<Back to Index>

- Neurologist Jules Bernard Luys, 1828

- Composer Petrus Leonardus Leopoldus "Peter" Benoit, 1834

- Emperor of Austria Charles I, 1887

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles I (Karl Franz Joseph Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Marie von Habsburg - Lothringen) (17 August 1887 – 1 April 1922) was (among other titles) the last ruler of the Austro - Hungarian Empire. He was the last Emperor of Austria, the last King of Hungary, the last King of Bohemia, Croatia and the last King of Galicia and Lodomeria and the last monarch of the House of Habsburg - Lorraine. He reigned as Charles I as Emperor of Austria and Charles IV as King of Hungary from 1916 until 1918, when he "renounced participation" in state affairs, but did not abdicate. He spent the remaining years of his life attempting to restore the monarchy until his death in 1922. Following his beatification by the Catholic Church, he has become commonly known as the Blessed Charles of Austria.

Karl was born on 17 August 1887, in the Castle of Persenbeug in Lower Austria. He was the son of Archduke Otto Franz of Austria (1865 – 1906) and Princess Maria Josepha of Saxony (1867 – 1944); he was also a nephew of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria - Este. As a child, Charles was reared a devout Catholic. In 1911, Charles married Princess Zita of Parma.

Charles became heir - presumptive with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, his uncle, in Sarajevo in 1914, the event which precipitated World War I. Karl's reign began in 1916, when his grand - uncle, Franz Josef I of Austria died. Karl also became a Generalfeldmarschall in the Austro - Hungarian Army. On 2 December 1916, he took over the title of Supreme Commander of the whole army from Archduke Frederick.

His coronation occurred on 30 December. In 1917, Charles secretly

entered into peace negotiations with France. Although his foreign

minister, Ottokar Czernin,

was only interested in negotiating a general peace which would include

Germany as well, Charles himself, in negotiations with the French with

his brother - in - law, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon - Parma,

an officer in the Belgian Army, as intermediary, went much further in

suggesting his willingness to make a separate peace. When news of the

overture leaked in April 1918, Charles denied involvement until the

French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau published

letters signed by him. This led to Czernin's resignation, forcing

Austria - Hungary into an even more dependent position with respect to

its seemingly wronged German ally. The

Austro - Hungarian Empire was wracked by inner turmoil in the final years

of the war, with much tension between ethnic groups. As part of his Fourteen Points, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson demanded

that the Empire allow for autonomy and self - determination of its

peoples. In response, Charles agreed to reconvene the Imperial

Parliament and allow for the creation of a confederation with

each national group exercising self - governance. However, the ethnic

groups fought for full autonomy as separate nations, as they were now

determined to become independent from Vienna at the earliest possible

moment. Foreign Minister Baron Istvan Burián asked

for an armistice based on the Fourteen Points on 14 October, and two

days later Charles issued a proclamation that radically changed the

nature of the Austrian state. The Poles were granted full independence

with the purpose of joining their ethnic brethren in Russia and Germany

in a Polish state. The rest of the Austrian lands were transformed into

a federal union composed of four parts — German, Czech, South Slav and

Ukrainian. Each of the four parts was to be governed by a federal council, and Trieste was to receive a special status. However, Secretary of State Robert Lansing replied

four days later that the Allies were now committed to the causes of the

Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs. Therefore, autonomy for the

nationalities was no longer enough. In fact, a Czechoslovak provisional government had joined the Allies on 14 October, and the South Slav national council declared an independent South Slav state on October 29, 1918. The

Lansing note effectively ended any efforts to keep the Empire together.

