<Back to Index>

- Jurist Edward Coke, 1552

- Humanist Scholar and Poet Conrad Celtes, 1459

- Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia Milan Hodža, 1878

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Edward Coke (pronounced "Cook") (1 February 1552 – 3 September 1634) was a seventeenth century English jurist and Member of Parliament whose writings on the common law were the definitive legal texts for nearly 150 years. Born into a family of minor Norfolk gentry, Coke travelled to London as a young man to make his living as a barrister. There he rapidly gained prominence as one of the leading attorneys of his time, eventually being appointed Solicitor General and then Attorney General by Queen Elizabeth. As Attorney General, Coke famously prosecuted Sir Walter Raleigh and the Gunpowder Plot conspirators for treason. In 1606, Coke was made Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, later being elevated, in 1613, to Lord Chief Justice of England. As a judge, Coke delivered numerous important decisions, and he gained a reputation as the greatest jurist of his age. Nonetheless, his unwillingness to compromise in the face of challenges to the supremacy of the common law made him increasingly unpopular with James I, and he was eventually removed as Lord Chief Justice in 1616. Despite his dismissal from the bench and his already advanced age, Coke remained an influential political figure, leading parliamentary opposition to the Crown in the 1620s. His career in parliament culminated in 1628 when he acted as one of the primary authors of the Petition of Right. This document defined the rights of Englishmen and prevented the Crown from infringing them.

Coke's

enduring fame and importance rests principally on his immensely

influential legal writings and on his staunch defence of the rule of law in the face of royal absolutism.

His legal texts formed the basis for the modern common law, with

lawyers in both England and America learning their law from his Institutes and Reports until

the end of the eighteenth century. As a judge and Member of Parliament,

Coke supported individual liberty against arbitrary government and

sought to ensure that the king's authority was circumscribed by law. In

later times, both English reformers and American Patriots, such as John Lilburne, James Otis, and John Adams, used Coke's writings to support their conceptions of inviolable civil liberties. Sir Edward Coke was born at Mileham, Norfolk, the son of a barrister from a Norfolk family. He was educated at Norwich School and then, from 1567 to 1570, Trinity College, Cambridge, which he left without taking a degree. In 1571 he travelled to London to begin his legal education, enrolling first at Clifford's Inn before transferring, in 1572, to the Inner Temple.

On 20 April 1578, Coke was called to the bar. He argued his first case

before the Court of King's Bench in 1579, and in 1581 won his first

landmark case, Shelley's Case (from whence derives the famous "Rule in Shelley's Case"). During the 1580s and 1590s Coke's practice grew rapidly and he became one of the most prominent lawyers in England. His growing legal reputation was accompanied by increasing political power: in 1586 he was made a Justice of the Peace for Norfolk, became Solicitor General in 1592, Speaker of the House of Commons in 1593, and Attorney General in 1594, a post for which he was in competition with his rival Sir Francis Bacon. Coke's tenure as Attorney General was marked by his zealous prosecutions for treason of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (in 1601), Sir Walter Raleigh (in 1603) and the Gunpowder Plot conspirators (in 1606). During this period, Coke became fabulously wealthy, eventually coming to own 105 properties. It was also at this time that he began to publish his famous Reports (first volume printed 1600). On 30 June 1606, Coke was appointed Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas.

His tenure on the bench was marked by brilliant and innovative

judgments in a number of areas of the law, as well as by jurisdictional

conflict between the common law courts and the courts of Chancery, High Commission, and Admiralty. Coke's efforts to limit the jurisdictions of these courts through the issuance of writs of prohibition ultimately caused James I to

become involved in the conflict, and to assert a claim that he could

decide disputes between his different courts, and even judge individual

cases himself. To this Coke famously responded that: the

King in his own person cannot adjudge any case, either criminall ... or

betwixt party and party ... but this ought to be determined and

adjudged in some Court of Justice, according to the Law and Custom of

England.... Then the King said, that he thought the Law was founded

upon reason, and that he and others had reason, as well as the Judges:

To which it was answered by me, that true it was, that God had endowed

his Majesty with excellent Science, and great endowments of nature; but

his Majesty was not learned in the Lawes of his Realm of England, and

causes which concern the life, or inheritance, or goods, or fortunes of

his Subjects; they are not to be decided by naturall reason but by the

artificiall reason and judgment of Law, which Law is an act which

requires long study and experience, before that a man can attain to the

cognizance of it; And that the Law was the Golden metwand and measure

to try the Causes of the Subjects; and which protected his Majesty in

safety and peace. In 1613, Coke was advanced to the position of Chief Justice of the King's Bench.

