<Back to Index>

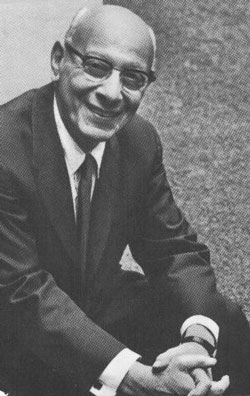

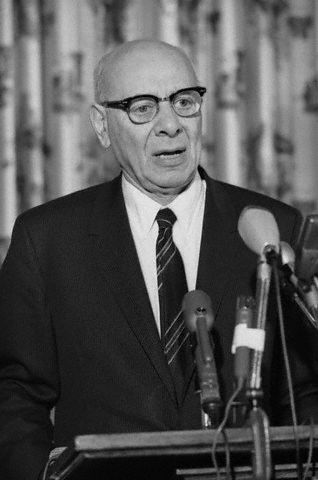

- Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, 1903

- Painter Rudolf Ritter von Alt, 1812

- Surgeon General of the U.S. Army William Alexander Hammond, 1828

PAGE SPONSOR

Bruno Bettelheim (August 28, 1903 – March 13, 1990) was an Austrian born American child psychologist and writer. He gained an international reputation for his work on Freud, psychoanalysis, and emotionally disturbed children.

When his father died, Bettelheim left his studies at the University of Vienna to look after his family's sawmill. Bettelheim and his first wife Gina took care of Patsy, an American child whom he later described as autistic. Patsy lived in the Bettelheim home in Vienna for seven years. Having discharged his obligations to his family's business, Bettelheim returned as a mature student in his 30s to the University of Vienna. He earned a degree in philosophy, producing a dissertation on Immanuel Kant and on the history of art. In the Austrian academic culture of Bettelheim's time, one could not study the history of art without mastering aspects of psychology. Candidates for the doctoral dissertation in the History of Art in 1938 at Vienna University had to fulfill prerequisites in the formal study of the role of Jungian archetypes in art, and in art as an expression of the Freudian subconscious.

Though Jewish by birth, Bettelheim grew up in a secular family. After the merging of Austria into Greater Germany (April 1938), the authorities sent him with other Austrian Jews to Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps for

11 months from 1938 to 1939. In Buchenwald he met and befriended the

social psychologist Ernst Federn. As a result of an amnesty declared for Hitler's

birthday (April 20, 1939), Bettelheim and hundreds of other prisoners

regained their freedom. Bettelheim drew on the experience of the

concentration camps for some of his later work.

Bettelheim arrived by ship as a refugee in New York City in the fall of 1939 to join his wife Gina, who had already emigrated. They divorced because she had become involved with someone else during their separation. He soon moved to Chicago and became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1944 and remarried to an American.

The University of Chicago appointed Bettelheim as a professor of psychology and he taught there from 1944 until his retirement in 1973. He had trained in philosophy, but stated also that the Viennese psychoanalyst Richard Sterba had analyzed him.

Bettelheim also served as Director of the University of Chicago's Sonia Shankman Orthogenic School, a home that treats emotionally disturbed children. He made changes and set up an environment for milieu therapy, in which children could form strong attachments with adults within a structured but caring environment. He claimed considerable success in treating some of the emotionally disturbed children. He wrote books on both normal and abnormal child psychology and became a major influence in the field, widely respected during his lifetime. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1971.

Among numerous other works, Bruno Bettelheim wrote The Uses of Enchantment, published in 1976. In this book he analyzed fairy tales in terms of Freudian psychology. The book won the U.S. Critic's Choice Prize for criticism in 1976 and the National Book Award in the category of Contemporary Thought in 1977. Bettelheim discussed the emotional and symbolic importance of fairy tales for children, including traditional tales at one time considered too dark, such as those collected and published by the Brothers Grimm. Bettelheim suggested that traditional fairy tales, with the darkness of abandonment, death, witches, and injuries, allowed children to grapple with their fears in remote, symbolic terms. If they could read and interpret these fairy tales in their own way, he believed, they would get a greater sense of meaning and purpose. Bettelheim thought that by engaging with these socially evolved stories, children would go through emotional growth that would better prepare them for their own futures.

