<Back to Index>

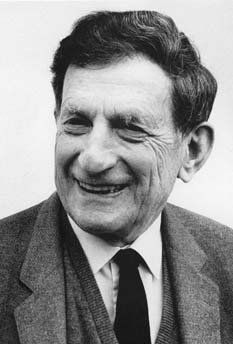

- Physicist David Joseph Bohm, 1917

- Painter Ivana Kobilca, 1861

- President of South Korea Kim Young-sam, 1927

PAGE SPONSOR

David Joseph Bohm (20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American born British quantum physicist who contributed to theoretical physics, philosophy, neuropsychology, and the Manhattan Project.

Bohm was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania to a Hungarian Jewish immigrant father and a Lithuanian Jewish mother. He was raised mainly by his father, a furniture store owner and assistant of the local rabbi. Bohm attended Pennsylvania State College (now The Pennsylvania State University), graduating in 1939, then attended the California Institute of Technology for a year, and then transferred to the theoretical physics group directed by Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley, where he eventually obtained his doctorate degree.

Bohm lived in the same neighborhood as some of Oppenheimer's other graduate students (Giovanni Rossi Lomanitz, Joseph Weinberg, and Max Friedman) and with them became increasingly involved not only with physics, but with radical politics. Bohm became active in organizations like the Young Communist League, the Campus Committee to Fight Conscription, and the Committee for Peace Mobilization all later termed Communist organizations by J. Edgar Hoover's FBI. During World War II, the Manhattan Project mobilized much of Berkeley's physics research in the effort to produce the first atomic bomb. Though Oppenheimer had asked Bohm to work with him at Los Alamos (the top secret laboratory established in 1942 to design the atom bomb), the director of the Manhattan Project, General Leslie Groves,

would not approve Bohm's security clearance, after evidence about his

politics (Bohm's friend, Joseph Weinberg, had also been suspected for espionage). Bohm

remained in Berkeley, teaching physics, until he completed his Ph.D. in

1943, by an unusually ironic circumstance. According to Peat, "the scattering calculations (of

collisions of protons and deuterons) that he had completed proved

useful to the Manhattan Project and were immediately classified.

Without security clearance, Bohm was denied access to his own work; not

only would he be barred from defending his thesis, he was not even

allowed to write his own thesis in the first place!" To satisfy the

university, Oppenheimer certified that Bohm had successfully completed

the research. He later performed theoretical calculations for the Calutrons at the Y-12 facility in Oak Ridge, used to electromagnetically enrich uranium for use in the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. After the war, Bohm became an assistant professor at Princeton University, where he worked closely with Albert Einstein. In May, 1949, at the beginning of the McCarthyism period, the House Un-American Activities Committee called upon Bohm to testify before it — because of his previous ties to suspected Communists. Bohm, however, pleaded the Fifth amendment right to refuse to testify, and refused to give evidence against his colleagues. In

1950, Bohm was charged for refusing to answer questions of the

Committee and was arrested. He was acquitted in May, 1951, but

Princeton University had already suspended him. After the acquittal,

Bohm's colleagues sought to have him re-instated to Princeton, and

Einstein reportedly wanted Bohm to serve as his assistant. The university, however, did not renew his contract. Bohm then left for Brazil to assume a professorship of Physics at the University of São Paulo.

During his early period, Bohm made a number of significant contributions to physics, particularly to quantum mechanics and relativity theory. As a post - graduate at Berkeley, he developed a theory of plasmas, discovering the electron phenomenon known now as Bohm diffusion. His first book, Quantum Theory published

in 1951, was well received by Einstein, among others. However, Bohm

became dissatisfied with the orthodox interpretation of quantum theory,

which he had written about in that book, and began to develop his own

interpretation (De Broglie – Bohm theory) — a non-local hidden variable deterministic theory the predictions of which agree perfectly with the nondeterministic quantum theory. His work and the EPR argument became the major factor motivating John Bell's inequality, the consequences of which are still being investigated.

In 1955, Bohm relocated to Israel, where he spent two years working at the Technion at Haifa. Here he met Sarah Woolfson (also called Saral). The couple married in 1956. In 1957, Bohm relocated to the United Kingdom as a research fellow at the University of Bristol. In 1959, Bohm and his student Yakir Aharonov discovered the Aharonov - Bohm effect,

showing how a magnetic field could affect a region of space in which

the field had been shielded, although its vector potential did not

vanish there. This showed for the first time that the magnetic vector potential,

hitherto a mathematical convenience, could have real physical (quantum)

effects. In 1961, Bohm was made Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of London's Birkbeck College, where his collected papers are kept.

In collaboration with Stanford neuroscientist Karl Pribram Bohm was involved in the early development of the holonomic model of the functioning of the brain, a model for human cognition that is drastically different from conventionally accepted ideas. Bohm worked with Pribram on the theory that the brain operates in a manner similar to a hologram, in accordance with quantum mathematical principles and the characteristics of wave patterns.

