<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Johannes Clauberg, 1622

- Painter Franz Stuck, 1863

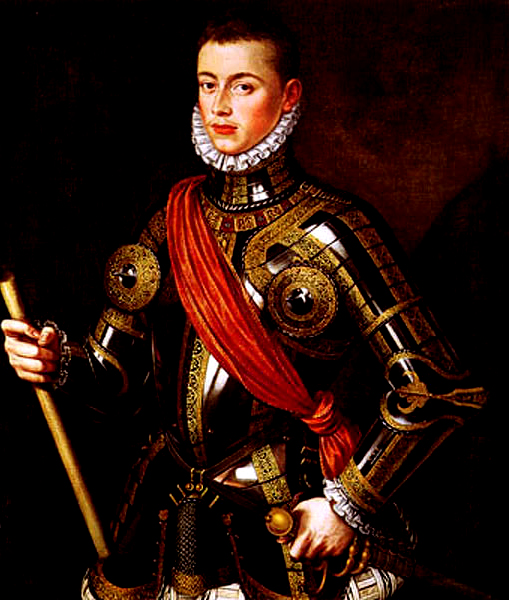

- Naval Commander John of Austria, 1547

PAGE SPONSOR

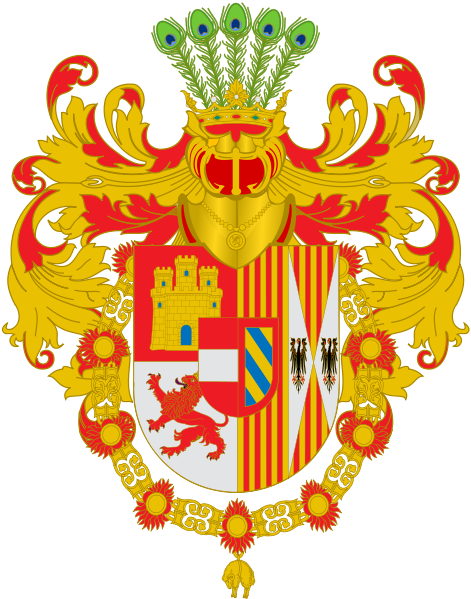

John of Austria (24 February, 1547 - 1 October 1578), in English traditionally known as Don John of Austria, in Spanish as Don Juan de Austria and in German as Ritter Johann von Österreich, was an illegitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. He became a military leader in the service of his half - brother, Philip of Spain and is best known for his naval victory at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 against the Ottoman Empire.

Born in Regensburg, Bavaria, he was the progeny of a liaison between Emperor Charles V and Barbara Blomberg, a burgher's daughter and singer. Barbara was promptly married to Hieronymus Kegel, a court functionary in Brussels, and her child became known as Jeromín. Before he turned the age of three, Jeromín was taken from his mother and put in the care of an old friend of Charles, Adrien de Bois who, in counsel with his wife Magdalen de Ulloa, placed the child as theirs, under a Flemish court musician, Franz Massy and his Spanish wife, Ana de Medina. Given money for their travel and his keep, they took him to Spain and settled in 1550 at Leganés, her village just outside Madrid. There, Jeromín learned Spanish and played with village boys, starting basic school with the priest at nearby Getafe. When he turned seven, by order of the Emperor, a courtier took him from his now widowed foster mother to the castle of Charles’ majordomo, Don Luis de Quijada, which was in Villagarcía de Campos, not far from Valladolid. Quijada’s strong willed wife, Doña Magdalena, took charge of Jeromín, grooming him in her household where he was given a solid curriculum of studies including Latin and French.

When Charles abdicated his Spanish crowns in 1556, he retired from Brussels to the remote monastery of Yuste in Spain. There he summoned Don Luis de Quijada to return as majordomo. In the summer of 1558, Quijada brought Magdalena and Jeromín to Yuste, where Charles, on several occasions before his death that September, saw his son, now a trim blond youth of eleven. Though he did not acknowledge him at the time, in a codicil to his will Charles had made provision for Jeromín, and expressed hope that he would enter the clergy and pursue an ecclesiastical career.

