<Back to Index>

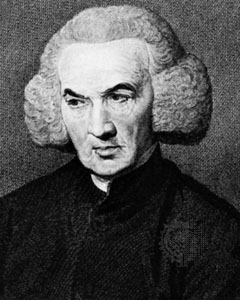

- Philosopher Richard Price, 1723

- Painter Kazimir Severinovich Malevich, 1879

- Mughal Emperor of India Zahir ud-din Muhammad Babur, 1483

PAGE SPONSOR

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher and preacher in the tradition of English Dissenters, and a political pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the American Revolution. He fostered connections between a large number of people, including writers of the Constitution of the United States. He spent most of his adult life as minister of Newington Green Unitarian Church, where possibly the congregant he most influenced was early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who extended his ideas on the egalitarianism inherent in the spirit of the French Revolution to encompass women's rights as well. In addition to his work as a moral and political philosopher, he also wrote on issues of statistics and finance, and was inducted into the Royal Society for these contributions.

Price was born in Wales, in Tynton in Glamorgan, the son of a dissenting minister. Educated privately and at a dissenting academy in London, he became chaplain and companion to a Mr Streatfield at Stoke Newington, then a village just north of London but now considered part of Inner London. Streatfield's death and that of an uncle in 1757 improved his circumstances, and on 16 June 1757 he married Sarah Blundell, originally of Belgrave in Leicestershire. The following year they moved to Newington Green, and took up residence in No. 54 the Green, in the middle of a terrace even then a hundred years old. (The building still survives as London's oldest brick terrace, dated 1658.)

In that house, or the church itself, he was visited by Founding Fathers of the United States such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Paine; other American politicians such as John Adams, who later became the second president of the United States, and his wife Abigail; British politicians such as Lord Lyttleton, the Earl of Shelburne, Earl Stanhope (known as "Citizen Stanhope"), and even the Prime Minister William Pitt; philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith; agitators such as prison reformer John Howard, gadfly John Horne Tooke, and husband and wife John and Ann Jebb, who between them campaigned on expansion of the franchise, opposition to the war with America, support for the French Revolution, abolitionism, and an end to legal discrimination against Roman Catholics; writers such as poet and banker Samuel Rogers; and clergyman - mathematician Thomas Bayes, of Bayes' theorem.

Price was fortunate in forming close friendships amongst his neighbours and congregants. One was Thomas Rogers, father of the above named Samuel Rogers, a merchant turned banker who had married into a long established Dissenting family and lived at No. 56 the Green. More than once, Price and the elder Rogers rode on horseback to Wales. Another was the Rev. James Burgh, author of The Dignity of Human Nature and Thoughts on Education, who opened his Dissenting Academy on the green in 1750 and sent his pupils to Price's sermons. Price, Rogers, and Burgh formed a dining club, eating at each other's houses in rotation.

And there were many at a distance who acknowledged their debt to Price, such as the Unitarian theologians William Ellery Channing and Theophilus Lindsey, and the formidable polymath and Dissenting clergyman, Joseph Priestley, discoverer of oxygen. When Priestley's support of dissent led to the riots named after him, he fled Birmingham and headed for the sanctuary of Newington Green, where Rogers took him in. Price and Priestley took the most opposite views on morals and metaphysics. In 1778 appeared a published correspondence between these two liberal theologians on the subjects of materialism and necessity, wherein Price maintains, in opposition to Priestley, the free agency of man and the unity and immateriality of the human soul.

It was illegal to deny the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, and this remained the case until the passage of the 1813 Act. Nonetheless, various theologians and clergymen had begun to voice non-Trinitarian views. Theophilus Lindsey resigned his living and moved to London to create an avowedly Unitarian congregation, and Price played a key role in finding and securing the premises for this, which became Essex Street Chapel. Both Price and Priestley were what would now vaguely be called "Unitarians", though they occupied respectively the extreme right and the extreme left position of that school. Indeed, Price's opinions would seem to have been rather Arian than Socinian.

