<Back to Index>

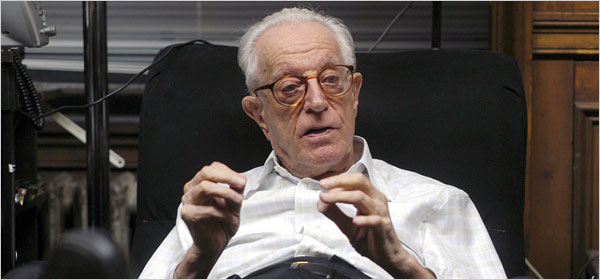

- Psychologist Albert Ellis, 1913

- Painter Frank Handlen, 1916

- 1st Prime Minister of South Africa Louis Botha, 1862

PAGE SPONSOR

Albert Ellis (September 27, 1913 – July 24, 2007) was an American psychologist who in 1955 developed Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT). He held M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in clinical psychology from Columbia University and American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP). He also founded and was the president emeritus of the New York City based Albert Ellis Institute. He is generally considered to be one of the originators of the cognitive revolutionary paradigm shift in psychotherapy and the founder of cognitive - behavioral therapies. Based on a 1982 professional survey of U.S. and Canadian psychologists, he was considered as the second most influential psychotherapist in history (Carl Rogers ranked first in the survey; Sigmund Freud was ranked third). The magazine Psychology Today described him as the “greatest living psychologist.”

Ellis was born to a Jewish family in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1913. He was the eldest of three children. Ellis' father was a businessman, often away from home on business trips, who reportedly showed only a modicum of affection to his children. In his autobiography, Ellis characterized his mother as a self - absorbed woman with a bipolar disorder. At times, according to Ellis, she was a "bustling chatterbox who never listened." She would expound on her strong opinions on most subjects, but rarely provided a factual basis for these views. Like his father, Ellis' mother was emotionally distant from her children. Ellis recounted that she was often sleeping when he left for school and usually not home when he returned. Instead of reporting feeling bitter, he took on the responsibility of caring for his siblings. He purchased an alarm clock with his own money and woke and dressed his younger brother and sister. When the Great Depression struck, all three children sought work to assist the family. Ellis was sickly as a child and suffered numerous health problems through his youth. At the age of five he was hospitalized with a kidney disease. He was also hospitalized with tonsillitis, which led to a severe streptococcal infection requiring emergency surgery. He reported that he had eight hospitalizations between the ages of five and seven, one of which lasted nearly a year. His parents provided little emotional support for him during these years, rarely visiting or consoling him. Ellis stated that he learned to confront his adversities as he had "developed a growing indifference to that dereliction". Illness was to follow Ellis throughout his life; at age 40 he developed diabetes.

Ellis

had exaggerated fears of speaking in public and during his adolescence

he was extremely shy around women. At age 19, already showing signs of

thinking like a cognitive - behavioral therapist, he forced himself to

talk to 100 women in the Bronx Botanical Gardens over

a period of a month. Even though he did not get a date, he reported

that he desensitized himself to his fear of rejection by women. Ellis entered the field of clinical psychology after first earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in business from the City University of New York in 1934. He began a brief career in business, followed by one as a writer. These endeavors took place during the Great Depression that

began in 1929, and Ellis found that business was poor and had no

success in publishing his fiction. Finding that he could write

non-fiction well, Ellis researched and wrote on human sexuality. His lay counseling in this subject convinced him to seek a new career in clinical psychology. In 1942, Ellis began his studies for a Ph.D. in clinical psychology at Teachers College, Columbia University, which trained psychologists mostly in psychoanalysis.

