<Back to Index>

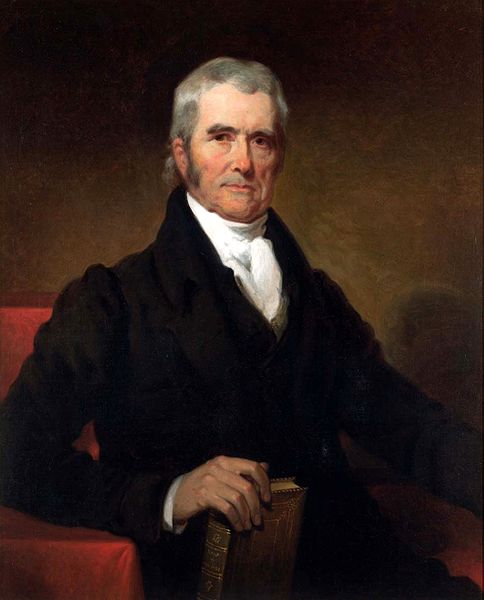

- 4th Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall, 1755

- Writer Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford, 1717

- Supreme Commander of the Armies of the Holy Roman Empire Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein, 1583

PAGE SPONSOR

John Marshall (September 24, 1755 – July 6, 1835) was the Chief Justice of the United States (1801 - 1835) whose court opinions helped lay the basis for American constitutional law while promoting nationalism and making the Supreme Court of the United States a center of power with the capability of overruling Congress. Previously, Marshall had been a leader of the Federalist Party in Virginia and served in the United States House of Representatives from 1799 to 1800. He was Secretary of State under President John Adams from 1800 to 1801.

The longest serving Chief

Justice of the United States, Marshall dominated the Court for over

three decades and played a significant role in the development of the

American legal system. Most notably, he reinforced the principle that

federal courts are obligated to exercise judicial review, by disregarding purported laws if they violate the Constitution.

Thus, Marshall cemented the position of the American judiciary as an

independent and influential branch of government. Furthermore, the

Marshall Court made several important decisions relating to federalism,

affecting the balance of power between the federal government and the

states during the early years of the republic. In particular, he

repeatedly confirmed the supremacy of federal law over state law, and

supported an expansive reading of the enumerated powers. Some

of his decisions were unpopular. Nevertheless, Marshall built up the

third branch of the federal government, and augmented federal power in

the name of the Constitution, and the rule of law. Marshall, along with Daniel Webster (who

argued some of the cases), was the leading Federalist of the day,

pursuing Federalist Party approaches to build a stronger federal

government over the opposition of the Jeffersonian Republicans, who

wanted stronger state governments. John Marshall was born in a log cabin close to Germantown, a rural community on the Virginia frontier, in what is now Fauquier County near Midland, Virginia, on September 24, 1755, to Thomas Marshall and Mary Isham Keith, the granddaughter of Thomas Randolph of Tuckahoe. The

oldest of fifteen, John had eight sisters and six brothers. Also,

several cousins were raised with the family. He was also relative of Thomas Jefferson, both of them being descendants of Virginia colonist William Randolph, though Marshall and Jefferson would oppose each other on many political issues. From

a young age, he was noted for his good humor and black eyes, which were

"strong and penetrating, beaming with intelligence and good nature". Thomas Marshall was employed by Lord Fairfax.

Known as "the Proprietor", Fairfax provided Thomas Marshall with a

substantial income as his lordship’s agent in Fauquier County.

Marshall’s task was to survey the tract, assist in finding people to

settle and collect rents. In

the early 1760s, the Marshall family left Germantown and moved some

thirty miles to Leeds Manor (so named by Lord Fairfax) on the eastern

slope of the Blue Ridge.

On the banks of Goose Creek, Thomas Marshall built a simple wooden

cabin there, much like the one abandoned in Germantown with two rooms

on the first floor and a two - room loft above. Thomas Marshall was not

yet well established, so he leased it from Colonel Richard Henry Lee.

The Marshalls called their new home "the Hollow", and the ten years

they resided there were John Marshall's formative years. In 1773, the

Marshall family moved once again. Thomas Marshall, by then a man of

more substantial means, purchased a 1,700 - acre (6.9 km2)

estate adjacent to North Cobbler Mountain, approximately ten miles

northwest of the Hollow. The new farm was located adjacent to the main

stage road (now U.S. 17) between Salem (the modern day village of Marshall, Virginia) and Delaplane, Virginia.

