<Back to Index>

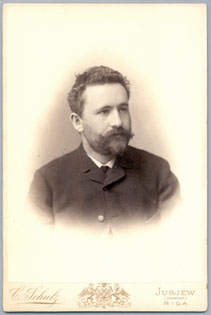

- Psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, 1856

- Writer and 1st President of the International Olympic Committee Demetrios Vikelas, 1835

- Viceroy of the Qing Empire Li Hongzhang, 1823

PAGE SPONSOR

Emil Kraepelin (Neustrelitz, 15 February 1856 – 7 October 1926, Munich) was a German psychiatrist. H.J. Eysenck's Encyclopedia of Psychology identifies him as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, as well as of psychopharmacology and psychiatric genetics. Kraepelin believed the chief origin of psychiatric disease to be biological and genetic malfunction. However, Kraepelin was criticized for considering schizophrenia as a biological illness in the absence of any detectable histologic or anatomic abnormalities. While Kraepelin tried to find organic causes of mental illness, he adopted many theses of positivist medicine, but the basis for understanding is not etiology, as the causes of madness cannot be established with any precision. His theories dominated psychiatry at the start of the twentieth century and, despite later psychodynamic incursions by Sigmund Freud and his disciples, appeared to enjoy a revival at century's end.

Kraepelin, the son of a civil servant, was born in 1856 in Neustrelitz, in the Mecklenburg district of Germany. He was first introduced to biology by his brother Karl, 10 years older and, later, the director of the Zoological Museum of Hamburg.

Kraepelin began his medical studies at 18, in Leipzig and Wurzburg, Germany. At Leipzig, where he studied neuropathology under Paul Flechsig and experimental psychology with Wilhelm Wundt, he wrote a prize winning essay, "The Influence of Acute Illness in the Causation of Mental Disorders." He received his M.D. in 1878. In 1879, Kraepelin went to work with Bernhard von Gudden at the University of Munich, where he completed his thesis, "The Place of Psychology in Psychiatry". Returning to the University of Leipzig in 1882, he worked in Wilhelm Heinrich Erb's neurology clinic and in Wundt's psychopharmacology laboratory. His major work, "Compendium der Psychiatrie", was first published in 1883. In it, he argued that psychiatry was a branch of medical science and should be investigated by observation and experimentation like the other natural sciences. He called for research into the physical causes of mental illness and established the foundations of the modern classification system for mental disorders. Kraepelin proposed that by studying case histories and identifying specific disorders, the progression of mental illness could be predicted, after taking into account individual differences in personality and patient age at the onset of disease.

In

1884 he became senior physician in Leubus and the following year he was

appointed director of the Treatment and Nursing Institute in Dresden.

In 1886, at the age of 30, Kraepelin was named professor of psychiatry

at the University of Dorpat (later the University of Tartu) in what is today Estonia. Four years later, he became department head at the

University of Heidelberg, where he remained until 1904. Whilst at

Dorpat he became the director of the eighty bed University Clinic.

There he began to study and record many clinical histories in detail

and "was led to consider the importance of the course of the illness

with regard to the classification of mental disorders." Ten years later

he announced that he had found a new way of looking at mental illness.

He referred to the traditional view as "symptomatic" and to his view as

"clinical". This turned out to be his paradigm setting synthesis of the

hundreds of mental disorders classified by the 19th century, grouping

diseases together based on classification of syndromes — common patterns of

symptoms — rather than by simple similarity of major symptoms in the

manner of his predecessors. In fact, it was precisely because of the

demonstrated inadequacy of such methods that Kraepelin developed his

new diagnostic system. Kraepelin is specifically credited with the classification of what was previously considered to be a unitary concept of psychosis, into two distinct forms: manic depression (now seen as comprising a range of mood disorders such as recurrent major depression and bipolar disorder), and dementia praecox. Drawing on his long term research, and using the criteria of course, outcome and prognosis, he developed the concept of dementia praecox,