Although technically a promotion, this move was widely seen as a form

of chastisement for Coke, since the chief - justiceship of the Common

Pleas was a much more lucrative position. It was also hoped by the

king's councilors that the nominal promotion would make Coke more

tractable and amenable to the Crown's positions on cases. The

move failed to produce the desired results, however, as Coke continued

to quarrel with the non common law courts and to resist James' efforts

to meddle with cases or obtain favour from the judges. Ultimately,

Coke's unwillingness to submit to royal interference in the course of

the law was to be his downfall. The situation came to a head in The case of commendams (1616),

when James ordered the justices of the King's Bench to stay proceedings

in the case until they had consulted him. When the judges refused to

comply, James summoned them before the Privy Council and

asked them individually whether they would obey his command. All of the

judges submitted except Coke, who replied only that "he would do that

should be fit for a judge to do." As a result, Coke was removed from the chief justiceship on 16 November 1616. Coke

soon managed to obtain a return to royal favour by arranging the

marriage of his daughter, Frances, to Sir John Villiers, brother of the

king's favorite, the Earl of Buckingham.

The marriage resulted in Coke being made a Privy Councillor on 28

September 1617, although he was never restored to judicial office. His

return to favour did not last long, however. Coke was elected to parliament in 1621 for the borough of Liskeard, and soon became a leader of parliamentary opposition to the Crown. In 1621 he led the assault on monopolies, which at that time meant a government granted legal prohibition on attempts to compete with the monopoly holder, reintroducing impeachment (which had not been used since 1450) as a parliamentary weapon against governmental misconduct. Among those impeached and convicted was Coke's long time enemy, the Lord Chancellor Sir Francis Bacon. For his opposition, Coke was removed from the Privy Council and imprisoned in the Tower of London for much of 1622. In 1624 he was again returned to parliament, this time for Coventry, where he continued his assaults on monopolies and led the parliamentary faction seeking war with Spain. And in 1625, as a Knight of the Shire for Norfolk, he attacked the prodigality of the Court and its connections to Arminianism. As a result of his continued opposition, Coke was prevented from being elected to the Parliament of 1626 by Charles I, who pricked him to serve as High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire, an office which required him to stay in that county. Coke's

parliamentary career culminated with the Parliament of 1628, in which

he played probably his most important role. The Parliament of 1628

assembled at a time in which civil liberties were widely seen to be

under threat from absolutism. In particular, Charles' recent practice

of imprisoning subjects without cause shown, levying taxes without

parliamentary consent, billeting soldiers, and imposing martial law in time of peace raised fears that the laws of

the kingdom were being subverted. Coke led the effort to pass

legislation guaranteeing fundamental English liberties, being the first

MP to present a bill on the subject. He

deployed his immense legal knowledge to provide precedents to back up

claims to specific fundamental liberties, and his personal legal

authority helped to convince others that Charles' actions had been

contrary to law. The culmination of his efforts was the famous Petition of Right,

of which Coke was one of the primary authors. The Petition of Right

declared that the king could not imprison his subjects without cause,

that the legitimacy of imprisonment must be challengeable by habeas corpus,

that taxation must be by parliament, that billeting was illegal, and

that martial law could not be imposed in time of peace. It is a

fundamental document of the English constitution. Despite promoting English liberties, Coke did little to improve the rights and liberties of women. In

fact, Coke was alleged to have kidnapped and beaten his daughter,

Frances, to force her into marrying Sir John Villiers, and upon his

death, his widow remarked: "We shall never see his like again, praises

be to God." Already

76 years old in 1628, Coke retired to his home at Stoke Pages,

Buckinghamshire, at the end of the parliamentary session. He spent much

of his remaining years engaged in finishing his monumental four volume Institutes of the Lawes of England. In 1632, Charles I, worried that Coke's legal writings might prove politically dangerous, ordered his papers seized. Coke died on 3 September 1634.