One by one, the nationalities proclaimed their independence; even

before the note the national councils had been acting more like

provisional governments. Charles' political future became uncertain. On

31 October, Hungary officially ended the personal union between

Austria and Hungary. Nothing remained of Charles' realm except the

Danubian and Alpine provinces, and he was challenged even there by the German Austrian State Council. His last prime minister, Heinrich Lammasch, advised him that it was fruitless to stay on. On

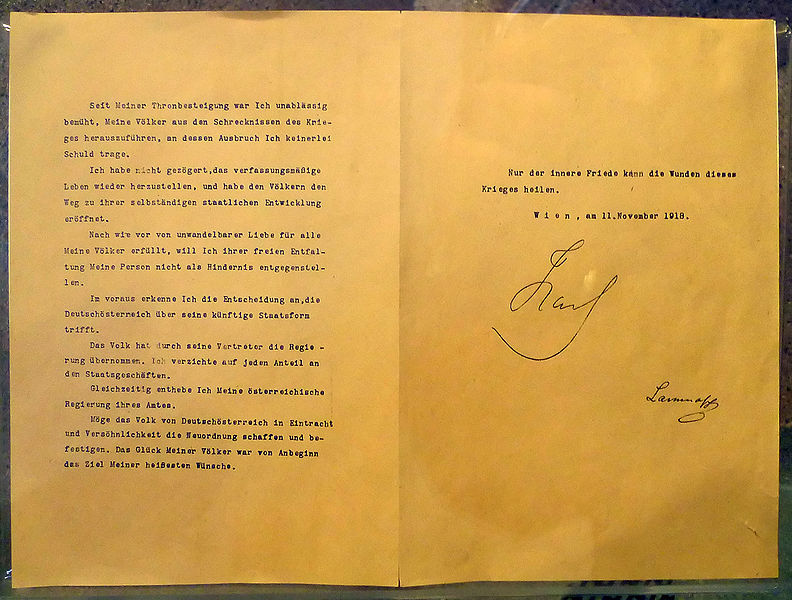

11 November 1918 — the same day as the armistice ending the war between

allies and Germany — Charles issued a carefully worded proclamation in

which he recognized the Austrian people's right to determine the form

of the state and "relinquish(ed) every participation in the

administration of the State." He

also released his officials from their oath of loyalty to him. On the

same day the Imperial Family left Schönbrunn and moved to Castle Eckartsau,

east of Vienna. On 13 November, following a visit of Hungarian

magnates, Charles issued a similar proclamation for Hungary. Although

it has widely been cited as an "abdication", that word was never

mentioned in either proclamation. Indeed, he deliberately avoided using the word abdication in

the hope that the people of either Austria or Hungary would vote to

recall him. Privately, Charles left no doubt that he believed himself

to be the rightful emperor. Addressing Cardinal Friedrich Gustav Piffl, he wrote: Instead, on 12 November, the day after he issued his proclamation, the independent Republic of German Austria was proclaimed, followed by the proclamation of the Hungarian Democratic Republic on 16 November. An uneasy truce - like situation ensued and persisted until 23 March 1919, when Charles left for Switzerland, escorted by the commander of the small British guard detachment at Eckartsau, Lt. Col. Edward Lisle Strutt.

As the Imperial Train left Austria on 24 March, Charles issued another

proclamation in which he confirmed his claim of sovereignty, declaring

that "whatever the national assembly of German Austria has resolved

with respect to these matters since 11 November is null and void for me

and my House." Although

the newly-established republican government of Austria was not aware of

this "Manifesto of Feldkirchen" at this time (it had been dispatched

only to the Spanish King and to the Pope through diplomatic channels),

the politicians now in power were extremely irritated by the Emperor's

departure without an explicit abdication. On 3 April 1919, the Austrian

Parliament passed the Habsburg Law,

which permanently barred Charles and Zita from ever returning to

Austria again. Other Habsburgs were banished from Austrian territory

unless they renounced all intentions of reclaiming the throne and

accepted the status of ordinary citizens. Another law, passed on the

same day, abolished all nobility in Austria. In Switzerland, Charles and his family briefly took residence at Castle Wartegg near Rorschach at Lake Constance, and moved to Château de Prangins at Lake Geneva on 20 May 1919.

Encouraged

by Hungarian royalists ("legitimists"), Charles sought twice in 1921 to

reclaim the throne of Hungary, but failed largely because Hungary's regent, Miklós Horthy (the

last admiral of the Austro - Hungarian Navy), refused to support him.