In 1744 Price published a volume of sermons, which gained him the acquaintance of Lord Shelburne;

this raised his reputation and helped determine the direction of his

career. It was, however, as a writer on financial and political

questions that Price became widely known. In 1769, in a letter to Benjamin Franklin,

he wrote some observations on the expectation of lives, the increase of

mankind, and the population of London, which were published in the Philosophical Transactions of that year; in May 1770 he presented to the Royal Society a

paper on the proper method of calculating the values of contingent

reversions. The publication of these papers is said to have helped draw

attention to the inadequate calculations on which many insurance and

benefit societies had recently been formed. In 1769 Price received the

honorary degree of D.D. from the University of Glasgow. In 1771 he published his Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the National Debt (ed. 1772 and 1774). This pamphlet excited considerable controversy, and is supposed to have influenced William Pitt the Younger in re-establishing the sinking fund for the extinction of the national debt, created by Robert Walpole in 1716 and abolished in 1733. The means proposed for the extinction of the debt are described by Lord Overstone as "a sort of hocus - pocus machinery," supposed to work "without loss to any one," and consequently unsound. Price then turned his attention to the question of the American colonies. He had from the first been strongly opposed to the war, and in 1776 he published a pamphlet entitled Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government, and the Justice and Policy of the War with America.

Several thousand copies of this work were sold within a few days; a

cheap edition was soon issued; the pamphlet was extolled by one set of

politicians and abused by another; amongst its critics were Dr Markham, archbishop of York, John Wesley, and Edmund Burke; and Price rapidly became one of the best known men in England. He was presented with the freedom of the city of London, and it is said that his pamphlet had no inconsiderable share in determining the Americans to declare their independence. A second pamphlet on the war with America, the debts of Great Britain,

and kindred topics followed in the spring of 1777. His name thus became

identified with the cause of American independence. He was the intimate

friend of Franklin; he corresponded with Turgot;

and in the winter of 1778 he was invited by Congress to go to America

and assist in the financial administration of the states. This offer he

refused from unwillingness to quit his own country and his family

connections. In 1781 he, solely with George Washington, received the degree of Doctor of Laws from Yale College. The support Price gave to the revolt of the colonies of British North America made his name as a famous or notorious preacher. Price rejected traditional Christian notions of original sin and moral punishment, preaching the perfectibility of human nature, and he wrote on theological questions. However, his interests were wide ranging, and during the decades he spent as minister of NGUC, he also wrote on finance, economics, probability, and life insurance, being inducted into the Royal Society in recognition of his work. On the 101st anniversary of the Glorious Revolution, he preached a sermon entitled "A Discourse on the Love of our Country," thus igniting a so-called "pamphlet war" known as the Revolution Controversy, furiously debating the issues raised by the French Revolution. Burke's rebuttal "Reflections on the Revolution in France"

attacked Price, whose friends Paine and Wollstonecraft leapt into the

fray to defend their mentor. The reputation of Price for speaking

without fear of the government on these political and philosophical

matters drew huge crowds to the church, and were published and sold as pamphlets (i.e. publications easily printed and circulated). The pamphlets on the American War made Price famous. He preached to crowded congregations, and, when Lord Shelburne acceded to power, not only was he offered the post of private secretary to the

premier, but it is said that one of the paragraphs in the king's speech

was suggested by him and even inserted in his words. In 1786 Mrs Price

died. There were no children by the marriage, his own health was

failing, and the remainder of his life appears to have been clouded by

solitude and dejection. The progress of the French Revolution alone cheered him. On the 19 April 1791 he died, worn out with suffering and disease. Arguably the congregant Price most influenced was the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who moved her fledgling school for girls from Islington to the Green in 1784, with the help of a fairy godmother whose good auspices found her a house to rent and twenty students to fill it. Her patron – or matron – was the well - off Mrs Burgh, widow of Price's friend. The new arrival attended services at NGUC: she was a life - long Anglican,

but, in keeping with the church's and Price's ethos of logical enquiry

and individual conscience, believers of all kinds were welcomed without

any expectation of conversion. The

approach of these Rational Dissenters appealed to Wollstonecraft: they

were hard working, humane, critical but uncynical, and respectful

towards women, and in her hour of need proved kinder to her than her own family. Price is believed to have secretly helped her with money to go to Lisbon to

aid her dear friend Fanny Blood. She, an unmarried woman making her own

way in the world, was marginal to the dominant society in just the same

way that the Dissenters were. Wollstonecraft

was then a young schoolmistress, as yet unpublished, but Price saw

something in her worth fostering, and became a friend and mentor.

