<Back to Index>

- Philologist Issac Casaubon, 1559

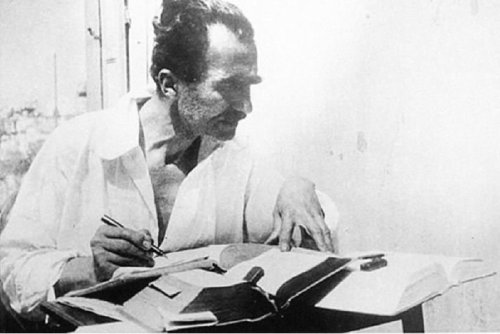

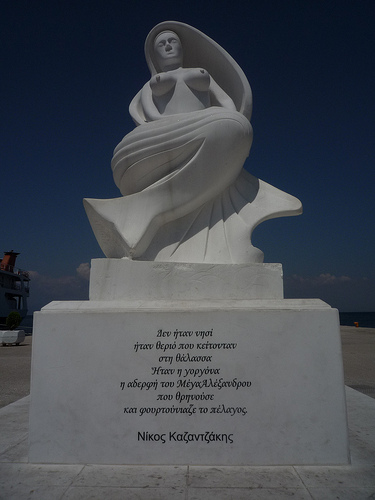

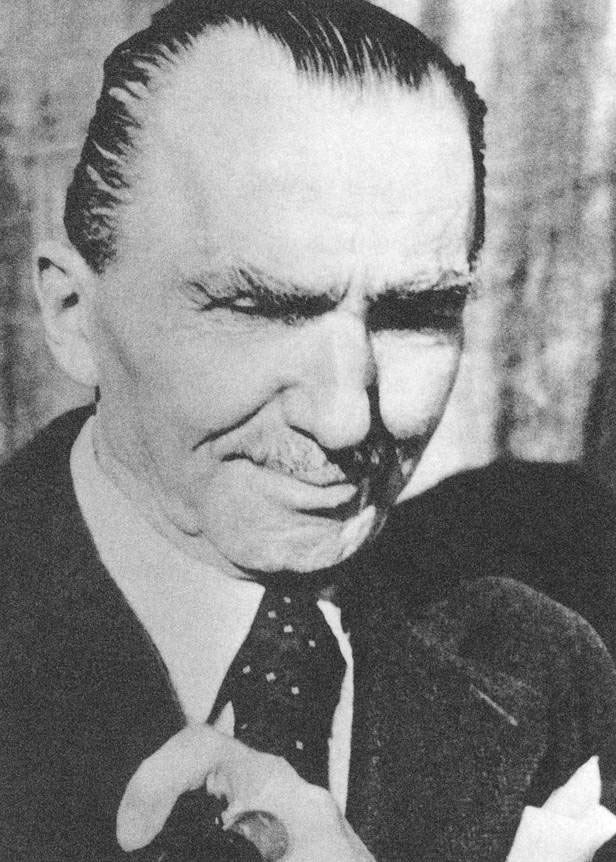

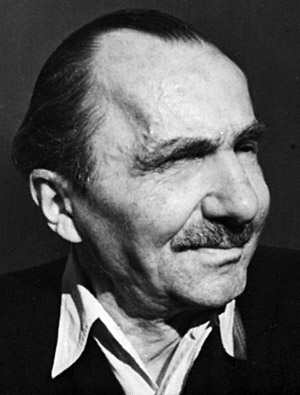

- Writer Nikos Kazantzakis, 1883

- Lord High Steward of Sweden Per Brahe the Younger, 1602

PAGE SPONSOR

Nikos Kazantzakis (Greek: Νίκος Καζαντζάκης) (February 18, 1883, Heraklion, Crete, Ottoman Empire - October 26, 1957, Freiburg, Germany) was arguably the most important Greek writer and philosopher of the 20th century, celebrated for his novel Zorba the Greek, considered his magnum opus. He did not become well known globally until the 1964 release of the Michael Cacoyannis film Zorba the Greek, based on the novel of the same title.

