<Back to Index>

- Economist Hermann Heinrich Gossen, 1810

- Singer and Composer Joseph Legros, 1739

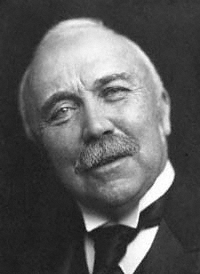

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Henry Campbell Bannerman, 1836

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, GCB (7 September 1836 – 22 April 1908) was a British Liberal Party statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908. No previous First Lord of the Treasury had been officially called "Prime Minister"; this term only came into official usage 5 days after he took office.

Known as CB, he was a firm believer in free trade, Irish Home Rule and the improvement of social conditions: he has been called "Britain's first and only radical prime minister". Campbell-Bannerman led the Liberal Party to a landslide victory over the Conservative Party at the 1906 general election.

The government he led introduced legislation to ensure trade unions

could not be liable for damages incurred during strike action and to

provide free school meals for children.

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836 – 1908) was born at Kelvinside House in Glasgow, Scotland as Henry Campbell, the second son and youngest of the six children born to Sir James Campbell of Stracathro (1790 – 1876) and his wife Janet Bannerman (d. 1873). Sir James Campbell had started work at a young age in the clothing trade in Glasgow, before going into partnership with his brother in 1817 to found J.& W. Campbell & Co., a warehousing, general wholesale and retail drapery business. Sir James was elected as a member of Glasgow Town Council in 1831 and stood as a Conservative candidate for Glasgow constituency in the 1837 and 1841 general elections, before serving as Lord Provost of Glasgow from 1840 to 1843. Henry's older brother, James, was the Conservative Member of Parliament for Glasgow and Aberdeen Universities from 1880 to 1906. In 1871 Henry Campbell became Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the addition of the surname Bannerman being a requirement of the will of his uncle, Henry Bannerman, from whom he inherited the estate of Hunton Court in Kent.

Campbell-Bannerman was educated at the High School of Glasgow (1845 – 1847), the University of Glasgow (1851), and Trinity College, Cambridge (1854 – 1858), where he achieved a Third-Class Degree in Classical Tripos. After graduating, he joined the family firm of J.& W. Campbell & Co., based in Glasgow’s Ingram Street. Campbell was made a partner in the firm in 1860. Following his marriage that year to Sarah Charlotte Bruce, Henry and his new bride set up residence at 6 Claremont Gardens in the Park district in the West End of Glasgow. The couple had no children.

Campbell-Bannerman spoke French, German and Italian, and every summer he and his wife spent a couple of months in Europe, usually in France and at the spa town of Marienbad in Bohemia.

In April 1868, at the age of thirty-one, Campbell-Bannerman stood as a Liberal candidate in a by-election for the Stirling Burghs constituency, narrowly losing to fellow Liberal John Ramsay. However, at the general election in November of that year, Campbell - Bannerman defeated Ramsay and was elected to the House of Commons as Liberal Member of Parliament for Stirling Burghs — a constituency he was to represent for almost forty years.

Campbell-Bannerman was appointed as Financial Secretary to the War Office in Gladstone's First government in November 1871, serving in this position until 1874, and held it again from 1880 to 1882 in Gladstone's Second government. After serving as Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to the Admiralty between 1882 and 1884, Campbell-Bannerman entered Gladstone's cabinet as Chief Secretary for Ireland in 1884.

In Gladstone's Third (1886) and Fourth (1892 – 1894) governments and Rosebery's Government (1894 – 1895) he served as Secretary of State for War, where he persuaded the Duke of Cambridge, the Queen's cousin, to resign as Commander-in-Chief. This earned Campbell - Bannerman a knighthood.