Charles' son and heir, Philip II of Spain, returned from Brussels in 1559, aware of his father’s will. Settled in Valladolid, he summoned Quijada to bring Jeromín to a hunt. When Philip appeared, Quijada told Jeromín to dismount and make proper obeisance to his king. When Jeromín did so, Philip asked him if he knew the identity of his father. When the boy did not know, Philip embraced him and explained that they had the same father and thus were brothers. He would ever after address him as "mi muy querido y amado hermano" (my very dear and beloved brother). Philip renamed him Juan (John), after a brother who died in infancy.

While they were dear as brothers, Philip was strict regarding protocol and did not accord John royal status. He was not considered an Infante (Spanish royal prince), nor was he to be addressed as "highness", a form reserved for royals and sovereign princes. In formal style he was "your excellency", the address used for a Spanish grandee, and known as Señor Don Juan de Austria. Don John did not live in a royal palace, but maintained a separate household with Luis and Magdalena Quijada now heading his service. Philip did allow Don John the incomes allocated to him by Charles so that he might maintain the status proper to the son of an emperor and brother of a king. In public ceremonies, Don John stood, walked or rode behind the royal family, but ahead of the grandees.

Yet, in many ways Don John was an intimate part of the royal family. Philip’s new queen, Elisabeth de Valois, was only a year older than Juan, and his ill fated son by his first marriage, Don Carlos, only two years older. Often in the company of the lively young set was Don John’s half - sister Joan, Princess of Portugal, a dozen years his senior. At the baptisms of his nieces, Elisabeth’s daughters Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catherine Michelle, it was the agile Don John who carried the infants to the baptismal font.

Philip, hoping that Don John would take up an ecclesiastical career, sent him to the University of Alcalá de Henares in the company of Don Carlos and Alessandro Farnese, Prince of Parma and son of Charles V’s other acknowledged illegitimate child, Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Parma (1522 – 86). At Alcalá in 1562 Don Carlos suffered a fractured skull that had a deleterious effect on his personality. In 1565, Farnese left to be married in Brussels, where his mother was Regent of the Low Countries. From Farnese Don John learned womanizing and, in time, acknowledged two illegitimate daughters, one in Spain, the other in Naples. The former, Ana de Austria (1568 – 1610), daughter of Ana de Mendoza y Lacerda, 1st Princess of Melito and 1st Duchess of Francavilla, became an abbess; the latter, Juana de Austria (11 September 1573 – 7 February 1630), after years in a convent, married an Italian nobleman, Francesco Branciforte, Prince of Pietraperzia (c. 1575 - 1622) in 1603. They had a daughter Margherita Branciforte, Princess of Butera (d. Rome, 24 January 1659), who married Federico Colonna (1601 - 25 September 1641) and had one son Antonio Colonna, Prince of Pietrapersia (1619 – 1623).

Don

John did not fulfill his father's and brother's hopes of joining the

clergy, for a military career was more to his liking. In 1565, the

18 year old left for Barcelona to join the armada for the relief of Malta which was being besieged by the Ottoman Turks. In 1566, he was awarded the 245th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. In 1568, when Don John turned 21, Philip appointed him Captain General of the Sea and commander of Spain’s Mediterranean galley fleet. Don John embarked with the fleet that spring, under the guidance of Philip’s confidant, Don Luis de Requeséns, Grand Commander of Castile and assisted by veterans such as Don Álvaro de Bazán. He patrolled Spain's coast and chased Barbary corsairs, his first foray into combat. Before

