<Back to Index>

- Philosopher John Dewey, 1859

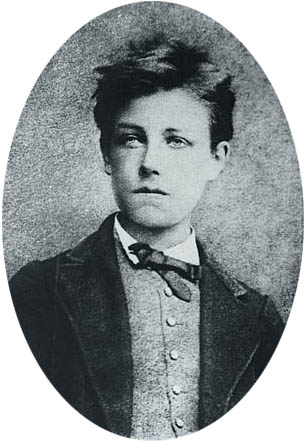

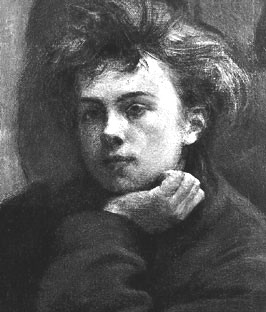

- Poet Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud, 1854

- King of Poland Stanisław I Leszczyński, 1677

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (20 October 1854 – 10 November 1891) was a French poet. Born in Charleville, Ardennes, he produced

his best known works while still in his late teens — Victor Hugo described him at the time as "an infant Shakespeare" — and gave up

creative writing altogether before the age of 21. As part of the decadent movement, Rimbaud influenced modern literature, music and art.

He was known to have been a libertine and a restless soul, traveling extensively on three continents before his death from cancer less

than a month after his 37th birthday.

Arthur Rimbaud was born into the provincial middle class of Charleville (now part of Charleville - Mézières) in the Ardennes département

in

northeastern France. He was the second child of a career soldier,

Frédéric Rimbaud, and his wife Marie - Catherine - Vitalie

Cuif.

His father, a Burgundian of Provençal extraction, rose from a simple recruit to the rank of captain, and spent the greater part of his army

years in foreign service.

Captain Rimbaud fought in the conquest of Algeria and was awarded the Légion d'honneur.

The Cuif family was a

solidly established Ardennais family, but they

were plagued by unstable and bohemian characters; two of Arthur

Rimbaud's uncles from

his mother's side were alcoholics.

Captain

Rimbaud and Vitalie married in February 1853; in the following November

came the birth of their first child, Jean - Nicolas -

Frederick. The next

year, on 20 October 1854, Jean - Nicolas - Arthur was born. Three more

children, Victorine (who died a month after

she was born), Vitalie and

Isabelle, followed. Arthur Rimbaud's infancy is said to have been

prodigious; a common myth states that soon

after his birth he had

rolled onto the floor from a cushion where his nurse had put him only

to begin crawling toward the door. In a more

realistic retelling of his childhood, Mme Rimbaud recalled when after putting her second son in the care of a nurse in Gespunsart,

supplying clean linen and a cradle for him, she returned to find the

nurse's child sitting in the crib wearing the clothes meant for Arthur.

Meanwhile, the dirty and naked child that was her own was happily

playing in an old salt chest.

Soon after the birth of Isabelle, when Arthur was six years old, Captain Rimbaud left to join his regiment in Cambrai and never returned.

He

had become irritated by domesticity and the presence of the children

while Madame Rimbaud was determined to rear and educate her

family by

herself. The young Arthur Rimbaud was therefore under the complete governance of his mother, a strict Catholic,

who raised him

and his older brother and younger sisters in a stern and

religious household. After her husband's departure, Mme Rimbaud became

known as "Widow Rimbaud".

Fearing

that her children were spending too much time with and being

over-influenced by neighbouring children of the poor, Mme Rimbaud

moved

her family to the Cours d'Orléans in 1862.

This

was a better neighborhood, and whereas the boys were previously taught

at home

by their mother, they were then sent, at the ages of nine and

eight, to the Pension Rossat. For the five years that they attended

school,

however, their formidable mother still imposed her will upon

them, pushing for scholastic success. She would punish her sons by

making

them learn a hundred lines of Latin verse by heart and if they

gave an inaccurate recitation, she would deprive them of meals. When Arthur was nine, he wrote a 700-word essay objecting to his having to learn Latin in

school. Vigorously condemning a classical education as a mere gateway

to a salaried position, Rimbaud wrote repeatedly, "I will be a rentier

(one who lives off his assets)".

He

disliked schoolwork and his mother's continued control and constant

supervision; the children were not allowed to leave their mother's

sight, and, until the boys were sixteen and fifteen respectively, she

would walk them home from the school grounds.

loveliest eyes I've seen". When he was eleven, Arthur had his First Communion; despite his intellectual and individualistic nature, he was an ardent Catholic like his mother. For this reason he was called "sale petit Cagot" ("snotty little prig") by his fellow schoolboys. He and his brother were sent to the Collège de Charleville for school that same year. Until this time, his reading was confined almost entirely to the Bible, but he also enjoyed fairy tales and stories of adventure such as the novels of James Fenimore Cooper and Gustave Aimard. He became a highly successful student and was head of his class in all subjects but sciences and mathematics. Many of his schoolmasters remarked upon the young student's ability to absorb great quantities of material. In 1869 he won eight first prizes in the school, including the prize for Religious Education, and in 1870 he won seven firsts.