In 1898 Campbell-Bannerman succeeded Sir William Vernon Harcourt as leader of the Liberals in the House of Commons. The Boer War (1899 – 1902) split the Liberal party into Imperialist and Pro-Boer camps and Campbell - Bannerman had a difficult time in holding together the strongly divided party, which was defeated in the "khaki election" of 1900. However the Liberal Party was able to unite in its opposition to the Education Act 1902 and the Brussels Sugar Convention of 1902, in which Britain and nine other nations attempted to stabilise world sugar prices by setting up a commission to investigate export bounties and decide on penalties. The Conservative government had threatened countervailing duties and subsidies of West Indian sugar producers as a negotiating tool. The Convention would phase out export bounties and Britain would forbid the importation of subsidised sugar. In a speech to the Cobden Club on 28 November 1902 Campbell - Bannerman denounced the Convention as threatening the sovereignty of Britain:

It means that we abandon our fiscal independence, together with our free - trade ways; that we subside into the tenth part of a Vehmgericht which is to direct us what sugar is to be countervailed, at what rate per cent we are to countervail it, how much is to be put on for the bounty, and how much for the tariff being in excess of the convention tariff; and this being the established order of things, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer in his robes obeys the orders that he receives from this foreign convention, in which the Britisher is only one out of ten, and the House of Commons humbly submits to the whole transaction. ("Shame.") Sir, of all the insane schemes ever offered to a free country as a boon this is surely the maddest.

However it was Joseph Chamberlain's proposals for Tariff Reform (protectionism) in May 1903 which provided the Liberals with a great cause on which to campaign. Chamberlain's proposals dominated politics through the rest of 1903 up until the general election of 1906. Campbell - Bannerman, like other Liberals, held an unshakable belief in free trade. He proclaimed: "...to dispute Free Trade, after fifty years' experience of it, is like disputing the law of gravitation". On another occasion he explained the Liberals' support for free trade:

We are satisfied that it is right because it gives the freest play to individual energy and initiative and character and the largest liberty both to producer and consumer. ... trade is injured when it is not allowed to follow its natural course, and when it is either hampered or diverted by artificial obstacles. ... We believe in free trade because we believe in the capacity of our countrymen. That at least is why I oppose protection root and branch, veiled and unveiled, one-sided or reciprocal. I oppose it in any form. Besides we have experience of fifty years, during which our prosperity has become the envy of the world.

In 1903 the Liberal Party's chief whip negotiated a pact with Ramsay MacDonald of the Labour Representation Committee to withdraw Liberal candidates in order to help LRC candidates in certain seats. Campbell - Bannerman got on well with Labour leaders and he said in 1903: "We are keenly in sympathy with the representatives of Labour. We have too few of them in the House of Commons". However he was not a socialist. One biographer has written: "He was deeply and genuinely concerned about the plight of the poor and so had readily adopted the rhetoric of progressivism, but he was not a progressive".

The Liberals returned to power in December 1905 when Arthur Balfour resigned as Prime Minister, leaving Campbell - Bannerman to form a minority government. He faced down the Relugas Compact between Asquith, Grey and Haldane, who wanted him to be a weakened Prime Minister from the House of Lords.

Campbell - Bannerman immediately dissolved Parliament and called a general election. In his first speech as premier on 21 December 1905, Campbell - Bannerman launched the Liberal election campaign, focusing on the traditional Liberal platform of "peace, retrenchment and reform":

Expenditure calls for taxes, and taxes are the plaything of the tariff reformer. Militarism, extravagance, protection are weeds which grow in the same field, and if you want to clear the field for honest cultivation you must root them all out. For my own part, I do not believe that we should have been confronted by the spectre of protection if it had not been for the South African war. ... Depend upon it that in fighting for our open ports and for the cheap food and material upon which the welfare of the people and the prosperity of our commerce depend we are fighting against those powers, privileges, injustices, and monopolies which are unalterably opposed to the triumph of democratic principles.

The Liberals swept to power in a landslide victory. Henry Campbell - Bannerman was the first man to be given official use of the title ‘Prime Minister’.

On 23 July 1906 Campbell-Bannerman delivered a speech in French to a conference of the Inter-Parliamentary Union at Westminster. Just before he gave his speech, Campbell - Bannerman received the news that the Russian Duma had been dissolved. He therefore included in his speech: "La Douma est morte – Vive la Douma" [The Duma is dead; long live the Duma].