Don Juan's embarkment, the matter of Don Carlos had come to a head. The

prince's behaviour was such that Philip was almost alone in believing

he might yet be worthy of the throne. The prince’s confessor confided

that the prince admitted a desire to kill his father, which alarmed the

king. Don Carlos thought to flee court, with the idea that he might

bring peace to the Low Countries where rebellion against Philip’s rule

brewed. He sought the aid of Don Juan, who informed Philip: Don Carlos

was subsequently put under arrest. During

the summer of 1568, Don Juan was distressed to learn of Don Carlos'

death and devastated when, on coming ashore at the end of the

campaigning season, he learned of the death of the Queen. While he

joined Philip at prayer by the Queen's bier, he seems to have had a

falling out with the King over his place in the funeral. Later, he

withdrew to a monastery near Valladolid to spend time in prayer and

meditation. When news reached him at Christmastide of the revolt in Granada of the Moriscos (Moors who had been forced to convert to Christianity), he volunteered to serve in any capacity. The local grandees in charge, the Marquis of Mondéjar in Granada and the Marquis of los Vélez in Murcia,

soon fell out over matters of tactics, strategy and the place of

clemency. The revolt spread and aid came from Barbary and the Turks. In

April 1569 Philip appointed Don Juan commander - in - chief with Quijada as

his chief adviser. In Granada Don John built his forces with care,

learning about logistics and drill. Requeséns and Santa Cruz

patrolled the coast with their galleys, limiting aid and reinforcements

from Barbary. In December Don John unexpectedly took the field with a

large and well supplied army. First clearing rebels from near Granada, he then marched east through Guadix,

where veteran troops from Italy joined him, bringing his numbers to

12,000. In late January he assaulted the rebel stronghold of Galera.

Fighting was long and hard and casualties heavy. When Galera fell, Don

Juan had it levelled and salt ploughed into its soil. The surviving

inhabitants were sold into slavery. As

the campaign continued, a musket ball grazed Don John's helmet in a

skirmish, while Quijada was fatally wounded at his side. Philip

sympathized with Don John's distress at the loss of Quijada, who had

been like a father to him, but admonished him that generals should not

be in the thick of combat, but take a safe position from which to

direct the battle. His troops, however, came to see Don John as more

akin to his father Charles V than his famously desk bound brother

Philip. Increasingly, they addressed Don Juan as Your Highness. The

example of Galera and Don John's determined advance intimidated other

Morisco villages, which soon began to surrender to Don John’s superior

forces. Through 1570 the revolt gradually sputtered out as its leaders

quarreled, sought individual advantage, and murdered each other, while

the Turks and their Barbary allies turned to the invasion of the

Venetian colony of Cyprus. To eliminate the possibility of further revolts in Granada, Philip dispersed its Morisco population in small groups among the Old Christian towns

and villages of the Castilian hinterland, and hoped for their

assimilation into Spanish society as well as true observance of

Christianity. Eventually, Philip III would order the expulsion of all Moriscos from Spain in 1609. The War of Cyprus became the focus of Spain’s attention after Pope Pius V sent an envoy to urge Philip to join with him and Venice in a Holy League against

the Turks. Philip agreed and negotiations opened in Rome. Among

Philip's terms was the appointment of Don John as commander - in - chief of

the Holy League armada. While he agreed that Cyprus should be relieved,

he was also concerned to recover control of Tunis, where Turks had overthrown the regime of Philip's client Muslim ruler. Tunis posed an immediate threat to Sicily, one of Philip’s kingdoms. Philip also had in mind the eventual conquest of Algiers, whose corsairs posed a constant nuisance to Spain. Charles V had tried, and failed, to take it in 1541. While

Don John finished the pacification of Granada, negotiations dragged on

in Rome. In the summer of 1570 an allied fleet of Venetian galleys

belonging to the Venetians, Philip sailed for Cyprus, under the pope's

admiral Marcantonio Colonna. In charge of Philip’s contingent was the Genoese Gian Andrea Doria, a great - nephew of the renowned Andrea Doria.

On reaching the Turkish coast in September, Colonna and the Venetians

wished to press on to Cyprus while Doria argued that the season had

grown too late. Then news arrived that Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, had fallen, and only the port of Famagusta held

out. Sickness hit the Venetian fleet and a consensus grew that it was

best to return to port. The weather turned ugly and while Doria reached

port in good order, the Venetians were storm battered. Among the

Christian allies, animosities became open while the Turks tightened

their siege of Famagusta. The

Venetians repaired their galley fleet and readied six heavily armed

galleasses. The Pope hired twelve galleys from the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The dukes of Savoy and Parma also

provided galleys, and Alexander Farnese sailed in one. When the League

was formally signed in May, Don John was designated commander - in -

chief,

though it was late July before he sailed with the Spanish squadron from

Barcelona, and mid September before the entire Holy League armada got

underway from Messina.