When

he had reached the third class, Mme Rimbaud, hoping for a brilliant

scholastic future for her second son, hired a tutor, Father

Ariste

Lhéritier, for private lessons.

Lhéritier

succeeded in sparking the young scholar's love of Greek and Latin as

well as French

classical literature. He was also the first person to

encourage the boy to write original verse in both French and Latin. Rimbaud's

first

poem to appear in print was "Les Etrennes des orphelins" ("The

Orphans' New Year's Gift"), which was published in the 2 January

1870

issue of Revue pour tous.

Two weeks after his poem was printed, a new teacher named Georges Izambard arrived

at the Collège de Charleville. Izambard became Rimbaud's

literary mentor and soon a close accord formed between professor and

student and Rimbaud for a short time saw Izambard as a kind of older

brother figure. At

the age of fifteen, Rimbaud was showing maturity as a poet; the first

poem he showed Izambard, "Ophélie", would later be included in

anthologies as one of Rimbaud's three or four best poems.

When the Franco - Prussian War broke

out, Izambard left Charleville and Rimbaud became despondent. He ran

away to Paris with no money for his ticket and was subsequently

arrested and imprisoned for a week. After returning home, Rimbaud ran

away to escape his mother's wrath.

From late October 1870, Rimbaud's behaviour became outwardly provocative; he drank alcohol, spoke rudely, composed scatological poems, stole books from local shops, and abandoned his hitherto characteristically neat appearance by allowing his hair to grow long. At the same time he wrote to Izambard about his method for attaining poetical transcendence or visionary power through a "long, intimidating, immense and rational derangement of all the senses. The sufferings are enormous, but one must be strong, be born a poet, and I have recognized myself as a poet." It is rumoured that he briefly joined the Paris Commune of 1871, which he portrayed in his poem L'orgie parisienne (ou : Paris se repeuple), ("The Parisian Orgy" or "Paris Repopulates"). Another poem, Le cœur volé ("The Stolen Heart"), is often interpreted as a description of him being raped by drunken Communard soldiers, but this is unlikely since Rimbaud continued to support the Communards and wrote poems sympathetic to their aims.

Rimbaud was encouraged by friend and office employee Charles Auguste Bretagne to write to Paul Verlaine, an eminent Symbolist poet, after letters to other poets failed to garner replies. Taking his advice, Rimbaud sent Verlaine two letters containing several of his poems, including the hypnotic, gradually shocking "Le Dormeur du Val" (The Sleeper in the Valley), in which certain facets of Nature are depicted and called upon to comfort an apparently sleeping soldier. Verlaine, who was intrigued by Rimbaud, sent a reply that stated, "Come, dear great soul. We await you; we desire you" along with a one-way ticket to Paris. Rimbaud arrived in late September 1871 at Verlaine's invitation and resided briefly in Verlaine's home. Verlaine, who was married to the seventeen year old and pregnant Mathilde Mauté, had recently left his job and taken up drinking. In later published recollections of his first sight of Rimbaud, Verlaine described him at the age of seventeen as having "the real head of a child, chubby and fresh, on a big, bony rather clumsy body of a still growing adolescent, and whose voice, with a very strong Ardennes accent, that was almost a dialect, had highs and lows as if it were breaking."

Rimbaud and Verlaine began a short and torrid affair. Whereas Verlaine had likely engaged in prior homosexual experiences,

it

remains uncertain whether the relationship with Verlaine was

Rimbaud's first. During their time together they led a wild,

vagabond like life spiced by absinthe and hashish.

They scandalized the Parisian literary coterie on account of the outrageous behaviour of Rimbaud, the archetypical enfant terrible, who throughout this period continued to write strikingly visionary verse. The stormy relationship between Rimbaud and Verlaine eventually brought them to London in September 1872,

a

period about which Rimbaud would later express regret. During this

time, Verlaine abandoned his wife and infant son (both of whom he had

abused in his alcoholic rages). Rimbaud and Verlaine lived in

considerable poverty, in Bloomsbury and in Camden Town, scraping a living mostly from teaching, in addition to an allowance from Verlaine's mother. Rimbaud spent his days in the Reading Room of the British Museum where "heating, lighting, pens and ink were free." The relationship between the two poets grew increasingly bitter.

By

late June 1873, Verlaine grew frustrated with the relationship and

returned to Paris, where he quickly began to mourn Rimbaud's

absence.

On 8 July, he telegraphed Rimbaud, instructing him to come to the Hotel

Liège in Brussels; Rimbaud complied at once.