When John was seventeen, Thomas Marshall built "Oak Hill" there, a

seven - room frame home with four rooms on the first floor and three

above. Although modest in comparison to the estates of George Washington, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson, it

was a substantial home for the period. John Marshall became the owner

of Oak Hill in 1785 when his father moved to Kentucky. Although John

Marshall lived his later life in Richmond, Virginia, and Washington D.C., he kept his Fauquier County property, making improvements and using it as a retreat until his death. Marshall's

early education was superintended by his father who gave him an early

taste for history and poetry. Thomas Marshall's employer, Lord Fairfax,

allowed access to his home at Greenway Court,

which was an exceptional center of learning and culture. Marshall took

advantage of the resources at Greenway Court and borrowed freely from

the extensive collection of classical and contemporary literature.

There were no schools in the region at the time, so home schooling was

pursued. Although books were a rarity for most in the territory, Thomas

Marshall's library was exceptional. His collection of literature, some

of which was borrowed from Lord Fairfax, was relatively substantial and

included works by the ancient Roman historian Livy, the ancient Roman poet Horace, and the English writers Alexander Pope, John Dryden, John Milton, and William Shakespeare.

All of the Marshall children were accomplished, literate, and

self - educated under their parents' supervision. At the age of twelve

John had transcribed Alexander Pope's An Essay on Man and some of his Moral Essays. There

being no formal school in Fauqueir County at the time, John was sent,

at age fourteen, about one hundred miles from home to an academy in

Washington parish. Among his classmates was James Monroe,

the future president. John remained at the academy one year, after

which he was brought home. Afterward, Thomas Marshall arranged for a

minister to be sent who could double as a teacher for the local

children. The Reverend James Thomson, a recently ordained deacon from Glasgow, Scotland,

resided with the Marshall family and tutored the children in Latin in

return for his room and board. When Thomson left at the end of the

year, John had begun reading and transcribing Horace and Livy. The Marshalls had long before decided that John was to be a lawyer. William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England had been published in America and Thomas Marshall bought a copy for his own

use and for John to read and study. After John returned home from

Campbell's academy he continued his studies with no other aid than his

dictionary. John's father superintended the English part of his

education. Marshall wrote of his father, "... and to his care I am

indebted for anything valuable which I may have acquired in my youth.

He was my only intelligent companion; and was both a watchful parent

and an affectionate friend". Marshall served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and was friends with George Washington. He served first as a Lieutenant in the Culpeper Minutemen from

1775 to 1776, and went on to serve as a Lieutenant and then a Captain

in the Eleventh Virginia Continental Regiment from 1776 to 1780. During his time in the army, he enjoyed running races with the other soldiers and was nicknamed "Silverheels" for the white heels his mother had sewn into his stockings. Marshall endured the brutal winter conditions at Valley Forge (1777 – 1778). After his time in the Army, he read law under the famous Chancellor George Wythe in Williamsburg, Virginia, at the College of William and Mary, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and was admitted to the Bar in 1780. He was in private practice in Fauquier County, Virginia, before entering politics. In 1782, Marshall won a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, in which he served until 1789 and again from 1795 to 1796. The Virginia General Assembly elected

him to serve on the Council of State later in the same year. In 1785,

Marshall took up the additional office of Recorder of the Richmond City Hustings Court. In 1788, Marshall was selected as a delegate to the Virginia convention responsible for ratifying or rejecting the United States Constitution, which had been proposed by the Philadelphia Convention a year earlier. Together with James Madison and Edmund Randolph, Marshall led the fight for ratification. He was especially active in

defense of Article III, which provides for the Federal judiciary. His

most prominent opponent at the ratification convention was Anti-Federalist leader Patrick Henry. Ultimately, the convention approved the Constitution by a vote of 89 - 79. Marshall identified with the new Federalist Party (which supported a strong national government and commercial interests), and opposed Jefferson's Democratic - Republican Party (which advocated states' rights and idealized the yeoman farmer and the French Revolution). Meanwhile, Marshall's private law practice continued to flourish. He successfully represented the heirs of Lord Fairfax in Hite v. Fairfax (1786), an important Virginia Supreme Court case involving a large tract of land in the Northern Neck of Virginia. In 1796, he appeared before the United States Supreme Court in another important case, Ware v. Hylton, a