Again some, like Doria, complained that the season grew late and

Famagusta had likely fallen. But Don John proved determined to fight,

and by his personal charisma rallied the allies, quelled their mutual

suspicions and inspired enthusiasm in what he called a holy cause. Don John found the Turkish fleet at Lepanto in the Gulf of Corinth.

After some debate, the Turks chose to fight, even though they had been

at sea all summer and disbanded some of their people. They had the

larger fleet, nearly 300 to Don John's 207 galleys and six galleasses. On 7 October 1571, the Turkish fleet emerged into the Gulf of Patras and

took battle formation. Bringing his fleet through islets known as the

Curzolaris (now mostly lost to the silting of the shoreline), Don John

deployed his armada into a left wing under Venetian command, a right

wing under Doria, a powerful center or main battle under himself, and a

strong rear guard under the Marquis of Santa Cruz. In all four

formations were galleys from each of the participating states. Two

galleasses each were assigned to the wings and center. Around

noon the battle commenced. The cannonade of the galleasses disrupted

the Turkish formations as they pressed to the attack, and the bigger

and more numerous guns of the Christian allies did devastating damage

as the Turkish right and center closed to board. In the seesaw fighting

on decks, the allies prevailed. Among their wounded was Miguel de Cervantes, who would later in Don Quixote describe combat aboard galleys and call Lepanto the greatest occasion known to the centuries, past, present and future. The Turkish left under Uluj Ali, governor general of

Algiers and their best admiral, tried to out-maneuver Doria’s wing,

drawing it away from the League center. When a gap appeared between

Doria and the center, Uluj Ali made a quick turn about and aimed at the

gap, smashing three galleys of the Knights of Malta on

Don John’s right flank. Don John came around smartly while the Marquis

of Santa Cruz hit Uluj Ali hard with his rear guard. Uluj Ali himself

and maybe half his wing escaped. The victory was near total, with the

Turkish fleet virtually annihilated and thousands of veterans lost. The

League’s losses were hardly negligible, with over 7000 dead. In the

evening a storm broke and the victors had to head for port, while

sporadic Greek uprisings were ruthlessly suppressed by the Turks. All looked forward to the campaign of 1572, but events in France, with the growth of Protestant Huguenot power, seemed to threaten Philip's Low Countries, where the Duke of Alba had restored an uneasy order. Philip ordered Don Juan to hold his part of the Holy League armada at Palermo,

prepared to respond to events in France. Colonna took the rest into

Greek waters, but achieved nothing. By the time Don Juan joined his

allies in late summer, and attempted to take the Turkish citadel of Modon on the Peloponnesus (then known as the Morea), the Turks had too many reinforcements in place. Don John wintered in Naples, from which he made his first visit to his half - sister Margaret, Duchess of Parma, in l’Aquila.

They had corresponded for some time and would continue to do so. He

confided in her about his love affairs, and after the birth of an

illegitimate daughter had her delivered to Margaret’s care. His

relations with the new Viceroy of Naples, Cardinal Granvelle,

an old and experienced diplomat, were not easy, but he did learn more

of statecraft and the problems of northern Europe. At some point he

began to entertain fantasies of liberating Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, held captive by Queen Elizabeth I, and perhaps marrying her and taking England's throne. Such an idea received encouragement in Rome. Yet he dreaded the