When Kazantzakis was born, Crete was still under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. His surname, Kazantzakis, derives from a Turkish word Kazancı as in Kazantzidis. Kazan means a cauldron in Turkish and -cı is an agent suffix similar to "-er" in English. Thus, Kazancı means someone who produces, repairs, and/or sells cauldrons. The last part of Kazantzakis' name i.e. "-akis" is specific to Crete and is the Cretan equivalent to the '-son' surname suffix means the "son of" similar to a name ending in "-son" in English e.g. Johnson. Thus "kazantzakis" literally means the son of someone who produces, repairs, and/or sells cauldrons.

From 1902 Kazantzakis studied law at the University of Athens, then went to Paris in 1907 to study philosophy. Here he fell under the influence of Henri Bergson. Upon his return to Greece, he began translating works of philosophy. In 1914 he met Angelos Sikelianos. Together they travelled for two years in places where Greek Orthodox

Christian culture flourished, largely influenced by the enthusiastic

nationalism of Sikelianos. Kazantzakis

married Galatea Alexiou in 1911; they divorced in 1926. He married

Eleni Samiou in 1945. Between 1922 and his death in 1957, he sojourned

in Paris and Berlin (from 1922 to 1924), Italy, Russia (in 1925), Spain (in 1932), and then later in Cyprus, Aegina, Egypt, Mount Sinai, Czechoslovakia, Nice (he later bought a villa in nearby Antibes, in the Old Town section near the famed seawall), China, and Japan. While in Berlin, where the political situation was explosive, Kazantzakis discovered communism and became an admirer of Lenin. He never became a consistent communist, but visited the Soviet Union and stayed with the Left Opposition politician and writer Victor Serge. He witnessed the rise of Joseph Stalin,

and became disillusioned with Soviet style communism. Around this time,

his earlier nationalist beliefs were gradually replaced by a more

universal ideology. In

1945, he became the leader of a small party of the non - communist left,

and entered the Greek government as Minister without Portfolio. He

resigned this post the following year. In 1946, The Society of Greek

Writers recommended that Kazantzakis and Angelos Sikelianos be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 1957, he lost the Prize to Albert Camus by

one vote. Camus later said that Kazantzakis deserved the honour "a

hundred times more" than himself. Late in 1957, even though suffering

from leukemia, he set out on one last trip to China and Japan. Falling

ill on his return flight, he was transferred to Freiburg, Germany, where he died. He is buried on the wall surrounding the city of Heraklion near the Chania Gate, because the Orthodox Church ruled

out his being buried in a cemetery. His epitaph reads "I hope for

nothing. I fear nothing. I am free." (Δεν ελπίζω τίποτα. Δε φοβάμαι

τίποτα. Είμαι λέφτερος.) The

50th anniversary of the death of Nikos Kazantzakis was selected as main

motif for a high value euro collectors' coins; the €10 Greek Nikos Kazantzakis commemorative coin, minted in 2007. His image is shown in the obverse of the coin, while on the reverse the National Emblem of Greece with his signature is depicted. His first work was the 1906 narrative Serpent and Lily (Όφις και Κρίνο), which he signed with the pen name Karma Nirvami. In 1909, Kazantzakis wrote a one - act play titled Comedy, which remarkably resonates existential themes

that become prevalent much later in Post - World War II Europe by writers

like Sartre and Camus. In 1910, after his studies in Paris, he wrote a

tragedy "The Master Builder" (Ο Πρωτομάστορας), based on a popular

Greek folkloric myth. Kazantzakis considered his huge epic poem (33,333

verses long) The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel to

be his most important work. Begun in 1924, he rewrote it seven times

before publishing it in 1938. According to another Greek author, Pantelis Prevelakis, "it has been a superhuman effort to record his immense spiritual experience." Following the structure of Homer's Odyssey, it is divided into 24 rhapsodies. His most famous novels include Zorba the Greek (1946, in Greek Βίος και Πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά); The Greek Passion (1948, UK title Christ Recrucified, in Greek Ο Χριστός Ξανασταυρώνεται); Captain Michalis (1950, UK title Freedom and Death, in Greek Καπετάν Μιχάλης); The Last Temptation of Christ (1951, Ο Τελευταίος Πειρασμός); and Saint Francis (1956, UK title God's Pauper: St. Francis of Assisi, in Greek Ο Φτωχούλης του Θεού). Report to Greco (1961,