He completed his Master of Arts in clinical psychology from Teachers

College in June 1943, and started a part-time private practice while

still working on his PhD degree – possibly because there was no

licensing of psychologists in New York at that time. Ellis began

publishing articles even before receiving his Ph.D.; in 1946 he wrote a

critique of many widely used pencil - and - paper personality tests. He concluded that only the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory met the standards of a research based instrument. In

1947 he was awarded a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology (doctorate) at

Columbia, and at that time Ellis had come to believe that

psychoanalysis was the deepest and most effective form of therapy. Like

most psychologists of that time, he was interested in the theories of Sigmund Freud. He sought additional training in psychoanalysis and then began to practice classical psychoanalysis. Shortly after receiving his Ph.D. in 1947, Ellis began a personal analysis and program of supervision with Richard Hulbeck (whose own analyst had been Hermann Rorschach, a leading training analyst at the Karen Horney Institute and the developer of the Rorschach inkblot test). At that time he taught at New York University and Rutgers University and held a couple of leading staff positions. At this time Ellis' faith in psychoanalysis was gradually crumbling. Of psychologists, the writings of Karen Horney, Alfred Adler, Erich Fromm and Harry Stack Sullivan would

arguably be some of the greatest influences in Ellis's thinking and

played a role in shaping his psychological models. Ellis credits Alfred Korzybski, his book, Science and Sanity, and general semantics for

starting him on the philosophical path for founding rational therapy.

In addition modern and ancient philosophy and his own experiences

heavily influenced his new theoretical developments to psychotherapy. By

January 1953 his break with psychoanalysis was complete, and he began

calling himself a rational therapist. Ellis was now advocating a new

more active and directive type of psychotherapy. By 1955 he dubbed his

new approach Rational Therapy (RT). In RT, the therapist sought to help

the client understand — and act on the understanding — that his

personal philosophy contained beliefs that contributed to his own

emotional pain. This new approach stressed actively working to change a

client's self-defeating beliefs and behaviours by demonstrating their

irrationality, self - defeatism and rigidity. Ellis believed that through rational analysis and cognitive reconstruction,

people could understand their self - defeatingness in light of their core

irrational beliefs and then develop more rational constructs. In 1954 Ellis began teaching his new techniques to other therapists, and by 1957 he formally set forth the first cognitive behavior therapy by

proposing that therapists help people adjust their thinking and

behavior as the treatment for emotional and behavioural problems. Two

years later Ellis published How to Live with a Neurotic, which elaborated on his new method. In 1960 Ellis presented a paper on his new approach at the American Psychological Association (APA) convention in Chicago. There was mild interest, but few recognized that the paradigm set forth would become the zeitgeist within a generation. At that time the prevailing interest in experimental psychology was behaviorism, while in clinical psychology it was the psychoanalytic schools of notables such as Freud, Jung, Adler, and Perls.

Despite the fact that Ellis' approach emphasized cognitive, emotive,

and behavioral methods, his strong cognitive emphasis provoked the

psychotherapeutic establishment with the possible exception of the

followers of Adler. Consequently, he was often received with

significant hostility at professional conferences and in print. He

regularly held seminars where he would bring a participant up on stage

and treat them. His treatments were famed for often being delivered in

a rough, confrontational style. Despite

the relative slow adoption of his approach in the beginning, Ellis

founded his own institute. The Institute for Rational Living was

founded as a non-profit organization in 1959. By 1968 it was chartered

by the New York State Board of Regents as a training institute and psychological clinic. By the 1960s, Ellis had come to be seen as one of the founders of the American sexual revolution. Especially in his earlier career, he was well known for his work as a sexologist and for his liberal humanistic, and controversial in some camps, opinions on human sexuality. He also worked with noted zoologist and sex researcher Alfred Kinsey and

explored in a number of books and articles the topic of human sexuality

and love. Sex and love relations was something he had a professional

interest in even from the beginning of his career. In 1958 he published his classic book Sex Without Guilt which came to be known for its liberal sexual attitudes. In 1965 Ellis published a book entitled Homosexuality: Its Causes and Cure, which partly saw homosexuality as a pathology and therefore a condition to be cured. In 1973 the American Psychiatric Association reversed

its position on homosexuality by declaring that it was not a mental

disorder and thus not properly subject to cure, and in 1976 Ellis

clarified his earlier views in Sex and the Liberated Man,

expounding that some homosexual disturbed behaviors may be subject to

treatment but, in most cases, that should not be attempted as

homosexuality is not inherently good or evil, except from a religious

viewpoint. Near the end of his

life, he finally updated and re-wrote Sex Without Guilt in 2001 and released as Sex Without Guilt in the Twenty - First Century.