case involving the validity of a Virginia law providing for the

confiscation of debts owed to British subjects. Marshall argued that

the law was a legitimate exercise of the state's power; however, the

Supreme Court ruled against him, holding that the Treaty of Paris in combination with the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution required the collection of such debts. Henry Flanders in his biography of Marshall remarked that Marshall's argument in Ware v. Hylton "elicited

great admiration at the time of its delivery, and enlarged the circle

of his reputation." Flanders also wrote that the reader "cannot fail to

be impressed with the vigor, rigorous analysis, and close reasoning

that mark every sentence of it." In 1795, Marshall declined Washington's offer of Attorney General of the United States and, in 1796, declined to serve as minister to France. In 1797, he accepted when President John Adams appointed

him to a three - member commission to represent the United States in

France. (The other members of this commission were Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry.)

However, when the envoys arrived, the French refused to conduct

diplomatic negotiations unless the United States paid enormous bribes.

This diplomatic scandal became known as the XYZ Affair, inflaming anti - French opinion in the United States. Hostility increased even further when the Directoire expelled

Marshall and Pinckney from France. Marshall's handling of the affair,

as well as public resentment toward the French, made him popular with

the American public when he returned to the United States. In 1798, Marshall declined a Supreme Court appointment, recommending Bushrod Washington, who would later become one of Marshall's staunchest allies on the Court. In 1799, Marshall reluctantly ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. Although his congressional district (which included the city of Richmond) favored the Democratic - Republican Party, Marshall won the race, in part due to his conduct during the XYZ Affair and in part due to the support of Patrick Henry.

His most notable speech was related to the case of Thomas Nash (alias

Jonathan Robbins), whom the government had extradited to Great Britain

on charges of murder. Marshall defended the government's actions,

arguing that nothing in the Constitution prevents the United States

from extraditing one of its citizens. On May 7, 1799, President Adams nominated Congressman Marshall as Secretary of War. However, on May 12, Adams withdrew the nomination, instead naming him Secretary of State, as a replacement for Timothy Pickering. Confirmed by the United States Senate on May 13, Marshall took office on June 6, 1800. As Secretary of State, Marshall directed the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which ended the Quasi - War with France and brought peace to the new nation. Marshall served as Chief Justice during all or part of the administrations of six Presidents: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. He remained a stalwart advocate of Federalism and a nemesis of the Jeffersonian school of government throughout its heyday. He participated in over 1000 decisions, writing 519 of the opinions himself. He

helped to establish the Supreme Court as the final authority on the

meaning of the Constitution in cases and controversies that must be

decided by the federal courts. His impact on constitutional law is without peer, and his imprint on the Court's jurisprudence remains indelible.

Marshall was thrust into the office of Chief Justice in the wake of the presidential election of 1800.

With the Federalists soundly defeated and about to lose both the

executive and legislative branches to Jefferson and the

Democratic - Republicans, President Adams and the lame duck Congress passed what came to be known as the Midnight Judges Act,

which made sweeping changes to the federal judiciary, including a

reduction in the number of Justices from six to five so as to deny

Jefferson an appointment until two vacancies occurred. As the incumbent Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth was in poor health, Adams first offered the seat to ex-Chief Justice John Jay, who declined on the grounds that the Court lacked "energy, weight, and dignity." Jay's

letter arrived on January 20, 1801, and as there was precious little

time left, Adams nominated Marshall, who was with him at the time and

able to accept immediately. The Senate at first delayed, hoping that

Adams would make a different choice, such as promoting Justice William Paterson of New Jersey. According to New Jersey Senator Jonathan Dayton,

the Senate finally relented "lest another not so qualified, and more

disgusting to the Bench, should be substituted, and because it appeared

that this gentleman [Marshall] was not privy to his own nomination". Marshall

was confirmed by the Senate on January 27, 1801, and received his

commission on January 31, 1801. While Marshall officially took office

on February 4, at the request of the President he continued to serve as

Secretary of State until Adams' term expired on March 4. President

John Adams offered this appraisal of Marshall's impact: "My gift of

John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act

of my life."

