<Back to Index>

- Engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 1806

- Composer Johann Kaspar Kerll, 1627

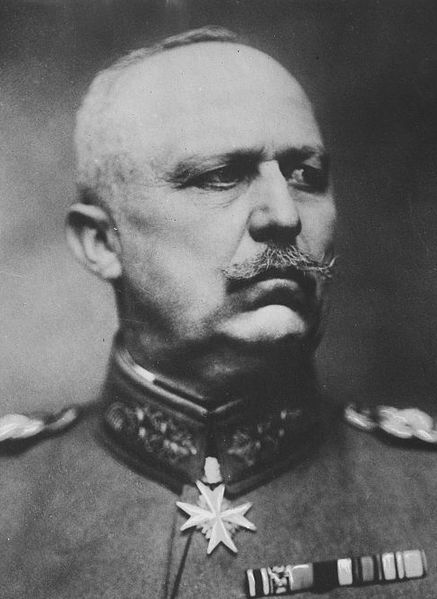

- General der Infanterie Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff, 1865

PAGE SPONSOR

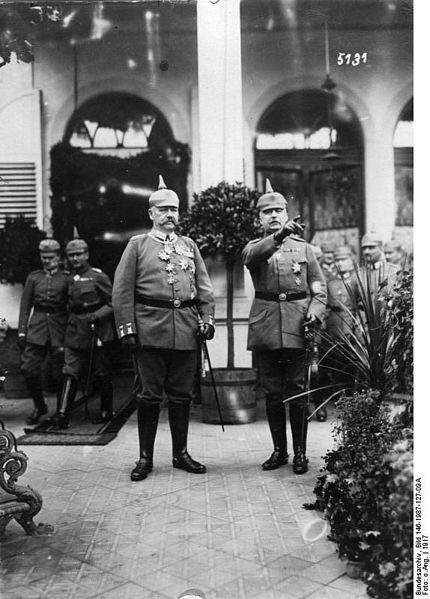

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (sometimes given incorrectly as von Ludendorff) (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German General, victor of Liège and of the Battle of Tannenberg (1914). From August 1916 his appointment as Generalquartiermeister made him joint head (with von Hindenburg) of Germany's effort in World War 1 until his resignation in October 1918.

After the war, Ludendorff became a prominent Right wing leader, and a promoter of the Dolchstoßlegende, convinced that the German Army had been betrayed by Leftists and Republicans in the Versailles Treaty. He took part in the unsuccessful coups d’état of Wolfgang Kapp in 1920 and the Beer Hall Putsch of Adolf Hitler in 1923, and in 1925 he ran for president against his former commander in chief, Paul von Hindenburg, whom he now bitterly hated. From 1924 to 1928 he represented the National Socialist Freedom Movement in the German Parliament. Consistently pursuing a purely military line of thought, Ludendorff developed, after the war, the theory of “Total War,”

which he published as Der Totale Krieg (The Nation at War) in 1935, in

which he argued that the entire physical and moral forces of the nation should be mobilized, because, according to him, peace was merely an interval between wars. Ludendorff was a reciepent of the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross and the Pour le Mérite. Ludendorff was born in Kruszewnia near Posen, Province of Posen (now Poznań County, Poland), the third of six children of August Wilhelm Ludendorff (1833 – 1905), descended from Pomeranian merchants, who had become a landowner in a modest sort of way, and who held a commission in the reserve cavalry.

Erich's mother, Klara Jeanette Henriette von Tempelhoff (1840 – 1914),

was the daughter of the noble but impoverished Friedrich August

Napoleon von Tempelhoff (1804 – 1868), and his wife Jeannette Wilhelmine

von Dziembowska (1816 – 1854) — she from a Germanised Polish landed

family on her father's side, and through whom Erich was a remote descendant of the Dukes of Silesia and the Marquesses and Electors of Brandenburg. He is said to

have had a stable and comfortable childhood, growing up on a small

family farm. He received his early schooling from his maternal aunt and

had a flair for mathematics. His acceptance into the Cadet School at Plön was

largely due to his proficiency in mathematics and the adherence to the

work ethic that he would carry with him throughout his life. Passing

his Entrance Exam with Distinction, he was put in a class two years ahead of his actual age group, and thereafter was consistently first in his class. Heinz Guderian attended the same Cadet School, which produced many well trained German officers. Despite Ludendorff's maternal noble origins, however, he married outside them, to Margarete née Schmidt (1875 – 1936). In 1885 he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 57th Infantry Regiment, at Wesel. Over the next eight years he saw further service as a first lieutenant with the 2nd Marine Battalion at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, and the 8th Grenadier Guards at Frankfurt (Oder). His service reports were of the highest order, with frequent commendations. In

1893 he was selected for the War Academy where the commandant, General

Meckel, recommended him for appointment to the General Staff. He was

appointed to the German General Staff in 1894, rising rapidly through the ranks to become a senior staff officer with V Corps HQ in 1902 – 04. In 1905, under von Schlieffen, he joined the Second Section of the Great General Staff in Berlin, responsible for the Mobilisation Section from 1904 – 13. By 1911 he was a full colonel. Ludendorff was involved in testing the minute details regarding the Schlieffen Plan, assessing the fortifications around the Belgian fortress city of Liège.