The

Brussels reunion went badly: they argued continuously and Verlaine took refuge in heavy drinking.

On the morning of 10 July, Verlaine

bought a revolver and ammunition. That

afternoon, "in a drunken rage," Verlaine fired two shots at Rimbaud,

one of them wounding the 18

year old in the left wrist. Rimbaud

dismissed the wound as superficial, and did not initially seek to file

charges against Verlaine. But shortly after the shooting, Verlaine (and

his mother) accompanied Rimbaud to a Brussels railway

station, where Verlaine "behaved as if he were insane." His bizarre

behavior induced Rimbaud to "fear that he might give himself over to

new excesses," so he turned and ran away. In his words, "it was then I [Rimbaud] begged a police officer to arrest him [Verlaine]."

Verlaine was arrested for attempted murder and subjected to a humiliating medico - legal examination.

He

was also interrogated with regard to both his intimate correspondence

with Rimbaud and his wife's accusations about the nature of his

relationship with Rimbaud. Rimbaud eventually withdrew the complaint, but the judge nonetheless sentenced Verlaine to two years in prison.

Rimbaud returned home to Charleville and completed his prose work Une Saison en Enfer ("A

Season in Hell") – still widely regarded as

one of the pioneering

examples of modern Symbolist writing — which made various allusions to

his life with Verlaine, described as a drôle

de ménage ("domestic farce") with his frère pitoyable ("pitiful brother") and vierge folle ("mad virgin") to whom he was l'époux infernal ("the

infernal groom"). In 1874 he returned to London with the poet Germain Nouveau

and put together his groundbreaking Illuminations.

Rimbaud and Verlaine met for the last time in March 1875, in Stuttgart, Germany, after Verlaine's release from prison and his conversion to Catholicism. By then Rimbaud had given up writing and decided on a steady, working life; some speculate he was fed up with his former wild living, while others suggest he sought to become rich and independent to afford living one day as a carefree poet and man of letters. He continued to travel extensively in Europe, mostly on foot.

In May 1876 he enlisted as a soldier in the Dutch Colonial Army

to travel free of charge to Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia)

where he promptly deserted, returning to France by ship.

At the official residence of the mayor of Salatiga, a small city 46 km south of

Semarang, capital of Central Java Province, there is a marble plaque stating that Rimbaud was once settled at the city.

In December 1878, Rimbaud arrived in Larnaca, Cyprus, where he worked for a construction company as a foreman at a stone quarry. In

May of the following year he had to leave Cyprus because of a fever, which on his return to France was diagnosed as typhoid.

In 1880 Rimbaud finally settled in Aden, Yemen as a main employee in the Bardey agency. He took several native women as lovers and

for a while he lived with an Ethiopian mistress. In 1884 he left his job at Bardey's to become a merchant on his own account in Harar,

Ethiopia.

Rimbaud's commercial dealings notably included coffee and weapons. In

this period, Rimbaud struck up a very close friendship

with the

Governor of Harar, Ras Makonnen, father of future Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie.

In February 1891, Rimbaud developed what he initially thought was arthritis in his right knee. It

failed to respond to treatment and became

agonisingly painful, and by

March the state of his health forced him to prepare to return to France

for treatment.

In Aden, Rimbaud

consulted a British doctor who mistakenly diagnosed tubercular synovitis and recommended immediate amputation.

Rimbaud delayed

until 9 May to set his financial affairs in order before catching the boat back to France. On arrival, he was admitted to hospital in Marseille,

where his right leg was amputated on 27 May. The post-operative diagnosis was cancer. After

a short stay at his family home in Charleville, he attempted to travel

back to Africa, but on the way his health deteriorated and he was

readmitted to the same hospital in Marseille where his surgery had been

carried out, and spent some time there in great pain, attended by his

sister Isabelle. Rimbaud died in Marseille on 10 November 1891, at the

age of 37, and he was interred in Charleville.

In May 1871, Rimbaud wrote the celebrated letter commonly called the Lettre du voyant ("Letter of the Seer"). Written before his first trip to Paris, the letter expounded his revolutionary theories about poetry and life, while also denouncing most poets that preceded him. Wishing for new poetic forms and ideas, he wrote:

Rimbaud's poetry influenced the Symbolists, Dadaists and Surrealists, and later writers adopted not only some of his themes, but also his inventive use of form and language. French poet Paul Valéry stated that "all known literature is written in the language of common sense — except Rimbaud's."I say it is necessary to be a voyant, make oneself a voyant. The Poet makes himself a voyant by a long, immense and rational derangement of all the senses. All the forms of love, suffering, and madness. He searches himself. He exhausts all poisons in himself and keeps only their quintessences. He is responsible for humanity, for animals even. He will have to make his inventions smelt, touched, and heard. A language must be found. Moreover, every word [utterance] being an idea, the time of a Universal Language will come!