Through the minister she met the great humanitarian and radical

publisher Joseph Johnson,

who was to guide her career and serve as a father figure. The ideas

Wollstonecraft ingested from the sermons at NGUC pushed her towards a

political awakening. A couple of years after she had had to leave Newington Green, these seeds germinated into A Vindication of the Rights of Men, a response to Burke's denunciation of the French Revolution and attack on Price. In 1792 she published the work for which she is best remembered, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, in the spirit of rationalism extending Price's arguments about equality to women: Tomalin argues

that just as the Dissenters were "excluded as a class from education

and civil rights by a lazy minded majority", so too were women, and the

"character defects of both groups" could be attributed to this

discrimination. Price appears 14 times in William Godwin's diary, Wollstonecraft's later husband.

Much of Price's most important philosophical work was in the region of

ethics. The Review of the Principal Questions in Morals (1757,

3rd ed. revised 1787) contains his whole theory. It is divided into ten

chapters, the first of which, though a small part of the whole,

completes his demonstration of ethical theory. The remaining chapters

investigate details of minor importance, and are especially interesting as showing his relation to Butler and Kant. The work is professedly a refutation of Francis Hutcheson, but is rather constructive than polemical. The theory he propounds is closely allied to that of Cudworth, but is interesting mainly in comparison with the subsequent theories of Kant. Right

and wrong belong to actions in themselves. By this he means, not that

the ethical value of actions is independent of their motive and end, but rather that it is unaffected by consequences, and

that it is more or less invariable for intelligent beings. II. This

ethical value is perceived by reason or understanding (which, unlike

Kant, he does not distinguish), which intuitively recognizes fitness or

congruity between actions, agents and total circumstances. Arguing that

ethical judgment is an act of discrimination, he endeavours to

invalidate the doctrine of the moral sense. Yet, in denying the

importance of the emotions in moral judgment, he is driven back to the

admission that right actions must be "grateful" to us; that, in fact,

moral approbation includes both an act of the understanding and an

emotion of the heart. Still it remains true that reason alone, in its

highest development, would be a sufficient guide. In this conclusion he

is in close agreement with Kant; reason is

the arbiter, and right is (1) not a matter of the emotions and (2) no

relative to imperfect human nature. Price's main point of difference

with Cudworth is

that while Cudworth regards the moral criterion as a vanua or

modification of the mind, existing in gere and developed by

circumstances, Price regards it as acquired from the contemplation of

actions, but acquired necessarily, immediately intuitively. In his view

of disinterested action he adds nothing to Butler. Happiness

he regards as the only end, conceivable by us, of divine Providence,

but it is a happiness wholly dependent upon rectitude. Virtue tends

always to happiness, and in the end must produce it in its perfect form. Price was a friend of the mathematician and clergyman Thomas Bayes. He edited Bayes' most famous work "Essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances" which contains Bayes' Theorem, one of the most fundamental theorems of probability theory. Price wrote an introduction to Bayes' paper which provides some of the philosophical basis of Bayesian statistics. Besides the above mentioned, Price wrote an Essay on the Population of England (2nd ed., 1780) which directly influenced Thomas Robert Malthus; two Fast - day Sermons, published respectively in 1779 and 1781 ; and Observations on the importance of the American Revolution and the means of rendering it a benefit to the World (1784). A complete list of his works is given as an appendix to Dr Priestley's Funeral Sermon. His views on the French Revolution are denounced by Burke in his Reflections on the Revolution in France. Notices of Price's ethical system occur in James Mackintosh's Progress of Ethical Philosophy, Jouffroy's Introduction to Ethics, William Whewell's History of Moral Philosophy in England; Alexander Bain's Mental and Moral Sciences.

Even when, in 1770, Price became morning preacher at the Gravel Pit Chapel in Hackney, he continued his afternoon sermons at NGUC. He also accepted duties at the meeting house in Old Jewry Street in the City of London.