<Back to Index>

- Physicist Johann Christian Poggendorff, 1796

- Painter Albert Lee Tucker, 1914

- Empress and Autocrat of All the Russias Elizaveta Petrovna, 1709

PAGE SPONSOR

Albert Lee Tucker (29 December 1914 – 23 October 1999), a pivotal Australian artist, was a member of the Heide Circle, a group of leading modernist artists and writers that centred on the art patrons John and Sunday Reed, whose home, "Heide", located in Bulleen, near Heidelberg (outside Melbourne), was a haven for the group. Tucker's major series Images of modern evil (1943 – 47) depicted prostitutes and soldiers in Melbourne.

Tucker loathed school and willingly left at 14 and became a commercial artist. He attended life drawing classes at the Victorian Artists Society where he honed his brilliant draughtsmanship.

Throughout

the 1930s, Tucker continued to refine his skills, while experimenting

with his homemade paints. In the late 1930s, two important émigré artists arrived in Melbourne –

Josl Bergner and Danila Vassilieff. Their realistic representations had

a great effect on Tucker’s work, as he too, began to explore

confronting truths of the depression. However, Tucker’s work began to

take more shape in the next decade, the “Angry Decade” of the 1940s, as

the artists responded to the horror of war, incensed by the abolition

of hope just after the depression appeared to be clearing up. Tucker's perceptive response to the world around him was recognised by two people - Sunday and John Reed. These two saw connections between Tucker's work and other artists, angry too at the social situation. Sunday

and John Reed were members of the Contemporary Arts Society, set up to

promote these emerging artists, known as the modernists. The Society

was set up in 1938 by George Bell,

in opposition to the government Australian Academy of Art, which was

believed to promote conservative art and not the modernists. The modernists included Albert Tucker, Joy Hester, Sidney Nolan, John Perceval, Arthur Boyd and Noel Counihan.

These artists met to discuss material on a regular basis. Tucker

enjoyed being part of what he saw as a like minded group of artists,

all focused on producing works along similar themes, in response to

war, depression and moral degradation. The artists also brought

influences from European movements such as Surrealism, Cubism, Expressionism, Dadaism and Constructivism. From this "Angry" group of modernists, formed a group known as the Angry Penguins, which also included many social realists. The modernists and social realists shared

the same concerns, and their work became focused on war and its

horrors, along with moral decay and the emergence of Americanism. The Angry Penguins was also a publication that these artists wrote for, published by Max Harris. Tucker’s original influences, Bergner and Vassilieff, were part of this group. The Angry Penguins was the major outlet for the expression of avant - garde ideas. In

1941, Tucker married fellow artist Joy Hester, and they had a son,

Sweeney. It emerged many years later that Tucker was not the boy's

biological father — it was probably Australian jazz drummer Billy Hyde, with whom Hester had had a brief affair. When Hester was later diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma,

she gave Sweeney into the care of the Reeds, who adopted him. Joy

Hester died in 1960, and in 1964 Tucker married Barbara Bilcock.

Sweeney committed suicide in 1979. Tucker's main inspirations can be divided into periods, although he was originally influenced by the depression, post - impressionists, expressionists and social realists, also keeping in mind his involvement with the Angry Penguins, and his responses to war. Tucker's

first significant works were produced during his involvement in the

army. In 1940, Tucker was called up for army service and spent most of

his time working in Heidelberg Military Hospital drawing patients

suffering from horrific wounds and mental illnesses as a result of war.

He produced three important works at this stage, Man at Table, a pen

and ink illustration of a man whose nose had been sliced off by a shell

fragment, The Waste Land, an image of death sitting on a stool watching

and waiting, and Floating Figures, of two figures floating down a hall,

a third with a demented smile. All of these images illustrated the

horror and madness of war. At this time, Tucker was influenced by raw

images of death and horror, wishing to present a blunt, direct,

succinct image of war’s consequences. This is similar to the way social

realists wish to present their messages, although Tucker’s actual

delivery was surrealistic and expressionistic in appearance. In

1942, Tucker was discharged from the war and returned to a Melbourne he

did not like. He was particularly disgusted, but inspired by scenes of

Melbourne’s nightlife, of a city he felt demonstrated a collapse of

simple morality. He was shocked and outraged by images of schoolgirls

trotting home to reappear wearing skimpy miniskirts made from Union

Jacks and American flags, ready for a wild night in St. Kilda with the drunken American and Australian soldiers. In response he painted Victory Girls,