Most importantly, he attempted to prepare the German army for the war

he saw coming. The Social Democrats, who by the 1912 elections had

become the largest party in the Reichstag seldom gave priority to army expenditures, building up its reserves, or funding advanced weaponry such as Krupp's siege cannons. Funding for the military went to the Kaiserliche Marine.

He then tried to influence the Reichstag via the retired General Keim.

Finally the War Ministry caved in to political pressures about

Ludendorff's agitations and in January 1913 he was dismissed from the

General Staff and returned to regimental duties, commanding the 39th (Lower Rhine) Fusiliers at Düsseldorf. Ludendorff was convinced that his prospects in the military were nil but took up his mildly important position. Barbara Tuchman describes Ludendorff in her book The Guns of August as

Schlieffen’s devoted disciple who was a glutton for work and a man of

granite character. He was deliberately friendless and forbidding, and

remained little known or liked. Lacking a trail of reminiscences or

anecdotes as he grew in eminence, Ludendorff was a man without a shadow. However,

John Lee states that while Ludendorff was with his

Fusiliers "he became the perfect regimental commander... the younger

officers came to adore him". In April 1914 Ludendorff was promoted to Major - General and given the command of the 85th Infantry Brigade, stationed at Strassburg. With the outbreak of World War I, then called The Great War, Ludendorff was first appointed Deputy Chief of Staff to the German Second Army under General Karl von Bülow. His assignment was largely due to his knowledge and previous work investigating the dozen forts surrounding Liège, Belgium. The German assault in early August 1914, according to the Schlieffen Plan for invading France, gained him national recognition. The Germans experienced their first major setback at

Liège. Belgian artillery and machine guns killed thousands of

German troops attempting frontal assaults. On 5 August Ludendorff took

command of the 14th Brigade,

whose general had been killed. He cut off Liège and called for

siege guns. By 16 August all forts around Liège had fallen,

allowing the German First Army to advance. As the victor of

Liège, Ludendorff was awarded Germany's highest military

decoration for gallantry, the Pour le Mérite, presented by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself on 22 August. Russia

had prepared for and was waging war more effectively than the

Schlieffen Plan anticipated. German forces were withdrawing as the

Russians advanced towards Königsberg in East Prussia.

Only a week after Liège's fall, Ludendorff, then engaged in the

assault on Belgium's second great fortress at Namur, was urgently

requested by the Kaiser to serve as Chief of Staff of the Eighth Army on the Eastern Front. Ludendorff went quickly with Paul von Hindenburg, who was recalled from retirement, to replace General Maximilian von Prittwitz, who had proposed abandoning East Prussia altogether. Hindenburg relied heavily upon Ludendorff and Max Hoffmann in planning the successful operations in the battles of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes. After the Battle of Łódź (1914) in November 1914 Ludendorff was promoted to Lieutenant - General. In August 1916, Erich von Falkenhayn resigned

as Chief of the General Staff. Paul von Hindenburg took his place;

Ludendorff declined to be known as "Second Chief of the General Staff"

and instead insisted on the title First Generalquartiermeister, on condition that all orders were sent out jointly from the two men. Together they formed the so-called Third Supreme Command. As for his rank, he was promoted to General of the Infantry. Ludendorff was the chief manager of the German war effort, with the popular general von Hindenburg his pliant front man. Ludendorff advocated unrestricted submarine warfare to break the British blockade, which became an important factor in bringing the United States into

the war in April 1917. He proposed massive annexations and colonisation

in Eastern Europe in the event of the victory of the German Reich, and

was one of the main supporters of Polish Border Strip. Russia withdrew from the war in 1917 and Ludendorff participated in the meetings held between German and the new Bolshevik leadership. After much deliberation, the Treaty of Brest - Litovsk was signed in March 1918. That same spring Ludendorff planned and directed Germany's final Western Front offensives, including Operation Michael, Operation Georgette and Operation Bluecher;

although not formally a commander - in - chief, Ludendorff directed

operations by issuing orders to the staffs of the armies at the front,

as was perfectly normal under the German system of that time. This

final push to win the war fell short and as the German war effort

collapsed, Ludendorff's tenure of war - time leadership faded. On

8 August 1918, Ludendorff concluded the war had to be ended and ordered

his men to hold their positions while a ceasefire was negotiated.