Soon

after becoming Chief Justice, Marshall changed the manner in which the

Supreme Court announced its decisions. Previously, each Justice would

author a separate opinion (known as a seriatim opinion) as is still done in the 20th and 21st centuries in such jurisdictions as the United Kingdom and Australia.

Under Marshall, however, the Supreme Court adopted the practice of

handing down a single opinion of the Court, allowing it to present a

clear rule. As Marshall was almost always the author of this opinion, he essentially became the Court's sole mouthpiece in important cases. Marshall's

forceful personality allowed him to steer his fellow Justices; only

once did he find himself on the losing side in a constitutional case. In that case (Ogden v. Saunders in 1827), Marshall set forth his general principles of constitutional interpretation: Marshall

was in the dissenting minority only eight times throughout his tenure

at the Court, partly because of his influence over the associate justices. As Oliver Wolcott observed

when both he and Marshall served in the Adams administration, Marshall

had the knack of "putting his own ideas into the minds of others,

unconsciously to them". However, he regularly curbed his own viewpoints, preferring to arrive at decisions by consensus. He adjusted his role to accommodate other members of the court as they developed. Marshall

had charm, humor, a quick intelligence, and the ability to bring men

together. His sincerity and presence commanded attention. His opinions

were workmanlike but not especially eloquent or subtle. His influence

on learned men of the law came from the charismatic force of his

personality, and his ability to seize upon the key elements of a case

and make highly persuasive arguments. Together with his vision of the

future greatness of the nation, these qualities are apparent in his

historic decisions and gave him the sobriquet, The Great Chief Justice. Marshall

ran a congenial court; there was seldom any bickering. The Court met in

Washington only two months a year, from the first Monday in February

through the second or third week in March. Six months of the year the

justices were doing circuit duty in

the various states. Marshall was therefore based in Richmond, his

hometown, for most of the year. When the Court was in session in

Washington, the justices boarded together in the same rooming house,

avoided outside socializing, and discussed each case intently among

themselves. Decisions were quickly made usually in a matter of days.

Marshall wrote nearly half the decisions during his 33 years in office.

Lawyers appearing before the court, including the most brilliant in the

United States, typically gave oral arguments and

often did not present written briefs. The justices did not have clerks,

so they listened closely to the oral arguments, and decided among

themselves what the decision should be. The court issued only one

decision; the occasional dissenter usually did not issue a separate

opinion. While

Marshall was very good at listening to the oral briefs, and convincing

the other justices of his interpretation of the law, he was not widely

read in the law, and seldom cited precedents. After the Court came to a

decision, he would usually write it up himself. Often he asked Justice Story,

a renowned legal scholar, to do the chores of locating the precedents,

saying, "There, Story; that is the law of this case; now go and find

the authorities." The three previous chief justices (John Jay, John Rutledge, and Oliver Ellsworth)

had left little permanent mark beyond setting up the forms of office.

The Supreme Court, like many state supreme courts, was a minor organ of

government. In his 34 - year tenure, Marshall gave it the energy, weight,

and dignity of a third co-equal branch. With his associate justices,

especially Joseph Story, William Johnson, and Bushrod Washington, Marshall's Court brought to life the constitutional standards of the new nation. Marshall

used Federalist approaches to build a strong federal government over

the opposition of the Jeffersonian Democrats, who wanted stronger state

governments. His

influential rulings reshaped American government, making the Supreme

Court the final arbiter of constitutional interpretation. The Marshall

Court struck down an act of Congress in only one case (Marbury v. Madison in

1803) but that established the Court as a center of power that could

overrule the Congress, the president, the states, and all lower courts

if that is what a fair reading of the Constitution requires. He also

defended the legal rights of corporations by tying them to the

individual rights of the stockholders, thereby ensuring that

corporations have the same level of protection for their property as

individuals had, and shielding corporations against intrusive state

governments. Marbury v. Madison (1803) was the first important case before Marshall's Court. In that case, the Supreme Court invalidated a provision of the Judiciary Act of 1789 on the grounds that it violated the Constitution by attempting to expand the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. Marbury was

the first and only case in which the Marshall Court ruled an act of

Congress unconstitutional, and thereby reinforced the doctrine of judicial review.

