<Back to Index>

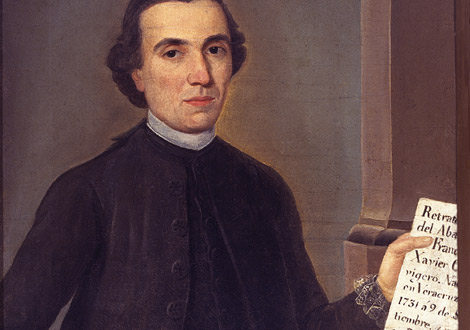

- Historian Francisco Javier Clavijero Echegaray, 1731

- Poet Clemens Brentano, 1778

- Emperor of the Roman Empire Lucius Domitius Aurelianus, 214

PAGE SPONSOR

Francisco Javier Clavijero Echegaray (sometimes Francesco Saverio Clavigero) (September 9, 1731 – April 2, 1787), was a Novohispano Jesuit teacher, scholar and historian. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spanish colonies (1767), he went to Italy, where he wrote a valuable work on the pre-Columbian history and civilizations of Mesoamerica and the central Mexican altiplano.

He was born in Veracruz (Mexico) of a Spanish father and a Criolla mother. His father worked for the Spanish crown, and was transferred with his family from one town to another. Most of the father's posts were to locations with a strong indigenous presence, and because of this Clavijero learned Nahuatl growing up. The family lived at various times in Teziutlán, Puebla and later in Jamiltepec, in the Mixtec region of Oaxaca. Clavijero's biographer, Juan Luis Maneiro, wrote:

From the time of his boyhood, he had occasion to deal intimately with the indigenous people, to learn thoroughly their customs and nature, and to investigate attentively the many special things the land produces, be they plants, animals or minerals. There was no high mountain, dark cave, pleasant valley, spring, brook, or any other place that drew his curiosity to which the Indians did not take the boy to in order to please him.

He began his studies in Puebla, at the college of San Jerónimo for grammar, and the Jesuit college of San Ignacio for philosophy, Latin and theology. Upon completion of these studies, he entered a seminary in Puebla, Puebla, to study for the priesthood, but he soon decided to become a Jesuit instead. In February 1748 he transferred to a Jesuit college in Tepoztlán, Morelos. There he continued to study Latin and also learned ancient Greek, French, Portuguese, Italian, German, and English.

In 1751 he was sent back to Puebla for further studies in philosophy.

Here he was introduced to the works of such contemporary thinkers as Descartes, Newton, and Leibniz. Next he was sent to Mexico City, to complete his theological and philosophical studies at the Colegio de San Pedro y Pablo. Here he joined with other students of stature, including José Rafael Campoy, Andrés Cavo, Francisco Javier Alegre, Juan Luis Maneiro and Pedro José Márquez, a group known today (along with others) as the "Mexican humanists of

the eighteenth century". While still a student, he began teaching, and

was made prefect of the Colegio de San Ildefonso. Later he was

appointed to the chair of rhetoric in the Seminario Mayor of the

Jesuits, an exceptional appointment as he had yet to be ordained as a priest. In 1754, Clavijero was ordained a priest. He began to teach at the Colegio de San Gregorio,

founded at the beginning of the colonial era to teach Indian youth. He

spent five years there. Again, quoting from his biographer, Juan Luis

Maneiro: In

those five years he examined with great curiosity all the documents

relating to the Mexican nation that had been collected in large numbers

in the Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo, and with great determination

extracted from them precious treasures that later were published in the

history he left for posterity. Nevertheless,

his time at San Gregorio was not without problems. In a letter dated

April 3, 1761, Father Pedro Reales, vicar general of the Jesuits,

rebuked him in a letter for having

completely shaken off the yoke of obedience, responding with an "I

don't want to" to those who assigned you duties, as occurred yesterday,

or at the very least this answer was given to the superior, who in

truth did not know what path to take so that Your Reverence would

fulfill and embrace your duty. Relocating you is hardly a solution, and

Your Reverence's life and example have provided no satisfaction, almost

completely removing the unique purpose of those who live in this

college, and handing over to others jobs and studies that you fill. It

seems clear that these "other jobs and studies" of Father Clavijero

referred to the Aztec codices and the books of the period of the

Conquest that had been given to the college of San Pedro and San Pablo

by Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora.

Clavijero followed Sigüenza as an example in his investigations,

and was very pleased with Sigüenza's benevolence to and love of

the Indians. He also admired much of the culture of the Indians before

their contact with Europeans. Clavijero never ceased to try to read the

ideograms in the codices. Clavijero was transferred to the Colegio de San Javier in Puebla,

also dedicated to the education of Indian youth. He taught there for

three years. In 1764 he was transferred again, to Valladolid (now Morelia),

to teach philosophy in the seminary there. More of a rationalist in

philosophy than his predecessors, he was an innovator in the field.

Good work in Valladolid got him promoted to the same position in Guadalajara. It was in Guadalajara that he finished his treatise Physica Particularis, which, together with Cursus Philosophicus, sets out his scientific and philosophical thought.

The Jesuits were expelled from all the Spanish dominations on June 25, 1767, on orders of King Charles III. When Clavijero left the colony, he went first to Ferrara, Italy, but soon relocated to Bologna, Italy, where he lived the rest of his life. In

Italy he devoted his time to his historical investigations. Although he

no longer had access to the Aztec codices, the reference works, and the

accounts of the first Spanish conquistadors, he retained in his memory

the information from his earlier studies. He was able to write the work

he had always intended, La Historia Antigua de México. In Italy a work by the Prussian Cornelius Paw came to his attention. It was entitled Philosophical Investigations Concerning the Americans.

This work revealed to Clavijero the extent of European ignorance about

the nature and culture of pre-Columbian Americans, and spurred his work

to show the true history of Mexico. He

worked for years on his history, consulting Italian libraries and

corresponding with friends in Mexico who answered his questions by

consulting the original works there. Finally his work was ready. It

consisted of ten volumes containing the narrative of Mexican culture

from before the Spanish conquest. The original manuscript was in

Spanish, but Father Clavijero translated it into Italian, with the help

of some of his Italian friends. The book was published at Cesena in

1780 - 81, and was received by scholars with great satisfaction. It was

soon translated into English and German. It was also translated back

into Spanish, and went through numerous editions in Mexico. Much later

(1945) the original was published in Spanish. La Historia Antigua de México begins with a description of Anáhuac,

and continues with the story of the Aztec wanderings. It treats of the

politics, warfare, religion, customs, social organization and culture

of the Aztecs. It establishes for the first time the chronology of the

Indian peoples, and concludes with the history of the Conquest up to

the imprisonment of Cuauhtémoc. In

contrast to many of his contemporaries, Clavigero promoted a view of

the Indigenous as peaceful and good, while heavily criticizing the

actions of the Spanish conquistadors.

Clavigero's work is seen today as overly sentimental and unreliable,

but it is still read by many historians who seek detailed information

about early American daily life. In addition to La Historia Antigua de México, Father Clavijero published these works: Father

Francisco Javier Clavijero died in Bologna April 2, 1787, at 4 in the

afternoon. He was 56 years of age. He did not live to see the

publication of Historia de la Antigua o Baja California. On

August 5, 1970, the remains of Father Clavijero were repatriated to

Veracruz, the place of his birth. They were received with the honors

due to an illustrious son. He is now interred in the Rotonda de los Personajes Ilustres in the Pantheon Dolores in Mexico City. Schools, libraries, botanical gardens, avenues and parks throughout the Republic of Mexico have been named for him, including: