<Back to Index>

- Historian Francisco Javier Clavijero Echegaray, 1731

- Poet Clemens Brentano, 1778

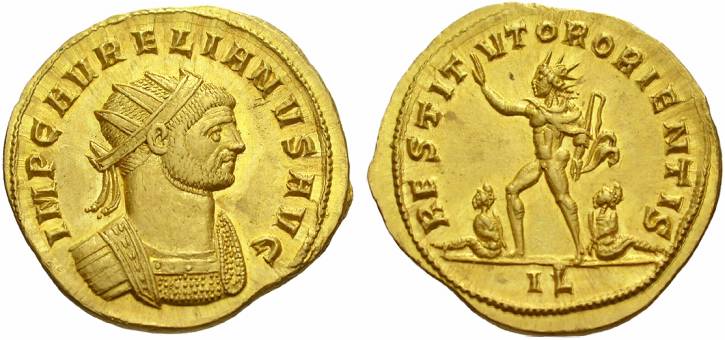

- Emperor of the Roman Empire Lucius Domitius Aurelianus, 214

PAGE SPONSOR

Lucius Domitius Aurelianus (9 September 214 or 215 – September or October 275), commonly known as Aurelian, was Roman Emperor from 270 to 275. During his reign, he defeated the Alamanni after a devastating war, as well as the Goths and Vandals. Aurelian restored the empire's eastern provinces after his conquest of the Palmyrene Empire in 273. The following year he conquered the Gallic Empire in the west, reuniting the empire in its entirety. He was also responsible for the construction of the Aurelian Walls in Rome, and the abandonment of the province of Dacia. His successes effectually ended the empire's Crisis of the Third Century.

Aurelian was born near Serdica or Sirmium in Moesia or what was later called Dacia Ripensis to an obscure provincial family; his father was tenant to a senator named Aurelius, who gave his name to the family. Aurelian probably joined the army in 235 at around age twenty. He distinguished himself in several wars during the tumultuous mid-century; his successes as a cavalry commander ultimately made him a member of emperor Gallienus' entourage. In 268, Aurelian and his cavalry participated in general Claudius' victory over the Goths at the Battle of Naissus. Later that year Gallienus traveled to Italy and fought Aureolus, his former general and now usurper for the throne. Driving Aureolus back into Mediolanum, Gallienus promptly besieged his adversary in the city. However, while the siege was ongoing the emperor was assassinated. One source says Aurelian, who was present at the siege, participated and supported general Claudius for the purple - which is plausible.

Aurelian was married to Ulpia Severina, about whom little is known. Like Aurelian she may have been from Dacia. They are known to have had a daughter together.

Claudius

was acclaimed emperor by the soldiers outside Mediolanum. The new

emperor immediately ordered the senate to deify Gallienus. Next,

he began to distance himself from those responsible for his

predecessors assassination, ordering the execution of those directly

involved. Aureolus

was still besieged in Mediolanum and sought reconciliation with the new

emperor, but Claudius had no sympathy for a potential rival. The

emperor had Aureolus killed and once source implicates Aurelian in the

deed. During

the reign of Claudius, Aurelian was promoted rapidly: he was given

command of the elite Dalmatian cavalry, and was soon promoted to

overall commander of the cavalry - the emperors position before his

acclamation. The war against Aureolus and the concentration of forces in Italy allowed the Alamanni to break through the Rhaetian limes along the upper Danube. Marching through Raetia and the Alps unhindered, they entered northern Italy and began pillaging the area. In early 269

emperor Claudius and Aurelian marched north to meet the Alamanni,

defeating them decisively at the Battle of Lake Benacus. While still dealing with the defeated enemy, news came from the Balkans reporting large scale attacks from the Heruli, Goths, Gepids, and Bastarnae. Claudius

immediately dispatched Aurelian to the Balkans to contain the invasion

as best he could until Claudius could arrive with his main army. The Goths were besieging Thessalonica when

they heard of emperor Claudius' approach, causing them to abandon the

siege and pillage north eastern Macedonia. Aurelian intercepted the

Goths with his Dalmatian cavalry and defeated them in a series of minor

skirmishes, killing as many as three thousand of the enemy. Aurelian continued to harass the enemy, driving them northward into Upper Moesia where