Thus, although the Court indicated that the Jefferson administration

was violating another law, the Court said it could not do anything

about it due to its own lack of jurisdiction. President Thomas Jefferson took the position that the Court could not give him a mandamus (i.e. an order) even if the Court had jurisdiction: More

generally, Jefferson lamented that allowing the Constitution to mean

whatever the Court says it means would make the Constitution "a mere

thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and

shape into any form they please." Because Marbury v. Madison decided

that a jurisdictional statute passed by Congress was unconstitutional,

that was technically a victory for the Jefferson administration (so it

could not easily complain). Ironically what was unconstitutional was

Congress' granting a certain power to the Supreme Court itself. The

case allowed Marshall to proclaim the doctrine of judicial review,

which reserves to the Supreme Court final authority to judge whether or

not actions of the president or of the congress are within the powers

granted to them by the Constitution. The Constitution itself is the

supreme law, and when the Court believes that a specific law or action

is in violation of it, the Court must uphold the Constitution and set

aside that other law or action, assuming that a party has standing to properly invoke the Court's jurisdiction. Chief Justice Marshall famously put the matter this way: The Constitution does not explicitly give judicial review to

the Court, and Jefferson was very angry with Marshall's position, for

he wanted the President to decide whether his acts were constitutional

or not. Historians mostly agree that the framers of the Constitution

did plan for the Supreme Court to have some sort of judicial review;

what Marshall did was make operational their goals. Judicial review was not new and Marshall himself mentioned it in the Virginia

ratifying convention of 1788. Marshall's opinion expressed and fixed in

the American tradition and legal system a more basic theory — government

under law. That is, judicial review means a government in which no

person (not even the President) and no institution (not even Congress

or the Supreme Court itself), nor even a majority of voters, may freely

work their will in violation of the written Constitution. Marshall

himself never declared another law of Congress or act of a president

unconstitutional.

The Burr trial (1807) was presided over by Marshall together with Judge Cyrus Griffin. This was the great state trial of former Vice President Aaron Burr, who was charged with treason and high misdemeanor.

Prior to the trial, President Jefferson condemned Burr and strongly

supported conviction. Marshall, however, narrowly construed the

definition of treason provided in Article III of the Constitution; he

noted that the prosecution had failed to prove that Burr had committed

an "overt act,"

as the Constitution required. As a result, the jury acquitted the

defendant, leading to increased animosity between the President and the

Chief Justice. Fletcher v. Peck (1810)

was the first case in which the Supreme Court ruled a state law

unconstitutional, though the Court had long before voided a state law

as conflicting with the combination of the Constitution together with a

treaty (Marshall had represented the losing side in that 1796 case). In Fletcher,

the Georgia legislature had approved a land grant, known as the Yazoo

Land Act of 1795. It was then revealed that the land grant had been

approved in return for bribes, and therefore voters rejected most of

the incumbents; the next legislature repealed the law and voided all

subsequent transactions (even honest ones) that resulted from the Yazoo land scandal.

The Marshall Court held that the state legislature's repeal of the

law was void because the sale was a binding contract, which according

to Article I, Section 10, Clause I (the Contract Clause)

of the Constitution, cannot be invalidated. Marshall emphasized that

the rescinding act would seize property from individuals who had

honestly acquired it, and transfer that property to the public without

any compensation. He then expanded upon his own famous statement

in Marbury about the province of the judiciary: Based on this separation of powers principle, Marshall

questioned whether the rescinding act would be valid even if Georgia

were a completely sovereign state independent of the federal

Constitution. Ultimately, though, Marshall grounded the Court's opinion

in the restrictions imposed by the federal Constitution. As in Marbury, this decision of the Court in Fletcher was unanimous.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

was one of several decisions during the 1810s and 1820s, involving the

balance of power between the federal government and the states, where

he repeatedly affirmed federal supremacy. He established in McCulloch that states could not tax federal institutions, and upheld congressional authority to create the Second Bank of the United States, even though the authority to do this was not expressly stated in the Constitution. As

the young nation was endangered by regional and local interests that

often threatened to fracture its hard - fought unity, Marshall

repeatedly interpreted the Constitution broadly so that the Federal

Government had

the power to become a respected and creative force guiding and

encouraging the nation's growth. Thus, for all practical purposes, the Constitution in