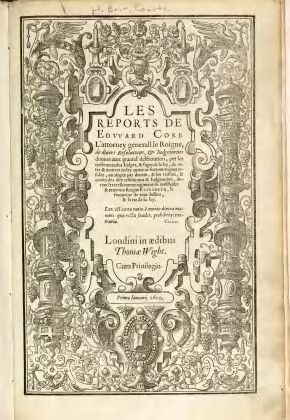

Coke's

reputation as one of the most influential jurists in Anglo - American

history rests to a significant extent on the central role that his

legal writings have had in the development of the modern common law. Of

greatest importance have been his thirteen volume series of Reports, and his four volume Institutes of the Lawes of England. Coke's Reports have been described by the legal historian Sir John Baker as "perhaps the single most influential series of named reports." They

are the earliest reports still commonly cited by lawyers today and due

to their singular importance have the distinction of being cited as

simply The Reports. Coke

edited and published eleven volumes during his own lifetime, while two

volumes, containing many of his most politically sensitive decisions,

were not published until the Interregnum. His Reports contain

cases spanning in time from his student days to 1616, the year that he

was removed as Chief Justice of the King's Bench. Most of the reports

after 1606 record Coke's own decisions as judge; prior to that, the

reported cases are mostly those that he took part in as an attorney.

Coke, however, had a noted tendency to include his own justifications

for the decisions along with (or instead of) those of the judges who

made them, meaning that many of the early cases reflect his own

interpretation of the law. Although this was known at the time, "Coke's

personal authority was enough to justify this method." From their first publication, Coke's Reports have

had an immense influence. Produced at a time when printed reports

discussing substantive law (as opposed to pleading) were almost

non-existent, the Reports set

down for the first time many of the fundamental principles of the

common law. Even Coke's enemy, Sir Francis Bacon, wrote praisingly of

the Reports: Had it not been for Sir Edward Coke's Reports (which

though they may have errors, and some peremptory and extrajudicial

resolutions more than are warranted, yet they contain infinite good

decisions and rulings over of cases), for the law by this time had been

almost like a ship without ballast; for that the cases of modern

experience are fled from those that are adjudged and ruled in former

time." Even

today, the foundations of the law of real property, tort, and contract,

and administrative, environmental, and corporations law are traced to Coke's Reports. The Reports were

also important in the development of early American constitutional

theory: many of the individual reports emphasised the importance of the

rule of law and due process, and helped to popularise in America a

notion of inviolable rights that were the inheritance of Englishmen. In

particular, Coke's decision in Dr. Bonham's Case has been cited as the origin of the concept of judicial review, which was adopted in the United States by Marbury v. Madison.

The case was also routinely pointed to in the Revolutionary period as

demonstrating that there were specific fundamental rights that

Parliament could not infringe. The Institutes of the Lawes of England are a four volume survey of much of the common law as it stood in the early seventeenth century. Like the Reports, they have been extremely influential in the development of the common law. The four volumes of the Institutes address property law, statutes, pleas of the crown, and the jurisdiction of courts, respectively. The first volume, A Commentary on Littleton, often referred to as Coke on Littleton,

has been perhaps the most important of the four to the development of

the common law, serving as the primary textbook on property law until

the nineteenth century. It was the only one of the Institutes published

during Coke's lifetime - the other three were suppressed by Charles I

due to the politically dangerous material they contained, and were not

published until the English Civil War. The Second Institute contains Coke's very influential gloss on Magna Carta,

in which he propounded the view that the Charter guaranteed substantive

rights to all Englishmen and acted as a strict limitation on the power

of the Crown. Coke's expansive interpretation of Magna Carta would

provide inspiration to later political groups such as the Levellers and the American Revolutionaries. Like virtually all of Coke's writings, the Institutes are written in a particularly difficult and disorganised style. The great English legal writer Sir William Blackstone declared them to be "greatly defective in method," and it is said that the young Joseph Story broke down in tears after trying to work his way through Coke on Littleton. Nevertheless, Blackstone praised the Institutes as a "valuable mine of common law learning," and the information they (and the Reports) contained formed the basis for much of his own famous Commentaries. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Institutes served as the primary textbooks for law students. They were particularly important in the American Colonies, where they were

read by "virtually every student of the law" and were highly influential in shaping the nascent American law. Thomas Jefferson, for example, wrote that during his days as a law student (1762 – 1767) "Coke Lyttleton was the universal elementary book of law students," and John Rutledge remarked that the Institutes seemed "to be almost the foundation of our law." Today, the Institutes remain

a point of first reference for lawyers seeking to discover the state of

the law in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, and they have been

cited in numerous United States Supreme Court opinions, including notably Roe v. Wade.