His writings covered a wide range of topics, beginning shortly after he arrived in the United States with an essay on concentration camps and their dynamics. He long had a reputation as an authority on these topics.

At the end of his life Bettelheim suffered from depression. He appeared to have had difficulties with depression for much of his life. In 1990, widowed, in failing physical health, and suffering from the effects of a stroke which impaired his mental abilities and paralyzed part of his body, he committed suicide as a result of self - induced asphyxiation by placing a plastic bag over his head.

Bettelheim became one of the most prominent defenders of

Hannah Arendt's book Eichmann in Jerusalem. He wrote a positive review forThe New Republic. This

review prompted a letter from the writer Harry Golden, who alleged that

both Bettelheim and Arendt suffered from "an essentially Jewish

phenomenon… self-hatred".

Bettelheim subscribed to and became a prominent proponent of the "refrigerator mother" theory of autism: the theory that autistic behaviors stem from the emotional frigidity of the children's mothers, a view that enjoyed considerable influence into the 1960s and 1970s in the United States. However, some indications suggest that he later changed his thinking. Bettelheim's 1967 book The Empty Fortress: Infantile Autism and the Birth of the Self, which promoted the "refrigerator mother" theory of autism, enjoyed wide success, especially in the popular press. The book played a key role in ensuring that the "refrigerator mother" theory soon became the accepted explanation for autism in popular culture and, to a considerable extent, in professional circles.

Subsequently, medical research has provided greater understanding of biological bases of autism and other illnesses. Scientists, most notably Bernard Rimland, have largely discredited Bettelheim's views on autism, although as of 2009 the "refrigerator mother" theory still retains some prominent supporters.

In addition to reassessment of Bettelheim's psychological theories, controversy has arisen related to his history and personality. He had a prominent reputation as a compassionate man who had made a career of healing others and as an expert on the dynamics of the concentration camps.

After Bettelheim's suicide in 1990, detractors claimed that Bettelheim had a dark side. They alleged that he exploded in screaming anger at students, and went beyond firm treatment to corporal punishment or child abuse. Three former patients questioned his work and characterized him as a cruel tyrant. Roberta Carly Redford, a student at the Orthogenic School from age 16 to 23, claims in her book Crazy: My Seven Years at Bruno Bettelheim's Orthogeneic School that she was "beaten regularly, emotionally abused, and subjected to a variety of humiliations. Bettelheim himself was a key part of this treatment." Other former patients wrote or spoke publicly to tell how much Bettelheim had helped them, so there seemed to be no consensus.

Two biographies published in the 1990s revealed evidence that Bettelheim had lied about or exaggerated many parts of his background. These included wartime experiences, family life, academic credentials and the use of corporal punishment at the Orthogenic School. While Richard Pollak's biography expressed a strongly negative view of Bettelheim, that by Nina Sutton offered a different interpretation of some of the material. Gaps emerged between the public reputation Bettelheim had established in the US and some of the facts revealed during this controversy, but some commentators made charges that related to Bettelheim's personality.

The resulting discussions and controversy called into question whether the University of Chicago had screened Bettelheim closely enough, although appointments to administrative positions such as director of the school do not require an academic appointment. Many parents who had children at the school claimed that his treatment had helped their children and continued to consider him a compassionate man.

According

to Bettelheim, children — when treated with loving care — will

internalize the care and love experienced in childhood respecting their

bodies and their own person. The

loving attitude of the parents towards the body of their child and its

actions will transform into the child's holding its own body in high

esteem, wishing to care for and protect it.

In 1974 a four - part series featuring Bruno Bettelheim and directed by Daniel Carlin appeared on French television — Portrait de Bruno Bettelheim. Woody Allen included Bettelheim as himself in a cameo in the film Zelig (1983). A BBC Horizon documentary about Bettelheim was screened in 1986.

Two former patients wrote about their experiences at the Orthogenics School, one in a novel and one in a memoir. Tom Lyons' novel The Pelican and After appeared in 1983. Stephen Eliot's brought out his memoir, Not the Thing I Was: Thirteen Years at Bruno Bettelheim's Orthogenics School, in 2003.