In this book, he expounded and enhanced his humanistic view on sexual

ethics and morality and dedicated a chapter on homosexuality to giving

homosexuals advice and suggestion on how to more greatly enjoy and

enhance their sexual love lives. While preserving some of the ideas

about human sexuality from the original, the revision constituted his

current humanistic opinions and ethical ideals. In his original version of his book Sex Without Guilt,

Ellis expressed the opinion that religious restrictions on sexual

expression are often needless and harmful to emotional health. He also

famously debated religious psychologists, including Orval Hobart Mowrer and Allen Bergin,

over the proposition that religion often contributed to psychological

distress. Because of his forthright espousal of a nontheistic humanism,

he was recognized in 1971 as Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association.

Ellis most recently described himself as a probabilistic atheist,

meaning that while he acknowledged that he could not be completely

certain there is no god, he believed the probability a god exists was

so small that it was not worth his or anyone else's attention. While

Ellis’ personal atheism and humanism remained consistent, his views

about the role of religion in mental health changed over time. In early

comments delivered at conventions and at his institute in New York

City, Ellis overtly and often with characteristically acerbic sarcasm

stated that devout religious beliefs and practices were harmful to

mental health. In The Case Against Religiosity,

a 1980 pamphlet published by his New York institute, he offered an

idiosyncratic definition of religiosity as any devout, dogmatic and

demanding belief. He noted that religious codes and religious

individuals often manifest religiosity, but added that devout,

demanding religiosity is also obvious among many orthodox

psychotherapists and psychoanalysts, devout political believers and

aggressive atheists. Ellis

was careful to state that REBT was independent of his atheism, noting

that many skilled REBT practitioners are religious, including some who

are ordained ministers. In his later days he significantly toned down

his opposition to religion. While Ellis maintained his firm atheistic

stance, proposing that thoughtful, probabilistic atheism was likely the

most emotionally healthy approach to life, he acknowledged and agreed

with survey evidence suggesting that belief in a loving god can also be

psychologically healthy. Based on this later approach to religion, he reformulated his professional and personal view in one of his last books The Road to Tolerance, and he also co-authored a book, Counseling and Psychotherapy with Religious Persons: A Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy Approach, with

two religious psychologists, Stevan Lars Nielsen and W. Brad Johnson,

describing principles for integrating religious material and beliefs

with REBT during treatment of religious clients. While

many of his ideas were criticized during the 1950s and '60s by the

psychotherapeutic establishment, his reputation grew immensely during

the next decades. From the 1960s on, his prominence was steadily

growing as the cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT) were gaining further theoretical and scientific ground. From then, CBT, which was founded by Aaron T. Beck,

the father of cognitive therapy, gradually became one of the most

popular systems of psychotherapy in many countries. In the late 1960s

his institute launched a professional journal, and in the early 70s

established "The Living School" for children between 6 and 13. The

school provided a curriculum that incorporated the principles of

RE(B)T. Despite its relative short life, interest groups generally

expressed satisfaction with its programmer. Ellis had such an impact that in a 1982 survey,

American and Canadian clinical psychologists and counsellors ranked him

ahead of Freud when asked to name the figure who had exerted the

greatest influence on their field. Also, in 1982, a large analysis of

psychology journals published in the US, found that Ellis was the most

cited author after 1957. In 1985, the APA presented Dr. Ellis with its award for "distinguished professional contributions". He

held many important positions in many professional societies including

the Division of Consulting Psychology of the APA, Society for the

Scientific Study of Sexuality, American Association of Marital and

Family Therapy, the American Academy of Psychotherapists and the

American Association of Sex Educators, Counsellors, and Therapists. In

addition Ellis also served as consulting or associate editor of many scientific journals. Many professional societies gave Ellis their highest professional and clinical awards. In

the mid 1990s he finally renamed his psychotherapy and behavior change

system, originally known as Rational Therapy, then Rational - Emotive

Therapy, Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy.