Horthy's failure to support Charles' restoration attempts is often

described as "treasonous" by royalists. Critics suggest that Horthy's

actions were more firmly grounded in political reality than those of

Charles and his supporters. Indeed, the neighbouring countries had

threatened to invade Hungary if Charles tried to regain the throne.

Later in 1921, the Hungarian parliament formally nullified the Pragmatic Sanction -- an act that effectively dethroned the Habsburgs. After the second failed attempt at restoration in Hungary, Charles and the pregnant Zita were briefly quarantined at Tihany Abbey. On 1 November 1921 they were taken to the Danube harbor city of Baja, made to board the British monitor HMS Glowworm, and were removed to the Black Sea where they were transferred to the light cruiser HMS Cardiff. They arrived in their final exile, the Portuguese island of Madeira,

on 19 November 1921. Determined to prevent a third restoration attempt,

the Council of Allied Powers had agreed on Madeira because it was

isolated in the Atlantic and easily guarded. Originally the couple and their children (who joined them only on 2 February 1922) lived at Funchal at the Villa Vittoria, next to Reid's Hotel, and later moved to Quinta do Monte. Compared to the imperial glory in Vienna and even at Eckartsau, conditions there were certainly impoverished, although

not nearly comparable to the bleak conditions under which most of

Charles' former subjects had to make a living after the war. During his

stay on the island, his personal chaplain was the priest, Father Jorge de Faria e Castro. Charles

would not leave Madeira again. On 9 March 1922 he caught a cold walking

into town and developed bronchitis which subsequently progressed to

severe pneumonia. Having suffered two heart attacks he died of respiratory failure on 1 April in the presence of his wife (who was pregnant with their eighth child) and 9 year old Crown Prince Otto, retaining consciousness almost to the last moment. His

remains except for his heart are still kept on the island, in the

Church of Our Lady of Monte, in spite of several attempts to move them

to the Habsburg Crypt in Vienna. His heart, and that of Empress Zita, repose in the Loreto Chapel of Muri Abbey. Historians have been mixed in their evaluations of Charles and his reign. One of the most critical has been Helmut Rumpler, head of the Habsburg commission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences,

who has described Charles as "a dilettante, far too weak for the

challenges facing him, out of his depth, and not really a politician."

However, others have seen Charles as a brave and honourable figure who

tried as Emperor - King to halt World War I. The English writer, Herbert Vivian, wrote: "Karl

was a great leader, a Prince of peace, who wanted to save the world

from a year of war; a statesman with ideas to save his people from the

complicated problems of his Empire; a King who loved his people, a

fearless man, a noble soul, distinguished, a saint from whose grave

blessings come." Furthermore, Anatole France, the French novelist, stated: "Emperor

Karl is the only decent man to come out of the war in a leadership

position, yet he was a saint and no one listened to him. He sincerely

wanted peace, and therefore was despised by the whole world. It was a

wonderful chance that was lost." Paul von Hindenburg, who at the time of Charles' reign was German army commander in chief, commented in his memoirs: "He

tried to compensate for the evaporation of the ethical power which

emperor Franz Joseph had represented by offering ethnical

reconciliation. Even as he dealt with elements who were sworn to the

goal of destroying his empire he believed that his acts of political

grace would have an impact on their conscience. These attempts were

totally futile; those people had long ago lined up with our common

enemies, and were far from being deterred." Catholic Church leaders

have praised Charles for putting his Christian faith first in making

political decisions, and for his role as a peacemaker during the war,

especially after 1917. They have considered that his brief rule

expressed Roman Catholic social teaching, and that he created a social legal framework that in part still survives. Pope John Paul II declared Charles "Blessed" in a beatification ceremony held on 3 October 2004, and stated: From

the beginning, the Emperor Charles conceived of his office as a holy

service to his people. His chief concern was to follow the Christian

vocation to holiness also in his political actions. For this reason,

his thoughts turned to social assistance.