idea of the post he would need to achieve it, that of Governor General

of the rebellious Low Countries. In

May 1572 Pope Pius V had died, and in early 1573, the Venetians,

distrusting Philip II, made a separate peace with the Turks. Don John

put his energy into the recovery of Tunis, which he achieved that fall,

restoring a client Muslim ruler. Against advice from Madrid to raze

Tunis and destroy its harbor and the great fortress of La Goletta,

erected by Charles V after his conquest of Tunis in 1535, Don John

chose to keep La Goletta, which had held out in 1570, and build a new

fortress inside Tunis to dominate the city. He and the Marquis of Santa

Cruz planned next to take Algiers, while critics, including Granvelle,

hinted that Don John dreamed of becoming King of Tunis. But

by 1573 the revolt of the Low Countries had revived and Don John found

himself increasingly short on funds. While his name had been bruited

for the post of Governor General to succeed the Duke of Alba, it was

the older Requeséns who received it. In 1574 unrest spread in Genoa against

Doria and his dominant party. Genoa was Spain’s chief banker, and Don

John found himself preoccupied by Genoese politics. That summer a huge

Turkish armada under Uluj Ali struck Tunis and within weeks, both La

Goletta and the new city citadel were lost. Don John had hurried to

Palermo and assembled all available forces, but it was too little and

too late. He

came to feel abandoned and though Philip had enhanced his authority

over the viceroys of Naples and Sicily, who had not always proved

cooperative, he returned to Madrid at the beginning of 1575 to confer

in person with Philip and the Council of War. He claimed to be unaware

that orders had been sent that he remain in Italy. On his return there,

he once again became entangled in Genoese politics, which had become

more turbulent after Philip declared bankruptcy. Wars on two fronts,

the Low Countries and the Mediterranean, had overtaxed his finances,

and he suspended payments on debts prior to their renegotiation. With

Santa Cruz in Naples, Don John could undertake little but occasional

punitive strikes against Tunisian corsair lairs with his reduced fleet. Don

John and Santa Cruz had planned a larger campaign for 1576, when in May

he received the long dreaded orders to proceed directly to the Low

Countries as Governor General, following the death of Requeséns.

In Rome he once more received encouragement in his schemes to liberate

the Queen of Scots, making the governor generalship more attractive. In

northern Italy he halted, and sent his secretary Juan de Escobedo to

Spain, to secure more money and win Philip’s consent for his plans for

the Queen of Scots. When by late summer Escobedo had not returned, Don

John sailed for Spain. His shocked brother met with him privately at the Escorial.

Philip seems to have accepted Don Juan’s plans for the Queen of Scots,

but only after he had secured peace in the Low Countries. Because he

was short of money, Philip expected Don John to achieve peace through

diplomacy and negotiation. Having received his instructions, Don Juan

and a few companions made a dash for the Low Countries across France,

rent by religious civil war. Fearing Protestant assassins, Don John

wore the disguise of a Moorish slave. While grievances in the Low Countries were many, at the heart of the revolt was religion, militant Calvinism on

the rebel side, Roman Catholicism on Philip’s. Don John was a convinced

Catholic, had crusaded for the Cross against the Muslim Turks and

regarded Protestants simply as heretics. But some, particularly in the

Low Countries, argued that limited toleration might be the only

feasible solution for the revolt. Of the historic seventeen provinces, Holland and Zeeland were largely in rebel control, and others were threatened. The rebels had made William, Prince of Orange, their leader. In the meantime, after Requeséns’s death Philip’s Army of Flanders, its pay in arrears, mutinied and began to maraud for loot and stores in the provinces not under rebel control. The States General of the Low Countries assembled at Ghent while

local authorities raised troops for self defense. Delegates from the

rebel provinces met with their fellows to find grounds for a common

cause. In early November, mutineers sacked the city of Antwerp in what came to be called "the Spanish Fury."

At Ghent the delegates signed a Pacification that granted limited

tolerance and authorized the raising of an army to deal with Philip’s

mutinous troops, whom they demanded be removed. Don John got the news of the sack in Luxembourg soon after his arrival, and learned that his acceptance as Governor General depended upon his acceding to the Pacification of Ghent.