an impression of American soldiers, pig - like, grinning and clutching

the meager frames of young women in bawdy red lipstick, as if

possessions or prizes of war, representing a clear confusion as to what

war actually reaps. This painting was the catalyst for his series of

works known as the Images of Modern Evil, all depicting similar

nightlife and exploitation of women figures, or comodification of sex,

symbolized in recurring motifs; sticks or skin - toned blobs with red

smiles and single, elaborately styled eyes with curly lashes. As Tucker

continues creating these images, the subjects become less and less

human and occupy space in more and more disconnected ways; floating or

melting, being abducted from above, slumped on the side of the road,

lying in the shadows of movie theaters. His source is clear, after

seeing immoral scenes of sex, abduction, confusion and clear gender

stereotyping, and maintains the same surreal, expressionistic delivery

with socially realistic content. The

post - war period did not bring peace to visions at first he had hoped

for, explaining humanity's status after war as “irreparably damaged”,

viewing the world with great anxiety and a loss of hope. In early 1947,

Tucker traveled to Japan with the Australian army as an art

correspondent, required to interpret the devastation he saw there. He

produced a monochrome pen drawing called Hiroshima; it contains no

figures, just the aftermath of complete devastation, with somber tents

and shelters littering the landscape. During this time, Tucker was

influenced by his sense of hopelessness after seeing the war,

depression, and the fact that society had never improved. Upon

returning, he broke up with Joy Hester in 1945. Out of bitterness,

Tucker left for Europe later in 1947 for the next 13 years. In England

and Europe until 1958, Tucker painted many prostitutes, highly

influenced by the fact that no city seemed to be free of this “disease”

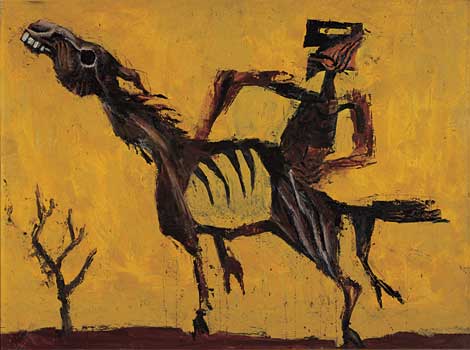

of prostitution, and so painted them in abundance. He then moved to New York in 1958 and his subjects switched from the city to outback Australia, feeling rather homesick. Where some works of Sidney Nolan and Russell Drysdale had

reached international level, Tucker rejected them as being

nationalistic. He depicted the landscape as being a harsh, barren and

sterile wasteland. He distorted stereotypes and icons of the Australian

bush, including convicts, Burke and Wills and the Kelly Gang.

He was influenced by the sheer barrenness and hopelessness that the

outback conveyed, and added these icons as pawns to the outback’s

deadly game. Throughout

the 1960s, Tucker began to face many personal traumas. He had begun to

form a good relationship with his son, Sweeny, who had been adopted by

Sunday and John Reed, but unfortunately he committed suicide in 1979. A

few years later, the Reeds both died within a week of each other. He

began to feel that many of the people he had influenced in his life

were quickly slipping away from him, looking back at Joy Hester, who

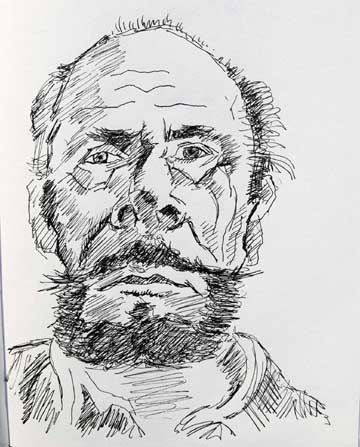

had also died in 1960. As a tribute, and to immortalise his

contemporaries, he produced the "Series of Faces I have met". The

series saw Tucker move away from his most celebrated themes, and to

variations of the Antipodean Head, a representation of an explorer’s

conflict with the environment that eventually fuses the two together to

become of the same element, as both the landscape and the heads were

created using the same medium, texture and colour. His other major

subjects were the “intruders” or “fauns” that became mindless metallic

beings that patrolled dead environments with guns and weaponry. This

added to his recurring themes of hopelessness and loss. Tucker's

style, subjects and attitude stay the same throughout his life as an

artist. His attitude always comes across as perceptive, pessimistic,

disgusted and generally critical of the environment around him.

Whenever he portrays males or females together, they seem to be

sexually confused – the females maintain an extreme prostitute image

and the males appear lustful and greedy. He often depicts scenes of

madness, destruction and horror especially in response to the war. He

portrays many scenes of hopelessness in his post - war stage, of the

desert, Hiroshima and of his personal losses. His

style retains a surreal, expressionistic quality. He often places

subjects on barren, dream like and hostile plains, with confused or

distorted bodies, appearing surrealistic. He enjoys disfiguring his

subjects’ forms to emphasise an issue or point, whilst being very

expressive in his appliance of mediums, linking to expressionism. His

messages however are ultimately of social realist quality, apart from

his surreal explorations into his losses in his final artistic stage.

He always wants to bluntly and confrontingly display social issues that

are harsh, but real and very much a part of society. Tucker's

subjects often recur. He starts with many psychologically disturbed

subjects in his war period, and also wounded subjects. He then moves to

a subject of modern evil, with the recurring motif of the fake smile,

single eye and pole and/or blob - like masses for bodies, with pig - like

males. His subjects then move to hopelessness and loss in the post - war

period, including the desert, Australian icons, Antipodean Heads,

“Fauns” and Hiroshima. The theme linking all of these is often moral

confusion.''