In that 1907, Campbell - Bannerman achieved the honour of becoming the Father of the House,

the only serving British Prime Minister to do so to date. Nevertheless

his health soon took a turn for the worse, and he resigned as Prime

Minister on 3 April 1908, to be succeeded by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Herbert Henry Asquith. Campbell - Bannerman remained in residence at 10 Downing Street in

the immediate aftermath of his resignation, and became the only

(former) Prime Minister to die there, on 22 April 1908. His last words

were "This is not the end of me". Campbell - Bannerman was buried in the churchyard of Meigle Parish Church, Perthshire, near Belmont Castle, his home since 1887. A relatively modest stone plaque set in the exterior wall of the church serves as a memorial.

Campbell-Bannerman's premiership saw the Entente with Russia in 1907, brought about principally by the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey.

In January 1906 Grey sanctioned staff talks between Britain and France's army and navy but without any binding commitment. These included the plan to send one hundred thousand British soldiers to France within two weeks of a Franco - German war. Campbell - Bannerman was not informed of these at first but when Grey told him about them he gave them his blessing. This was the origin of the British Expeditionary Force that would be sent to France in 1914 at the start of the Great War with Germany. Campbell - Bannerman did not inform the rest of the Cabinet of these staff talks because there was no binding commitment and because he wanted to preserve the unity of the government. The radical members of the Cabinet such as Lord Loreburn, Lord Morley and Lord Bryce would have opposed such cooperation with the French.

Campbell - Bannerman visited France in April 1907 and met the French Radical Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau. Clemenceau believed that the British would help France in a war with Germany but Campbell - Bannerman told him Britain was in no way committed. He may have been unaware that the staff talks were still ongoing. Not long after this Violet Cecil met Clemeanceau and she wrote down what he had said to her about the meeting:

Clemenceau said... ‘I am totally opposed to you – we both recognise a great danger and you are... reducing your army and weakening your navy.’ ‘Ah’ said Bannerman ‘but that is for economy!’... [Clemenceau] then said that he thought the English ought to have some kind of military service, at which Bannerman nearly fainted... ‘It comes to this’ said Clemenceau ‘in the event of your supporting us against Germany are you ready to abide by the plans agreed upon between our War Offices and to land 110,000 men on the coast while Italy marches with us in the ranks?’ Then came the crowning touch of the interview. ‘The sentiments of the English people would be totally averse to any troops being landed by England on the continent under any circumstances.’ Clemenceau looks upon this as undoing the whole result of the entente cordiale and says that if that represents the final mind of the British Government, he has done with us.

Campbell - Bannerman's

biographer John Wilson has described the meeting as "a clash between

two fundamentally different philosophies". The Liberal journalist and friend of Campbell - Bannerman, F.W. Hirst,

claimed that Campbell - Bannerman "had not a ghost of a notion that the

French Entente was being converted into a... return to the old balance of power which

had involved Great Britain in so many wars on the Continent.

That... Grey and Haldane did not inform the Cabinet is astonishing; that

a true hearted apostle of peace like Sir Henry Campbell - Bannerman

should have known of

the danger and yet concealed it from his colleagues is incredible, and

I am happy to conclude... with an assurance that in the days of his

triumph the Liberal leader, having fought a good fight, kept the faith

to the end and was in no way responsible for the European tragedy that

came to pass six years after his death".

Campbell - Bannerman's government granted the Boer states, the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony, self-government within the British Empire through an Order-in-Council so as to bypass the House of Lords. This led to the Union of South Africa in 1910.

The first South African Prime Minister, General Louis Botha,

believed that "Campbell - Bannerman's act [in giving self-government

back to the Boers] had redressed the balance of the Anglo - Boer War,

or had,

at any rate, given full power to the South Africans themselves to

redress it". The former Boer general, Jan Smuts, wrote to David Lloyd George in

1919: "My experience in South Africa has made me a firm believer in

political magnanimity, and your and Campbell - Bannerman's great record

still remains not only the noblest but also the most successful page in recent British statesmanship". However the Unionist politician Lord Milner opposed it, saying in August 1907: "People here – not only Liberals – seem

delighted, and to think themselves wonderfully fine fellows for having

given South Africa back to the Boers. I think it all sheer lunacy".