its most important aspects today is the Constitution as John Marshall

interpreted it. As Chief Justice, he embodied the judiciary of the

government as fully as the President of the United States stood for the power of the Executive Branch. McCulloch v. Maryland was Marshall's second greatest single judicial performance. While it was consistent with Marbury v. Madison, it cut the other way by affirming the constitutionality of a federal

statute, while preventing states from passing laws that violate federal

law. The opinion includes the famous statement, "We must never forget

that it is a constitution we are expounding." Marshall laid down the

basic theory of implied powers under a written Constitution; intended,

as he said "to endure for ages to come, and, consequently, to be

adapted to the various crises of human affairs ...." Marshall envisaged

a federal government which, although governed by timeless principles,

possessed the powers "on which the welfare of a nation essentially

depends." It would be free in its choice of means, and open to change

and growth. The

Court held that the bank was authorized by the clause of the

Constitution that says Congress can implement its powers by making laws

that are "necessary and proper", which Marshall said does not refer to one single way that Congress is allowed to act, but rather refers to various possible

acts that implement all constitutionally established powers. Marshall

famously provided the following time - honored interpretation of this

clause in the Constitution: According to the New York Times, "Marshall did not intend his words as license for Congress to do whatever it wishes." Instead,

Marshall and the Court deemed the bank necessary and proper because it

furthered various legitimate ends that are listed in the Constitution, such as regulating interstate commerce. Cohens v. Virginia (1821) displayed Marshall's nationalism as he enforced the supremacy of federal law over state law, under the Supremacy Clause of

the Constitution. In this case, he established that the Federal

judiciary could hear appeals from decisions of state courts in criminal

cases as well as the civil cases over which the court had asserted

jurisdiction in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816). Justices Bushrod Washington and Joseph Story proved to be his strongest allies in these cases. Like Marbury, this Cohens case

was largely about the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. The State of

Virginia claimed that the Court had no jurisdiction to hear appeals

from a state court in a case between a state and its own citizens, even

if the case involved interpretation of a federal statute. Marshall

wrote that his court did have appellate jurisdiction, but then went on to affirm the decision of the Virginia Supreme Court on the merits. Marshall wrote: In Marshall's day, the Court had not yet been given the discretion whether or not to take cases. Scholars such as Edward Hartnett contend that the Court's discretionary certiorari practice undercuts the rationale that Chief Justice Marshall gave in the Cohens case for reviewing the validity of state law, which was that the Court had no choice in the matter. The decision in Cohens demonstrated

that the federal judiciary can act directly on private parties and

state officials, and has the power to declare and impose on the states

the Constitution and federal laws, but Marshall stressed that federal

laws have limits. For example, he said, "Congress has a right to punish

murder in a fort, or other place within its exclusive jurisdiction; but

no general right to punish murder committed within any of the States." In this case, the Court affirmed that the Virginia Supreme Court correctly interpreted a federal statute that had established a lottery in Washington D.C. Like the Jefferson administration in Marbury, the State of Virginia technically won this case even though the case set a precedent consolidating the power of the Court. Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)

overturned a monopoly granted by the New York state legislature to

certain steamships operating between New York and New Jersey. Daniel Webster argued that the Constitution, by empowering Congress to regulate interstate commerce, implied that states do not have any concurrent power to regulate interstate commerce. Chief Justice Marshall avoided that issue about the exclusivity of the federal commerce power because

that issue was not necessary to decide the case. Instead, Marshall

relied on an actual, existing federal statute for licensing ships, and

he held that that federal law was a legitimate exercise of the

congressional power to regulate interstate commerce, so the federal law

superseded the state law granting the monopoly. Webster was at that time a member of Congress, but nevertheless pressed his constitutional views on behalf of clients. After

he won this case, he bragged that Marshall absorbed his arguments "as a

baby takes in his mother's milk", even though Marshall had actually dismissed Webster's main argument. In

the course of his opinion in this case, Marshall began the careful work

of determining what the phrase "commerce... among the several states"