Unfortunately, the German troops could not stop advances in the west by

the Allies, now reinforced by American troops. Ludendorff was near a

mental breakdown, sometimes in tears, and his worried staff called in a

psychiatrist. On 29 September the Kingdom of Prussia assumed

its pre-war authority, which lasted until Kaiser Wilhelm II's

abdication. Ludendorff had tried appealing directly to the American

government in the hope of getting better peace terms than from the

French and British. He then calculated that the civilian government

that he had created on 3 October would get better terms from the

Americans. However Ludendorff was frustrated by the terms that the new

government were negotiating during early October. Unable to achieve an

honourable peace himself, Ludendorff had handed over power to the new

civilian government, but he then blamed them for what he felt a

humiliating armistice that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was

proposing. He then decided in mid October that the army should hold out

until winter set in when defence would be easier, but the civilian

government continued to negotiate. Unable

to prevent negotiations, Ludendorff stated in his 1920 memoirs that he

had prepared a letter of resignation on the morning of 26 October, but

changed his mind after discussing the matter with von Hindenburg.

Shortly afterwards, he was informed that the Kaiser had dismissed him

at the urging of the Cabinet and was then called in for an audience

with the Kaiser where he tendered his resignation. On the day of the armistice, Ludendorff disguised himself in a false beard and glasses and went to the home of his brother, astronomer Hans Ludendorff, in Potsdam. A few days later, he boarded a steamer for Copenhagen. Though he was recognized, he continued from Denmark to Sweden.

In

exile, he wrote numerous books and articles about the German military's

conduct of the war while forming the foundation for the

Dolchstoßlegende, the Stab - in - the - back theory, for which he is considered largely responsible. Ludendorff

was convinced that Germany had fought a defensive war and, in his

opinion, Kaiser Wilhelm II had failed to organise a proper

counter propaganda campaign or provide efficient leadership. Ludendorff

was also extremely suspicious of the Social Democrats and leftists,

whom he blamed for the humiliation of Germany through the Versailles Treaty. Ludendorff also claimed that he paid close attention to the business element (especially the Jews),

and saw them turn their backs on the war effort by letting profit

dictate production and financing rather than patriotism. Again focusing

on the left, Ludendorff was appalled by the strikes that took place

towards the end of the war and saw the homefront collapse before the

front, with the former poisoning the morale of soldiers on temporary

leave. Most importantly, Ludendorff felt that the German people as a

whole had underestimated what was at stake in the war: he was convinced

that the Entente had started the war and was determined to dismantle

Germany completely. In what has been proven, Ludendorff wrote: Ludendorff returned to Germany in 1920. The Weimar Republic planned to send him and several other noted German generals (von Mackensen, among others) to reform the National Revolutionary Army of China,

but this was cancelled due to the limitations of the Treaty of

Versailles and the image problems with selling such a noted general out

as a mercenary. Throughout his life, Ludendorff maintained a strong

distaste for politicians and found most of them to be lacking an

energetic national spirit. However, Ludendorff's political philosophy

and outlook on the war brought him into right wing politics as a German nationalist and won his support that helped to pioneer the Nazi Party. Early on, Ludendorff also held Adolf Hitler in the highest regard. At Hitler's urging, Ludendorff took part in the Beer Hall Putsch in

1923. The plot failed and in the trial that followed Ludendorff was

acquitted. In 1924, he was elected to the Reichstag as a representative

of the NSFB (a coalition of the German Völkisch Freedom Party and members of the Nazi Party), serving until 1928. He ran in the 1925 presidential election against former commander Paul von Hindenburg and

received just 285,793 votes. Ludendorff's reputation may have been

damaged by the Putsch, but he conducted very little campaigning of his

own and remained aloof, relying almost entirely on his lasting image as

a war hero, an attribute which Hindenburg also possessed. After

1928, Ludendorff went into retirement, having fallen out with the Nazi

party. He no longer approved of Hitler and began to regard him as just

another manipulative politician, and perhaps worse. In his later years,

Ludendorff went into a relative seclusion with his second wife, Mathilde von Kemnitz (1874 – 1966), writing several books and leading the Tannenbergbund. He concluded that the world's problems were the result of Christians (especially of the Jesuits and Catholicism), Jews, and Freemasons. Together with Mathilde, he founded the "Bund für Gotteserkenntnis" (Society for the Knowledge of God), a small and rather obscure esoterical society of Theists that survives to this day. In an attempt to regain Ludendorff's favour, Hitler paid Ludendorff an unannounced visit in 1935 and offered to make him a Field Marshal. Infuriated, Ludendorff angrily replied, "a Field Marshal is born, not made". When Ludendorff died in Tutzing in

1937, he was given – against his explicit wishes, a state funeral

attended by Hitler, who declined to speak. He was buried in the Neuer

Friedhof in Tutzing.

“ By the Revolution the

Germans have made themselves pariahs among the nations, incapable of

winning allies, helots in the service of foreigners and foreign

capital, and deprived of all self-respect. In twenty years' time, the

German people will curse the parties who now boast of having made the

Revolution. ”