emperor Claudius had assembled his main army. The ensuing battle was

indecisive: the northward advance of the Goths was halted but Roman

losses were heavy. Claudius

could not afford another pitched battle, so he instead laid a

successful ambush, killing thousands. However, the majority of the

Goths escaped and began retreating south they way they had come. For

the rest of year Aurelian harassed the enemy with his Dalmatian cavalry. Now

stranded in Roman territory, the Goths lack of provisions began to take

its toll. Aurelian, sensing his enemies desperation attacked them with

the full force of his cavalry, killing many and driving the remainder westward into Thrace. As winter set in, the Goths retreated into the Haemus Mountains only

to find themselves trapped and surrounded. The harsh conditions now

exacerbated their shortage of food. However, the Romans underestimated

the Goths and let their guard down, allowing the enemy to break through

their lines and escape. Apparently emperor Claudius ignored advice,

perhaps from Aurelian, and withheld the cavalry and sent in only the

infantry to stop their break-out. The determined Goths killed many of

the oncoming infantry and were only prevented from slaughtering them

all when Aurelian finally charged in with his Dalmatian cavalry. The

Goths still managed to escape and continued their march through Thrace. The

Roman army continued to follow the Goths during the spring and summer

of 270. Meanwhile, a devastating plague swept through the Balkans,

killing many soldiers in both armies. Emperor Claudius fell ill and

returned to his regional headquarters in Sirmium, leaving Aurelian in

charge of operations against the Goths. Aurelian used his cavalry to great effect, breaking the Goths into smaller

groups which were easier to deal with. By late summer the Goths were

defeated: any survivors were stripped of their animals and booty and

were levied into the army or settled as farmers in frontier regions. Aurelian had no time to relish his victories, in late August news arrived from Sirmium that emperor Claudius was dead. When Claudius died, his brother Quintillus seized power with support of the Senate. With an act typical of the Crisis of the Third Century, the army refused to recognize the new emperor, preferring to support

one of its own commanders: Aurelian was proclaimed emperor in September

270 by the legions in

Sirmium. Aurelian defeated Quintillus' troops, and was recognized

emperor by the Senate after Quintillus' death. The claim that Aurelian

was chosen by Claudius on his death bed can be dismissed as propaganda; later, probably in 272, Aurelian put his own dies imperii the day of Claudius' death, thus implicitly considering Quintillus a usurper. With

his base of power secure, he now turned his attention to Rome's

greatest problems — recovering the vast territories lost over the

previous two decades, and reforming the res publica.

In 248, Emperor Philip the Arab had

celebrated the millennium of the city of Rome with great and expensive

ceremonies and games, and the empire had given a tremendous proof of

self-confidence. In the following years, however, the empire had to

face a huge pressure from external enemies, while, at the same time,

dangerous civil wars threatened the empire from within, with usurpers

weakening the strength of the state. Also, the economical substrate of

the state, the agriculture and the commerce, suffered from the

disruption caused by the instability. On top of this an epidemic swept

through the Empire around 250, greatly diminishing manpower both for

the army and for agriculture. The end result was that the empire could

not endure the blow of the capture of Emperor Valerian in 260. The eastern provinces found their protectors in the rulers of the city of Palmyra, in Syria, whose autonomy grew until the formation of the Palmyrene Empire, which was more successful against the Persian threat. The western provinces, those facing the limes of the Rhine seceded, forming a third, autonomous state within the territories of the Roman Empire, which is now known as Gallic Empire. In Rome, the emperor was occupied with the internal menaces to his power and with the defence of Italia and

the Balkans. This was the situation faced by Gallienus and Claudius,

and the problems Aurelian had to deal with at the beginning of his rule.

The

first actions of the new emperor were aimed at strengthening his own

position in his territories. Late in 270, Aurelian campaigned in

northern Italia against the Vandals, Juthungi, and Sarmatians, expelling them from Roman territory. To celebrate these victories, Aurelian was granted the title of Germanicus Maximus. The authority of the emperor was challenged by several usurpers — Septimius, Urbanus, Domitianus, and the rebellion of Felicissimus —

who tried to exploit the sense of insecurity of the empire and the

overwhelming influence of the armies in Roman politics. Aurelian, being

an experienced commander, was aware of the importance of the army, and

his propaganda, known through his coinage, shows he wanted the support

of the legions.