This he did to stress the interrelated importance of cognition, emotion

and behaviour in his therapeutic approach. In 1994 he also updated and

revised his original, 1962 classic book, "Reason and Emotion in

Psychotherapy". Over the next years he continued developing the theory

underlying his system for psychotherapy and behaviour change and in its

practical applications. His

work also extended into areas other than psychology, including

education, politics, business and philosophy. He eventually became a

prominent and confrontational social commenter and public speaker on a

wide array of issues. During his career he publicly debated a vast

amount of people who represented opposing views to his; this included

for example debates with psychologist Nathaniel Branden on Objectivism and psychiatrist Thomas Szasz on the topic of mental illness.

On numerous occasions he further presented inductive critiques on

opposing psychotherapeutic approaches in addition to on several

occasions questioning some of the doctrines in certain dogmatic

religious systems, spiritualism and mysticism. From

1965 on to the end of his life, through four decades, he led his famous

Friday Night Live group seminars of REBT with volunteers from the

audience for gatherings of often hundreds or more. The 1970s found him

introducing his popular "rational humorous songs", which combined

humorous lyrics with a rational and self-helping message set to a

popular tune. Ellis became known and often applauded for “unshamefully”

singing them aloud with his high pitched and nasal voice. In addition

Ellis held workshops and seminars on mental health and psychotherapy

all over the world all up until his 90s. Until

he fell ill at the age of 92 in 2006, Dr. Ellis typically worked at

least 16 hours a day, writing books in longhand on legal tablets,

visiting with clients and teaching. On his 90th birthday in 2003 he

received congratulatory messages from well known public figures such as

then President George W. Bush, New York senators Charles Schumer and Hillary Clinton, former President Bill Clinton, and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and the Dalai Lama, who sent a silk scarf blessed for the occasion. In 2004 Ellis was taken ill with serious intestinal problems, which led to hospitalization and the removal of his large intestine.

He returned to work after a few months of being nursed back to health

by Debbie Joffe, his assistant, who later became his wife. In

2005 he was subjected to removal from all his professional duties and

from the board of his own institute after a dispute over the management

policies of the institute. Ellis was reinstated to the board in January

2006, after winning civil proceedings against the board members who

removed him. On

June 6, 2007, lawyers acting for Albert Ellis filed a suit against the

Albert Ellis Institute in the Supreme Court of the State of New York.

The suit alleges a breach of a long term contract with the AEI and

sought recovery of the 45 East 65th Street property through the

imposition of a constructive trust. Despite

his series of health issues and a profound hearing loss Ellis never

stopped working relentlessly with his professional activities. His

wife, Australian psychologist Debbie Joffe, assisted him in his work.

Then in April 2006, Ellis was hospitalized with pneumonia, and spent more than a year shuttling between hospital and a

rehabilitation facility. He eventually returned to his residence on the

top floor of the Albert Ellis Institute. At

the time of his death on July 24, 2007, Dr. Ellis served as President

Emeritus of the Albert Ellis Institute in New York and had authored and

co-authored more than 80 books and 1200 articles (including eight

hundred scientific papers) during his lifetime. He died from natural

causes, aged 93. During his final years he collaborated with Dr. Mike Abrams on his only college textbook Personality Theories: Critical Perspectives. Ellis' final book was an autobiography entitled "All Out!"

published by Prometheus Books in June 2010. The book was dedicated to

and contributed by his wife Dr Debbie Joffe Ellis to whom, Dr. Albert

Ellis entrusted the legacy of REBT and described her as "The greatest love of my whole life, my whole life". In

eulogy of Albert Ellis, APA past president Frank Farley states,

“Psychology has had a handful of legendary figures who not only command

attention across much of the discipline but also receive high

recognition from the public for their work. Albert Ellis was such a

figure, known inside and outside of psychology for his astounding

originality, his provocative ideas, and his provocative personality. He

bestrode the practice of psychotherapy like a colossus…”