Arendt, relying heavily on

Augustine's notion of the will, discusses the will as an absolutely

free mental faculty that makes new beginnings possible. In the third volume, Arendt was planning to engage the faculty of judgment by appropriating Kant's Critique of Judgment;

however, she did not live to write it. Nevertheless, although we will

never fully understand her notion of judging, Arendt did leave us with

manuscripts ("Thinking and Moral Considerations", "Some Questions on

Moral Philosophy,") and lectures (Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy ) concerning her thoughts on this mental faculty. The first two articles were edited and published by Jerome Kohn, who was an assistant of Arendt and is a director of Hannah Arendt Center at The New School, and the last was edited and published by Ronald Beiner, who is a professor of political science at the University of Toronto. Her personal library was deposited at Bard College at the Stevenson Library in 1976, and includes approximately 4,000 books, ephemera, and pamphlets from Arendt's last apartment. The college has begun

digitally archiving some of the collection.