The burden of the northern barbarians was not yet over, however. In 271, the Alamanni moved towards Italia, entering the Po plain and sacking the villages; they passed the Po River, occupied Placentia and moved towards Fano. Aurelian, who was in Pannonia to control Vandals' withdrawal, quickly entered Italia, but his army was defeated in an ambush near Placentia (January

271). When the news of the defeat arrived in Rome, it caused great fear

for the arrival of the barbarians. But Aurelian attacked the Alamanni

camping near the Metaurus River, defeating them in the Battle of Fano, and forcing them to re-cross the Po river; Aurelian finally routed them at Pavia. For this, he received the title Germanicus Maximus.

However, the menace of the German people remained high as perceived by

the Romans, so Aurelian resolved to build the walls that became known

as the Aurelian Walls around Rome.

The emperor led his legions to the Balkans, where he defeated and routed the Goths beyond the Danube, killing the Gothic leader Cannabaudes, and assuming the title of Gothicus Maximus. However, he decided to abandon the province of Dacia,

on the exposed north bank of the Danube, as too difficult and expensive

to defend. He reorganised a new province of Dacia south of the Danube,

inside the former Moesia, called Dacia Aureliana, with Serdica as the capital. In 272, Aurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire, the so-called "Palmyrene Empire" ruled by Queen Zenobia from the city of Palmyra. Zenobia had carved out her own empire, encompassing Syria, Palestine, Egypt and large parts of Asia Minor. In the beginning, Aurelian had been recognized as emperor, while Vaballathus, the son of Zenobia, hold the title of rex and imperator ("king"

and "supreme military commander"), but Aurelian decided to invade the

eastern provinces as soon as he felt his army to be strong enough. Asia Minor was recovered easily; every city but Byzantium and Tyana surrendered

to him with little resistance. The fall of Tyana lent itself to a

legend: Aurelian to that point had destroyed every city that resisted

him, but he spared Tyana after having a vision of the great 1st century

philosopher Apollonius of Tyana,

whom he respected greatly, in a dream. Apollonius implored him,

stating, "Aurelian, if you desire to rule, abstain from the blood of

the innocent! Aurelian, if you will conquer, be merciful!" Whatever the

reason, Aurelian spared Tyana. It paid off; many more cities submitted

to him upon seeing that the emperor would not exact revenge upon them.

Within six months, his armies stood at the gates of Palmyra, which

surrendered when Zenobia tried to flee to the Sassanid Empire.

The "Palmyrene Empire" was no more. Eventually Zenobia and her son were

captured and made to walk on the streets of Rome in his triumph. After

a brief clash with the Persians and another in Egypt against usurper Firmus,

Aurelian was obliged to return to Palmyra in 273 when that city

rebelled once more. This time, Aurelian allowed his soldiers to sack

the city, and Palmyra never recovered. More honors came his way; he was

now known as Parthicus Maximus and Restitutor Orientis ("Restorer of the East"). The

rich province Egypt was also recovered by Aurelian. The Brucheion

(Royal Quarter) in Alexandria was burned to the ground. This section of

the city once contained the Library of Alexandria,

although it is not known if the Library still existed in Aurelian's

time. (It had already been damaged by fire during the visit of Julius Caesar to Alexandria.) In 274, the victorious emperor turned his attention to the west, and the "Gallic Empire"

which had already been reduced in size by Claudius II. Aurelian won

this campaign largely through diplomacy; the "Gallic Emperor" Tetricus was

willing to abandon his throne and allow Gaul and Britain to return to

the empire, but could not openly submit to Aurelian. Instead, the two

seem to have conspired so that when the armies met at Châlons-en-Champagne that

autumn, Tetricus simply deserted to the Roman camp and Aurelian easily

defeated the Gallic army facing him. Tetricus was rewarded for his part

in the conspiracy with a high ranking position in Italy itself. Aurelian returned to Rome and won his last honorific from the Senate – Restitutor Orbis ("Restorer

of the World"). In four years, he had secured the frontiers of the

empire and reunified it, effectively giving the empire a new lease on

life that lasted 200 years.

Aurelian was a reformer, and settled many important functions of the imperial

apparatus, including the economy and the religion. He also restored

many public buildings, re-organized the management of the food

reserves, set fixed prices for the most important goods, and prosecuted

misconduct by the public officers.