Αναφορά στον Γκρέκο), containing both autobiographical and fictional

elements, summed up his philosophy as the "Cretan Glance." Starting

in his youth, Kazantzakis was spiritually restless. Tortured by

metaphysical and existential concerns, he sought relief in knowledge

and travel, contact with a diverse set of people, in every kind of

experience. The influence of Friedrich Nietzsche on his work is evident, especially Nietzsche's atheism and sympathy for the superman (Übermensch)

concept. However, he was also haunted by spiritual concerns. To attain

a union with God, Kazantzakis entered a monastery for six months. In

1927 Kazantzakis published in Greek his "Spiritual Exercises" (Greek:

"Ασκητική"), which he had composed in Berlin in 1923. The book was

translated into English and published in 1960 with the title The Saviors of God. The figure of Jesus was ever present in his thoughts, from his youth to his last years. The Christ of The Last Temptation of Christ shares Katzantzakis' anguished metaphysical and existential concerns, seeking

answers to haunting questions and often torn between his sense of duty

and mission, on one side, and his own human needs to enjoy life, to

love and to be loved, and to have a family. A tragic figure who at the

end sacrifices his own human hopes for a wider cause, Kazantzakis'

Christ is not an infallible, passionless deity but rather a passionate

and emotional human being who has been assigned a mission, with a

meaning that he is struggling to understand and that often requires him

to face his conscience and his emotions, and ultimately to sacrifice

his own life for its fulfilment. He is subject to doubts, fears and

even guilt. In the end he is the Son of Man, a man whose internal struggle represents that of humanity. Many Greek religious conservatives condemned Kazantzakis' work. His reply was: "You

gave me a curse, Holy fathers, I give you a blessing: may your

conscience be as clear as mine and may you be as moral and religious as

I" before the Greek Orthodox Church anathematized him in 1955. (Greek:"Μου

δώσατε μια κατάρα, Άγιοι πατέρες, σας δίνω κι εγώ μια ευχή: Σας εύχομαι

να ‘ναι η συνείδηση σας τόσο καθαρή, όσο είναι η δική μου και να ‘στε

τόσο ηθικοί και θρήσκοι όσο είμαι εγώ"). The Last Temptation was included by the Roman Catholic Church in the Index of Prohibited Books. Kazantzakis' reaction was to send a telegram to the Vatican quoting the Christian writer Tertullian: Ad tuum, Domine, tribunal appello ("I lodge my appeal at your tribunal, Lord", in Greek "Στο δικαστήριό σου ασκώ έφεση, ω Kύριε"). Many cinemas banned the Martin Scorsese film, which was released in 1988 and based on this novel. In

Kazantzakis' day, the international market for material published in

modern Greek was quite small. Kazantzakis also wrote in colloquial Demotic Greek,

with traces of Cretan dialect, which made his writings all the more

controversial in conservative literary circles at home. Translations of

his books into other European languages did not appear until his old

age. Hence he found it difficult to earn a living by writing, which led

him to write a great deal, including a large number of translations

from French, German, and English, and curiosities such as French

fiction and Greek primary school texts, mainly because he needed the

money. Some of this "popular" writing was nevertheless distinguished,

such as his books based on his extensive travels, which appeared in the

series "Travelling" (Ταξιδεύοντας) which he founded. These books on

Greece, Italy, Egypt, Sinai, Cyprus, Spain, Russia, Japan, China, and

England were masterpieces of Greek travel literature.