means in the Constitution. He stressed that one must look at whether

the commerce in question has wide ranging effects, suggesting that

commerce which does "affect other states" may be interstate commerce,

even if it does not cross state lines. Of course, the steamboats in

this case did cross a state line, but Marshall suggested that his

opinion had a broader scope than that. Indeed, Marshall's opinion in Gibbons would be cited by the Supreme Court much later when it upheld aspects of the New Deal in cases like Wickard v. Filburn in 1942. But, the opinion in Gibbons can also be read more narrowly. After all, Marshall also wrote: The immediate impact of the historic decision in Gibbons was to end many state granted monopolies. That in turn lowered prices and promoted free enterprise. Marshall wrote several other important Supreme Court opinions, including the following. In Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 518 (1819),

the legal structure of modern corporations began to develop, when the

Court held that private corporate charters are protected from state

interference by the Contract Clause of the Constitution. In Johnson v. M'Intosh, 21 U.S. 543 (1823),

the Court held that private American citizens could not purchase tribal

lands directly from Native Americans (then called "Indians"). Instead,

only the government could do so, and then private citizens could

purchase from the government. In Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832),

a Georgia criminal statute, which prohibited non-Indians from being

present on Indian lands without a license from the state, was held

unconstitutional, because the federal government has exclusive

authority in such matters. It is often said that, in response to the

decision, President Andrew Jackson,

said something to the effect of: "John Marshall has made his decision;

now let him enforce it!" More reputable sources recognize this as a

false quotation. In fact, the ruling in Worcester ordered nothing more than that Worcester be freed; Georgia complied after several months. In Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. 243 (1833),

the Court held that the Bill of Rights was intended to apply only

against the federal government, and therefore does not apply against

the states. The Court has subsequently held that the holding in Barron was altered by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Marshall greatly admired George Washington, and between 1805 and 1807 published an influential five - volume biography. Marshall's Life of Washington was

based on records and papers provided to him by the late president's

family. The first volume was reissued in 1824 separately as A History of the American Colonies. The work reflected Marshall's Federalist principles. His revised and condensed two - volume Life of Washington was published in 1832. Historians

have often praised its accuracy and well - reasoned judgments, while

noting his frequent paraphrases of published sources such as William

Gordon's 1801 history of the Revolution and the British Annual Register. After

completing the revision to his biography of Washington, Marshall

prepared an abridgment. In 1833 he wrote, "I have at length completed

an abridgment of the Life of Washington for the use of schools. I have

endeavored to compress it as much as possible. . . . After striking out

every thing which in my judgment could be properly excluded the volume

will contain at least 400 pages." The Abridgment was not published until 1838, three years after Marshall died. Marshall loved his home, built in 1790, in Richmond, Virginia, and spent as much time there as possible in quiet contentment. While in Richmond he attended St. John's Church in Church Hill until 1814 when he led the movement to hire Robert Mills as architect of Monumental Church,

which commemorated the death of 72 people in a theatre fire. The

Marshall family occupied pew No. 23 at Monumental Church and

entertained the Marquis de Lafayette there during his visit to Richmond in 1824. Marshall was not religious and never joined any church; he did not believe Christ was divine. For

approximately three months each year; however, he would be away in

Washington for the Court's annual term; he would also be away for

several weeks to serve on the circuit court in Raleigh, North Carolina. In 1823, he became first president of the Richmond branch of the American Colonization Society, which was dedicated to resettling freed American slaves in Liberia, on the West coast of Africa. In 1828, he presided over a convention to promote internal improvements in Virginia. In

1829, he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention, where

he was again joined by fellow American statesman and loyal Virginians, James Madison and James Monroe,

although all were quite old by that time. Marshall mainly spoke at this

convention to promote the necessity of an independent judiciary. On

December 25, 1831, Mary, his beloved wife of some 49 years, died. Most

who knew Marshall agreed that after Mary's death, he was never quite

the same. His health, which had not been good for several years,

rapidly declined in 1835, and in June he journeyed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for medical attendance. There he died on July 6, at the age of 79, having served as Chief Justice for over 34 years. Two

days before his death, he enjoined his friends to place only a plain

slab over his and his wife's graves, and he wrote the simple

inscription himself. His body, which was taken to Richmond, lies in Shockoe Hill Cemetery in a well kept grave. JOHN MARSHALL Marshall was the second to last surviving Founding Father, the last being James Madison. Some of the papers of John Marshall are held by the Special Collections Research Center at the College of William & Mary. Marshall's home in Richmond, Virginia, has been preserved by APVA Preservation Virginia. It is considered to be an important landmark and museum, essential to an understanding of the Chief Justice's life and work. The United States Bar Association commissioned sculptor William Wetmore Story to execute the statue of Marshall that now stands inside the Supreme Court on the ground floor. Another