Aurelian strengthened the position of the Sun god, Sol (Invictus)

or Oriens, as the main divinity of the Roman pantheon. His intention

was to give to all the peoples of the Empire, civilian or soldiers,

easterners or westerners, a single god they could believe in without

betraying their own gods. The center of the cult was a new temple,

built in 271 in Campus Agrippae in

Rome, with great decorations financed by the spoils of the Palmyrene

Empire. Aurelian did not persecute other religions. However, during his

short rule, he seemed to follow the principle of "one god, one empire",

that was later adopted to a full extent by Constantine. On some coins, he appears with the title deus et dominus natus ("God and born ruler"), also later adopted by Diocletian. Lactantius argued that Aurelian would have outlawed all the other gods if he had had enough time. Aurelian's reign records the only uprising of mint workers. The rationalis Felicissimus,

mintmaster at Rome, revolted against Aurelian. The revolt seems to have

been caused by the fact that the mint workers, and Felicissimus first,

were accustomed to stealing the silver for the coins and producing

coins of inferior quality. Aurelian wanted to eliminate this, and put

Felicissimus under trial. The rationalis incited the mintworkers to revolt: the rebellion spread in the streets, even if

it seems that Felicissimus was killed immediately, possibly executed. The Palmyrene rebellion in Egypt had probably reduced the grain supply to Rome,

thus disaffecting the population with respect to the emperor. This

rebellion also had the support of some senators, probably those who had

supported the election of Quintillus, and thus had something to fear from Aurelian. Aurelian ordered the

urban cohorts, reinforced by some regular troops of the imperial army,

to attack the rebelling mob: the resulting battle, fought on the Caelian hill,

marked the end of the revolt, even if at a high price (some sources

give the figure, probably exaggerated, of 7,000 casualties). Many of

the rebels were executed; also some of the rebelling senators were put

to death. The mint of Rome was closed temporarily, and the institution

of several other mints caused the main mint of the empire to lose its

hegemony. His monetary reformation included in the introduction of antoninianii containing 5% silver. They bore the mark XXI (or its Greek numerals form KA), which meant that twenty of such coins would contain the same silver quantity of an old silver denarius. Considering

that this was an improvement over the previous situation gives an idea

of the severity of the economic situation Aurelian faced. The emperor

struggled to introduce the new "good" coin by recalling all the old

"bad" coins prior to their introduction. In 275, Aurelian marched towards Asia Minor, preparing another campaign against the Sassanids: the deaths of Kings Shapur I (272) and Hormizd I (273) in quick succession, and the rise to power of a weakened ruler (Bahram I), set the possibility to attack the Sassanid Empire. On

his way, the emperor suppressed a revolt in Gaul — possibly against

Faustinus, an officer or usurper of Tetricus — and defeated barbarian

marauders in Vindelicia (Germany). However,

Aurelian never reached Persia, as he was murdered while waiting in

Thrace to cross into Asia Minor. As an administrator, Aurelian had been

very strict and handed out severe punishments to corrupt officials or

soldiers. A secretary of Aurelian (called Eros by Zosimus) had told a lie on a minor issue. In fear of what the emperor might do,

he forged a document listing the names of high officials marked by the

emperor for execution, and showed it to collaborators. The notarius Mucapor and other high ranking officers of the Praetorian Guard, fearing punishment from the Emperor, murdered him in September of 275, in Caenophrurium, Thrace (modern Turkey). Aurelian's enemies in the Senate briefly succeeded in passing damnatio memoriae on the emperor, but this was reversed before the end of the year and Aurelian, like his predecessor Claudius II, was deified as Divus Aurelianus. There is substantial evidence that Aurelian's wife Ulpia Severina, who had been declared Augusta in 274, may have ruled the Empire by her own power for some time after his death. The sources indicate that there was an interregnum between Aurelian's death and the election of Marcus Claudius Tacitus as his successor. Additionally, some of Ulpia's coins appear to have been minted after Aurelian's death.

Aurelian's

short reign reunited a fragmented Empire while saving Rome from

barbarian invasions that had reached Italy itself. His death prevented

a full restoration of political stability and a lasting dynasty that

could end the cycle of assassination of Emperors and civil war that

marked this period. Even so, he brought the Empire through a very

critical period in its history and without Aurelian, it would never

have survived the invasions and fragmentation of the decade in which he

reigned. 20 years later the reign of Diocletian would fully restore stability and end the Crisis of the third century. The Western half would survive another 200 years while the East would thrive for another millennium.