<Back to Index>

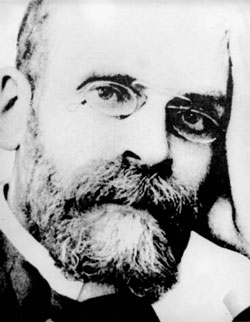

- Sociologist David Émile Durkheim, 1858

- Painter Pierre Étienne Théodore Rousseau, 1812

- Prime Minister of France René Pléven, 1901

PAGE SPONSOR

David Émile Durkheim (April 15, 1858 – November 15, 1917) was a French sociologist. One of his primary goals was to establish sociology as a recognized academic discipline, a goal in which he succeeded. He formally established it as an academic discipline and, with Karl Marx and Max Weber, is commonly cited as the principal architect of modern social science and father of sociology. He was also France's first professor of sociology.

Durkheim's first famous work was the The Division of Labor in Society (1893). He set up the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895, publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method. In 1896, he established the journal L'Année Sociologique. Durkheim's seminal monograph, Suicide (1897), a study of suicide rates amongst Catholic and Protestant populations, pioneered modern social research and served to distinguish social science from psychology or political philosophy. His classic work, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912), presented a theory of religion, comparing the socio - cultural lives of aboriginal and modern societies, further establishing his reputation.

Durkheim refined the positivism originally set forth by Auguste Comte, promoting epistemological realism and the hypothetico - deductive model. For him, sociology was the science of institutions, its aim being to discover structural "social facts". Durkheim was a major proponent of structural functionalism, a foundational perspective in both sociology and anthropology. In his view, social science should be purely holistic; that is, sociology should study phenomena attributed to society at large, rather than being limited to the specific actions of individuals. Throughout his career, Durkheim was concerned primarily with how societies could maintain their integrity and coherence in the modern era, when things such as shared religious and ethnic background could no longer be assumed; to that end he wrote much about the effect of laws, religion, education and similar forces on the society. Lastly, Durkheim was concerned with the practical implications of scientific knowledge.

Durkheim remained a dominant force in French intellectual life until his death in 1917, presenting numerous lectures and published works on a variety of topics, including the sociology of knowledge, morality, social stratification, religion, law, education, and deviance. Durkheimian terms such as "collective conscience" have since entered the popular discourse.

Durkheim was born in Épinal in Lorraine, coming from a long line of devout French Jews; his father, grandfather, and great - grandfather had been rabbis. He began his education in a rabbinical school, but at an early age, he decided not to follow in his family's rabbinical footsteps, and switched schools. Durkheim himself would lead a completely secular life. Much of his work was dedicated to demonstrating that religious phenomena stemmed from social rather than divine factors. While Durkheim chose not to follow in the family tradition, he did not sever ties with his family or with the Jewish community. Many of his most prominent collaborators and students were Jewish, and some were blood relations.

A precocious student, Durkheim entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in 1879, although he succeeded only in his third attempt. The entering class that year was one of the most brilliant of the nineteenth century and many of his classmates, such as Jean Jaurès and Henri Bergson would go on to become major figures in France's intellectual history. At the ENS, Durkheim studied under the direction of Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, a classicist with a social scientific outlook, and wrote his Latin dissertation on Montesquieu. At the same time, he read Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. Thus Durkheim became interested in a scientific approach to society very early on in his career. This meant the first of many conflicts with the French academic system, which had no social science curriculum at the time. Durkheim found humanistic studies uninteresting, turning his attention from psychology and philosophy to ethics and eventually, sociology. He finished second to last in his graduating class when he aggregated in philosophy in 1882.

There was no way that a man of Durkheim's views could receive a major academic appointment in Paris. From 1882 to 1887 he taught philosophy at several provincial schools. In 1885 he decided to leave for Germany, where for two years he studied sociology in Marburg, Berlin and Leipzig. As Durkheim indicated in several essays, it was in Leipzig that he learned to appreciate the value of empiricism and its language of concrete, complex things, in sharp contrast to the more abstract, clear and simple ideas of the Cartesian method. By 1886, as part of his doctoral dissertation, he had completed the draft of his The Division of Labor in Society, and was working towards establishing the new science of sociology.