which he defined as the "sub - acute development of a peculiar simple

condition of mental weakness occurring at a youthful age." When he

first introduced this concept as a diagnostic entity in the fourth

German edition of his Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie in 1893, it was placed among the degenerative disorders alongside, but separate from, catatonia and dementia paranoides. At that time, the concept corresponded by and large with Ewald Hecker's hebephrenia. In the sixth edition of the Lehrbuch in 1899 all three of these clinical types are treated as different expressions of one disease, dementia praecox. One

of the cardinal principles of his method was the recognition that any

given symptom may appear in virtually any one of these disorders; e.g.,

there is almost no single symptom occurring in dementia praecox which

cannot sometimes be found in manic depression. What distinguishes each

disease symptomatically (as opposed to the underlying pathology) is not

any particular (pathognomonic) symptom or symptoms, but a specific

pattern of symptoms. In the absence of a direct physiological or genetic test or marker for each disease, it is only possible to

distinguish them by their specific pattern of symptoms. Thus,

Kraepelin's system is a method for pattern recognition, not grouping by

common symptoms. Kraepelin

also demonstrated specific patterns in the genetics of these disorders

and specific and characteristic patterns in their course and outcome.

Generally speaking, there tend to be more schizophrenics among the

relatives of schizophrenic patients than in the general population,

while manic depression is more frequent in the relatives of

manic depressives. Though, of course, this does not demonstrate genetic

linkage, as this might be a socio - environmental factor as well. He

also reported a pattern to the course and outcome of these conditions.

Kraepelin believed that schizophrenia had a deteriorating course in

which mental function continuously (although perhaps erratically)

declines, while manic depressive patients experienced a course of

illness which was intermittent, where patients were relatively

symptom free during the intervals which separate acute episodes. This

led Kraepelin to name what we now know as schizophrenia, dementia

praecox (the dementia part

signifying the irreversible mental decline). It later became clear that

dementia praecox did not necessarily lead to mental decline and was

thus renamed schizophrenia by Eugen Bleuler to correct Kraepelin's misnomer.

Kraepelin

postulated that there is a specific brain or other biological pathology

underlying each of the major psychiatric disorders. As a colleague of Alois Alzheimer, and co-discoverer of Alzheimer's disease,

it was his laboratory which discovered its pathologic basis. Kraepelin

was confident that it would someday be possible to identify the

pathologic basis of each of the major psychiatric disorders.

Kraepelin's

great contribution in classifying schizophrenia and manic depression

remains relatively unknown to the general public, and his work, which

had neither the literary quality nor paradigmatic power of Freud's, is

little read outside scholarly circles. Kraepelin's

contributions were to a good extent marginalized throughout a good part

of the twentieth century, during the success of Freudian etiological

theories. However, his views now dominate psychiatric research and

academic psychiatry, and today the published literature in the field of

psychiatry is overwhelmingly biological in its orientation. His

fundamental theories on the etiology and diagnosis of psychiatric

disorders form the basis of all major diagnostic systems in use today,

especially the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-IV and the World Health Organization's ICD system.

In that sense, not only is Kraepelin's significance historical, but

contemporary psychiatric research is also heavily influenced by his

work. Kraepelin, being a disciple of Wilhem Wundt, had a life long interest in experimental psychology. In the Heidelberg and early Munich years he edited Psychologische Arbeiten,

a journal on experimental psychology. One of his own famous

contributions to this journal also appeared in the form of a monograph

(105 p.) entitled Über Sprachstörungen im Traume (on language disturbances in dreams). Kraepelin, on the basis on the dream - psychosis analogy, studied for more than 20 years language disorder in dreams in order to study indirectly schizophasia. The

dreams Kraepelin collected are mainly his own. They lack extensive

comment by the dreamer. In order to study them the full range of

biographical knowledge available today on Kraepelin is necessary.

He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1908.