Bohm

was alarmed by what he considered an increasing imbalance of not only

man and nature, but among peoples, as well as people, themselves. Bohm:

"So one begins to wonder what is going to happen to the human race.

Technology keeps on advancing with greater and greater power, either

for good or for destruction." He goes on to ask: What

is the source of all this trouble? I'm saying that the source is

basically in thought. Many people would think that such a statement is

crazy, because thought is the one thing we have with which to solve our

problems. That's part of our tradition. Yet it looks as if the thing we

use to solve our problems with is the source of our problems. It's like

going to the doctor and having him make you ill. In fact, in 20% of

medical cases we do apparently have that going on. But in the case of

thought, it's far over 20%. In Bohm's view: ...the

general tacit assumption in thought is that it's just telling you the

way things are and that it's not doing anything - that 'you' are inside

there, deciding what to do with the info. But you don't decide what to

do with the info. Thought runs you. Thought, however, gives false info

that you are running it, that you are the one who controls thought.

Whereas actually thought is the one which controls each one of us.

Thought is creating divisions out of itself and then saying that they

are there naturally. This is another major feature of thought: Thought

doesn't know it is doing something and then it struggles against what

it is doing. It doesn't want to know that it is doing it. And thought

struggles against the results, trying to avoid those unpleasant results

while keeping on with that way of thinking. That is what I call

"sustained incoherence". Bohm thus proposes in his book, Thought as a System, a pervasive, systematic nature of thought: What I mean by "thought" is the whole thing - thought, felt, the

body, the whole society sharing thoughts - it's all one process. It is

essential for me not to break that up, because it's all one process;

somebody else's thoughts becomes my thoughts, and vice versa. Therefore

it would be wrong and misleading to break it up into my thoughts, your

thoughts, my feelings, these feelings, those feelings... I would say

that thought makes what is often called in modern language a system.

A system means a set of connected things or parts. But the way people

commonly use the word nowadays it means something all of whose parts

are mutually interdependent - not only for their mutual action, but for

their meaning and for their existence. A corporation is organized as a

system - it has this department, that department, that department. They

don't have any meaning separately; they only can function together. And

also the body is a system. Society is a system in some sense. And so

on. Similarly, thought is a system. That system not only includes

thoughts, "felts" and feelings, but it includes the state of the body;

it includes the whole of society - as thought is passing back and forth

between people in a process by which thought evolved from ancient

times. A system is constantly engaged in a process of development,

change, evolution and structure changes... although there are certain

features of the system which become relatively fixed. We call this the structure....

Thought has been constantly evolving and we can't say when that

structure began. But with the growth of civilization it has developed a

great deal. It was probably very simple thought before civilization,

and now it has become very complex and ramified and has much more

incoherence than before. Now, I say that this system has a fault in it

- a "systematic fault". It is not a fault here, there or here, but it

is a fault that is all throughout the system. Can you picture that? It

is everywhere and nowhere. You may say "I see a problem here, so I will

bring my thoughts to bear on this problem". But "my" thought is part of

the system. It has the same fault as the fault I'm trying to look at,

or a similar fault. Thought is constantly creating problems that way

and then trying to solve them. But as it tries to solve them it makes

it worse because it doesn’t notice that it's creating them, and the

more it thinks, the more problems it creates. To address societal problems during his later years, Bohm wrote a proposal for a solution that has become known as "

Bohm Dialogue", in which equal status and "free space" form the most important prerequisites of communication and the appreciation of differing personal beliefs. He suggested that if these Dialogue groups were

experienced on a sufficiently wide scale, they could help overcome the

isolation and fragmentation Bohm observed was inherent in society. Bohm continued his work in quantum physics past his retirement in 1987. His final work, the posthumously published The Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory (1993), resulted from a decades long collaboration with his colleague Basil Hiley.

He also spoke to audiences across Europe and North America on the

importance of dialogue as a form of sociotherapy, a concept he borrowed

from London psychiatrist and practitioner of Group Analysis Patrick De Mare, and had a series of meetings with the Dalai Lama. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1990. Near

the end of his life, Bohm began to experience a recurrence of

depression which he had suffered at earlier times in his life. He was admitted to the Maudsley Hospital in South London on 10 May 1991. His condition worsened and it was decided that the only treatment that might help him was electroconvulsive therapy.

Bohm's wife consulted psychiatrist David Shainberg, Bohm's long time

friend and collaborator, who agreed that electroconvulsive treatments

were probably his only option. Bohm showed improvement from the

treatments and was released on 29 August. However, his depression

returned and was treated with medication. David Bohm died of a heart failure in Hendon, London,

on 27 October 1992, aged 74. He had been traveling in a London taxicab

on that day; after not getting any response from the passenger in the

back seat for a few seconds, the driver turned back and found that Dr.

Bohm had died. David Bohm was widely considered one of the best quantum physicists of all time.