Durkheim's period in Germany resulted in the publication of numerous articles on German social science and philosophy; Durkheim was particularly impressed by the work of Wilhelm Wundt. Durkheim's articles gained recognition in France, and he received a teaching appointment in the University of Bordeaux in 1887, where he was to teach the university's first social science course. His official title was Chargé d'un Course de Science Social et de Pedagogie and thus he taught both pedagogy and sociology (the latter had never been taught in France before). The appointment of the social scientist to the mostly humanistic faculty was an important sign of the change of times, and the growing importance and recognition of the social sciences. From this position Durkheim helped reform the French school system and introduced the study of social science in its curriculum. However, his controversial beliefs that religion and morality could be explained in terms purely of social interaction earned him many critics.

Also in 1887, Durkheim married Louise Dreyfus. They would have two children, Marie and André.

The 1890s were a period of remarkable creative output for Durkheim. In 1892, he published The Division of Labour in Society, his doctoral dissertation and fundamental statement of the nature of human society and its development. Durkheim's interest in social phenomena was spurred on by politics. France's defeat in the Franco - Prussian War led to the fall of the regime of Napoleon III, which was then replaced by the Third Republic. This in turn resulted in a backlash against the new secular and republican rule, as many people considered a vigorously nationalistic approach necessary to rejuvenate France's fading power. Durkheim, a Jew and a staunch supporter of the Third Republic with a sympathy towards socialism, was thus in the political minority, a situation which galvanized him politically. The Dreyfus affair of 1894 only strengthened his activist stance.

In 1895, he published Rules of the Sociological Method, a manifesto stating what sociology is and how it ought to be done, and founded the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux. In 1898, he founded the L'Année Sociologique, the first French social science journal. Its aim was to publish and publicize the work of what was, by then, a growing number of students and collaborators (this is also the name used to refer to the group of students who developed his sociological program). Durkheim was familiar with several foreign languages and reviewed academic papers in German, English, and Italian for the journal. In 1897, he published Suicide, a case study which provided an example of what the sociological monograph might look like. Durkheim was one of the pioneers of using quantitative methods in criminology during his suicide case study.

By 1902, Durkheim had finally achieved his goal of attaining a prominent position in Paris when he became the chair of education at the Sorbonne.

Durkheim aimed for the Parisian position earlier, but the Parisian

faculty took longer to accept what some called "sociological imperialism" and admit social science to their curriculum. He

became a full professor (Professor of the Science of Education) there

in 1906, and in 1913 he was named Chair in "Education and Sociology". Because French universities are

technically institutions for training secondary school teachers, this

position gave Durkheim considerable influence — his lectures were the

only ones that were mandatory for the entire student body. Durkheim had

much influence over the new generation of teachers; around that time he

also served as an advisor to the Ministry of Education. In 1912, he published his last major work, The Elementary Forms of The Religious Life. The outbreak of World War I was to have a tragic effect on Durkheim's life. His leftism was

always patriotic rather than internationalist — he sought a secular,

rational form of French life. But the coming of the war and the

inevitable nationalist propaganda that

followed made it difficult to sustain this already nuanced position.

While Durkheim actively worked to support his country in the war, his

reluctance to give in to simplistic nationalist fervor (combined with

his Jewish background) made him a natural target of the now ascendant French Right.

Even more seriously, the generation of students that Durkheim had

trained were now being drafted to serve in the army, and many of them

perished in the trenches. Finally, Durkheim's own son, André,

died on the war front in December 1915 — a loss from which Durkheim never

recovered. Emotionally devastated, Durkheim collapsed of a stroke in Paris in 1917. He was buried at the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. Marcel Mauss, a notable social anthropologist of the pre-war era, was his nephew.