casting of the statue is located at Constitution Ave. and 4th Street in

Washington D.C. and a third on the grounds of the Philadelphia Museum

of Art. Story's father Joseph Story had served as an Associate Justice on the United States Supreme Court with Marshall. The statue was originally dedicated in 1884. An

engraved portrait of Marshall appears on U.S. paper money on the series

1890 and 1891 treasury notes. These rare notes are in great demand by

note collectors today. Also, in 1914, an engraved portrait of Marshall

was used as the central vignette on series 1914 $500 federal reserve

notes. These notes are also quite scarce. (William McKinley replaced

Marshall on the $500 bill in 1928.) Example of both notes are available

for viewing on the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco website. On September 24, 1955, the United States Postal Service issued the 40¢ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring Marshall with a 40 cent stamp. Having

grown from a Reformed Church academy, Marshall College, named upon the

death of Chief Justice John Marshall, officially opened in 1836 with a

well - established reputation. After a merger with Franklin College in

1853, the school was renamed Franklin and Marshall College. The college went on to become one of the nation's foremost liberal arts colleges. Four law schools and one University today bear his name: The Marshall - Wythe School of Law (now William and Mary Law School at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia; The Cleveland - Marshall College of Law in Cleveland, Ohio; John Marshall Law School in Atlanta, Georgia; and, The John Marshall Law School in Chicago, Illinois. The University that bears his name is Marshall University in Huntington West Virginia. Marshall County, Illinois, Marshall County, Indiana, Marshall County, Kentucky, and Marshall County, West Virginia, are also named in his honor. A number of high schools around the nation have also been named for him. John Marshall's birthplace in Fauquier County is a park, the John Marshall Birthplace Park, and a marker can be seen on Route 28 noting this place and event. Marshall, Michigan was named in his honor five years before Marshall's death. It was the first of dozens of communities and counties named for him. John Marshall was an active Freemason and served as Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Marshall was a descendant of the Randolph family of Virginia, including William Randolph I and Thomas Randolph (of Tuckahoe). Other prominent family connections include:

“ To

say that the intention of the instrument must prevail; that this

intention must be collected from its words; that its words are to be

understood in that sense in which they are generally used by those for

whom the instrument was intended; that its provisions are neither to be

restricted into insignificance, nor extended to objects not

comprehended in them, nor contemplated by its framers; -- is to repeat

what has been already said more at large, and is all that can be

necessary. ”

“ In

the case of Marbury and Madison, the federal judges declared that

commissions, signed and sealed by the President, were valid, although

not delivered. I deemed delivery essential to complete a deed, which,

as long as it remains in the hands of the party, is as yet no deed, it

is in posse only, but not in esse,

and I withheld delivery of the commissions. They cannot issue a

mandamus to the President or legislature, or to any of their officers. ” “ It

is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say

what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of

necessity, expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with

each other, the Courts must decide on the operation of each. ”

“ It

is the peculiar province of the legislature to prescribe general rules

for the government of society; the application of those rules to

individuals in society would seem to be the duty of other departments. ”

“ Let

the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution,

and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that

end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit

of the constitution, are constitutional. ”

“ We

have no more right to decline the exercise of jurisdiction which is

given, than to usurp that which is not given. The one or the other

would be treason to the constitution. ”

“ The

enumeration presupposes something not enumerated; and that something,

if we regard the language or the subject of the sentence, must be the

exclusively internal commerce of a state..... Inspection laws,

quarantine laws, health laws of every description, as well as laws for

regulating the internal commerce of a State, and those which respect

turnpike roads, ferries, &c., are.... subject to State legislation.

If the legislative power of the Union can reach them, it must be for

national purposes; it must be where the power is expressly given for a

special purpose, or is clearly incidental to some power which is

expressly given. ”

Son of Thomas and Mary Marshall

was born September 24, 1755

Intermarried with Mary Willis Ambler

the 3rd of January 1783

Departed this life

the 6th day of July 1835.