On the day of Campbell - Bannerman's death the flag of the National Liberal Club was lowered to half-mast, the blinds were drawn and his portrait was draped in black as a sign of mourning. John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Nationalist Party, paid tribute to Campbell - Bannerman by saying that "We all feel that Ireland has lost a brave and considerate friend". David Lloyd George said on hearing of Campbell - Bannerman's death:

I think it will be felt by the community as a whole as if they had lost a relative. Certainly those who have been associated with him closely for years will feel a deep sense of personal bereavement. I have never met a great public figure since I have been in politics who so completely won the attachment and affection of the men who came into contact with him. He was not merely admired and respected; he was absolutely loved by us all. I really cannot trust myself to say more. The masses of the people of this country, especially the more unfortunate of them, have lost the best friend they ever had in the high places of the land. His sympathy in all suffering was real, deep, and unaffected. He was truly a great man — a great head and a great heart. He was absolutely the bravest man I ever met in politics. He was entirely free from fear. He was a man of supreme courage. Ireland has certainly lost one of her truest friends, and what is true of Ireland is true of every section of the community of this Empire which has a fight to maintain against powerful foes.

In an uncharacteristically emotional speech on 27 April, the day of Campbell - Bannerman's funeral, his successor Herbert Henry Asquith told the House of Commons:

What was the secret of the hold which in these later days he unquestionably had on the admiration and affection of men of all parties and all creeds? ...he was singularly sensitive to human suffering and wrong doing, delicate and even tender in his sympathies, always disposed to despise victories won in any sphere by mere brute force, an almost passionate lover of peace. And yet we have not seen in our time a man of greater courage — courage not of the defiant or aggressive type, but calm, patient, persistent, indomitable... In politics I think he may be fairly described as an idealist in aim, and an optimist by temperament. Great causes appealed to him. He was not ashamed, even on the verge of old age, to see visions and to dream dreams. He had no misgivings as to the future of democracy. He had a single minded and unquenchable faith in the unceasing progress and the growing unity of mankind... He never put himself forward, yet no one had greater tenacity of purpose. He was the least cynical of mankind, but no one had a keener eye for the humours and ironies of the political situation. He was a strenuous and uncompromising fighter, a strong Party man, but he harboured no resentments, and was generous to a fault in appreciation of the work of others, whether friends or foes. He met both good and evil fortune with the same unclouded brow, the same unruffled temper, the same unshakable confidence in the justice and righteousness of his cause... He has gone to his rest, and to-day in this House, of which he was the senior and the most honoured Member, we may call a truce in the strife of parties, while we remember together our common loss, and pay our united homage to a gracious and cherished memory—

How happy is he born and taught

That serveth not another's will;

Whose armour is his honest thought,

And simple truth his utmost skill;

This man is freed from servile bands

Of hope to rise or fear to fall;

Lord of himself, though not of lands,

And, having nothing, yet hath all.

Robert Smillie, the trade unionist and Labour MP, said that, after Gladstone, Campbell - Bannerman was the greatest man he had ever met.

George Dangerfield said Campbell - Bannerman's death "was like the passing of true Liberalism. Sir Henry had believed in Peace, Retrenchment, and Reform, those amiable deities who presided so complacently over large portions of the Victorian era... And now almost the last true worshipper at those large, equivocal altars lay dead". Campbell - Bannerman held firmly to the Liberal principles of Richard Cobden and William Ewart Gladstone. It was not until Campbell - Bannerman's departure that the doctrines of New Liberalism came to be implemented. Friedrich Hayek said: "Perhaps the government of H. Campbell - Bannerman... should be regarded as the last liberal government of the old type, while under his successor, H.H. Asquith, new experiments in social policy were undertaken which were only doubtfully compatible with the older liberal principles".

There is a blue plaque outside Campbell - Bannerman's house at 6 Grosvenor Place, London SW1. On 6 December 2008 former Liberal Democrat leaders Charles Kennedy and David Steel, now Lord Steel of Aikwood, unveiled a plaque to commemorate Sir Henry at the home in Bath Street, Glasgow. Lord Steel praised his predecessor as Liberal Party leader as an "overlooked radical" whose 1906 landslide victory had paved the way for a succession of reforming governments. "He led the way for the longest period of successful radical government ever, which was continued by Herbert Asquith and David Lloyd George," Lord Steel said.

His bronze bust, sculpted by Paul Raphael Montford is in Westminster Abbey (1908).