<Back to Index>

- Archaeologist James Henry Breasted, 1865

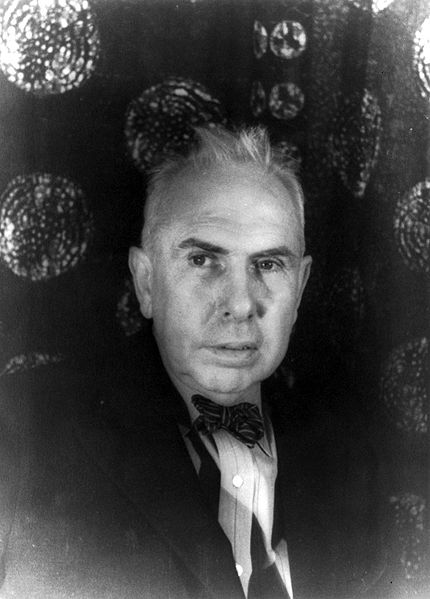

- Writer Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser, 1871

- Duke of Saxony George the Bearded, 1471

PAGE SPONSOR

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist. He pioneered the naturalist school and is known for portraying characters whose value lies not in their moral code, but in their persistence against all obstacles, and literary situations that more closely resemble studies of nature than tales of choice and agency.

Dreiser was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, to Sarah and John Paul Dreiser, a strict Catholic family. John Paul Dreiser was a German immigrant from Mayen in the Eifel region, and Sarah was from the Mennonite farming community near Dayton, Ohio; she was disowned for marrying John and converting to Roman Catholicism. Theodore was the twelfth of thirteen children (the ninth of the ten surviving). The popular songwriter Paul Dresser (1857 – 1906) was his older brother.

From 1889 to 1890, Theodore attended Indiana University before dropping out. Within several years, he was writing for the Chicago Globe newspaper and then the St. Louis Globe - Democrat. He wrote several articles on writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, William Dean Howells, Israel Zangwill, John Burroughs, and interviewed public figures such as Andrew Carnegie, Marshall Field, Thomas Edison, and Theodore Thomas. Other interviewees included Lillian Nordica, Emilia E. Barr, Philip Armour and Alfred Stieglitz. After proposing in 1893, he married Sara White on December 28, 1898. They ultimately separated in 1909, partly as a result of Dreiser's infatuation with Thelma Cudlipp, the teenage daughter of a work colleague, but were never formally divorced.

In 1919 Dreiser met his cousin Helen Richardson with whom he began an affair with sado - masochistic elements. They eventually married on 13 June 1944.

His first novel,

Sister Carrie (1900), tells the story of a woman who flees her country life for the city (Chicago)

and there lives a life far from a Victorian ideal. It sold poorly and

was not widely promoted largely because of moral objections to the

depiction of a country girl who pursues her dreams of fame and fortune

through relationships to men. The book has since acquired a

considerable reputation. It has been called the "greatest of all

American urban novels." (It was made into a 1952 film by William Wyler, which starred Laurence Olivier and Jennifer Jones.)

He witnessed a lynching in 1893 and wrote the short story, Nigger Jeff, which appeared in Ainslee's Magazine in 1901.

His second novel, Jennie Gerhardt, was published in 1911. Many of Dreiser's subsequent novels dealt with social inequality. His first commercial success was An American Tragedy (1925), which was made into a film in 1931 and again in 1951 (as A Place in the Sun). Already in 1892, when Dreiser began work as a newspaperman he had begun "to observe a certain type of crime in the United States that proved very common. It seemed to spring from the fact that almost every young person was possessed of an ingrown ambition to be somebody financially and socially." "Fortune hunting became a disease" with the frequent result of a peculiarly American kind of crime, a form of "murder for money", when "the young ambitious lover of some poorer girl" found "a more attractive girl with money or position" but could not get rid of the first girl, usually because of pregnancy. Dreiser claimed to have collected such stories every year between 1895 and 1935. The murder in 1911 of Avis Linnell by Clarence Richeson particularly caught his attention. By 1919 this murder was the basis of one of two separate novels begun by Dreiser. The 1906 murder of Grace Brown by Chester Gillette eventually became the basis for An American Tragedy.

Though primarily known as a novelist, Dreiser published his first collection of short stories, Free and Other Stories in 1918. The collection contained 11 stories. Another story, "My Brother Paul", was a brief biography of his older brother, Paul Dresser, who was a famous songwriter in the 1890s. This story was the basis for the 1942 romantic movie, "My Gal Sal".

Other works include The "Genius" and Trilogy of Desire (a three - parter based on the remarkable life of the Chicago streetcar tycoon Charles Tyson Yerkes and composed of The Financier (1912), The Titan (1914), and The Stoic. The latter was published posthumously in 1947.

Dreiser

was often forced to battle against censorship because of his depiction

of some aspects of life, such as sexual promiscuity, offended authorities and popular opinion. Politically, Dreiser was involved in several campaigns against social injustice. This included the lynching of Frank Little, one of the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World, the Sacco and Vanzetti case, the deportation of Emma Goldman, and the conviction of the trade union leader Tom Mooney. In November 1931, Dreiser led the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners (NCDPP) to the coalfields of southeastern Kentucky, where they took testimony from coal miners in Pineville and Harlan on the violence against the miners and their unions by the coal operators. Dreiser was a committed socialist, and wrote several non-fiction books on political issues. These included Dreiser Looks at Russia (1928), the result of his 1927 trip to the Soviet Union, and two books presenting a critical perspective on capitalist America, Tragic America (1931) and America Is Worth Saving (1941).

His vision of capitalism and a future world order with a strong

American military dictate combined with the harsh criticism of the

latter made him unpopular within the official circles. Although less

politically radical friends, such as H.L. Mencken,

spoke of Dreiser's relationship with communism as an "unimportant

detail in his life," Dreiser's biographer Jerome Loving notes that his

political activities since the early 1930s had "clearly been in concert

with ostensible communist aims with regard to the working class.". Dreiser died on December 28, 1945 in Hollywood at the age of 74. Dreiser had an enormous influence on the generation that followed his. In his tribute "Dreiser" from Horses and Men (1923), Sherwood Anderson writes: Alfred Kazin characterized

Dreiser as "stronger than all the others of his time, and at the same

time more poignant; greater than the world he has described, but as

significant as the people in it," while Larzer Ziff (UC

Berkeley) remarked that Dreiser "succeeded beyond any of his

predecessors or successors in producing a great American business

novel." Arguably, Dreiser succeeded beyond any of his predecessors or

successors in producing the great American novel. Renowned mid-century literary critic Irving Howe spoke of Dreiser as "among the American giants, one of the very few American giants we have had." A British view of Dreiser came from the publisher Rupert Hart - Davis:

"Theodore Dreiser's books are enough to stop me in my tracks, never

mind his letters — that slovenly turgid style describing endless

business deals, with a seduction every hundred pages as light relief.

If he's the great American novelist, give me the Marx Brothers every time." One

of Dreiser's strongest champions during his lifetime, H.L. Mencken,

declared "that he is a great artist, and that no other American of his

generation left so wide and handsome a mark upon the national letters.

American writing, before and after his time, differed almost as much as

biology before and after Darwin. He was a man of large originality, of

profound feeling, and of unshakable courage. All of us who write are

better off because he lived, worked, and hoped." Dreiser's great theme was the tremendous tensions that can arise among ambition, desire, and social mores. In 2008, the Library of America selected

Dreiser’s article “Dreiser Sees Error in Edwards Defense” for inclusion

in its two - century retrospective of American True Crime.