Don Juan negotiated from Luxembourg, separate and loyal. He knew that

removing the army would deprive him of the means to invade England and

liberate the Queen of Scots, so he suggested that if the troops must

go, it would be best to send them by sea and asked the States General

to provide shipping. The States General, urged by a suspicious Queen

Elizabeth who knew Don John's ambitions, demurred and insisted they

depart overland. They eventually did, marching south loaded with their

plunder. With the army departing, the matter of toleration became the

chief sticking point, with rebel demands that the Calvinist faith be

practiced openly in the rebel provinces and be tolerated in the others,

according to local initiative. These were terms neither Philip nor he

would accept, but as Don Juan had no means of using force, he could

only temporize. He issued a Perpetual Edict accepting

the Pacification, but, confident that Catholics still remained the

majority in the Low Countries, stipulated that panels of theologians

hammer out the matter of toleration, with all to abide by their

decisions. As most were tired of wrangling and bloodshed, the States

General accepted Don John as Governor General, and in May 1577 he made

his Joyous Entry into

Brussels, promising to respect its historic privileges, which by

extension had become the privileges of the seventeen provinces. As

he assumed his office, he had to deal with the problem of his mother.

Widowed, Barbara Blomberg in Ghent scandalized her neighbors by her

conduct. She had had two sons by Kegel, of whom one drowned and the

other served in the royal army. At times she disowned Don John, despite

receiving a government pension on his behalf. He eventually persuaded

her to journey to Italy and meet Margaret of Parma. Her ship took her

instead to Spain, where she was eventually settled on Escobedo’s

property near Santander and lived till 1598. For

the sake of peace, Don John agreed to meet with the rebel leader, the

Prince of Orange, hoping to win him over with his famous charm. The

meeting never took place. Reports came from reliable sources that

fanatical Protestants aimed to assassinate him. He took them seriously

and in July used the visit of Marguerite de Valois, Queen of Navarre, to Spain as an excuse to meet her near Namur.

There were stories that on his dash through France they had a secret

tryst in Paris. After she resumed her journey, Don John and his

selected companions seized the citadel of Namur in violation of the Perpetual Edict.

He sent Escobedo to Spain to explain to Philip the impossibility of

gaining an acceptable peace with heretics and calling for the return of

the army. The States General declared war on Don John. Philip,

his finances only slightly improved, was distressed. Did he believe Don

John could have succeeded in negotiations without accepting religious

toleration, or at least through them buy more time. For reasons that

have never become clear, Philip’s chief secretary, Antonio Pérez,

insinuated that Escobedo was behind Don John's call for the army and

had fed Don Juan’s ambitions to liberate the Queen of Scots, maybe

more. Whatever his doubts about his brother’s intentions, Philip sent

the army back under Alexander Farnese, but in March 1578 either

approved or acquiesced in Escobedo’s murder by Pérez’s hirelings. Don John, Farnese and the army had routed the States General's army at Gembloux that

January. On the news of Escobedo’s murder Don Juan was perplexed, and

knew not whom to believe. Tired and increasingly ill, he campaigned

through the summer with mixed success, but failed in his attempt to

take Brussels, after receiving a setback in the Battle of Rijmenam on 2

August 1578. He did win more and more of the Catholic nobles and towns

to the royal cause. As ever money was a problem, and he felt his life

was being doled out in bits and pieces, and complained to friends of

the endless rainy weather. In September he pulled the army into camp

near Namur to regroup, as his health failed. On 1 October 1578, he died

of what contemporaries called camp fever, typhus.

His army gave him a funeral due a hero. He had appointed Farnese his

successor as Governor General, an appointment Philip confirmed. His body was dissected, returned

to Spain, reassembled and placed by Philip to rest in the unfinished

crypt of the Escorial, not far from their father. In time the body had

its own niche and a fine nineteenth century marble effigy. Philip,

reviewing Don John's papers, found no evidence of disloyalty and put

Pérez under arrest. Dead

at thirty-one, Don John of Austria was regarded by his contemporaries

as one of the great captains of his age, as well as a romantic figure.

His life inspired the 1835 play Don Juan d'Autriche by Casimir Delavigne, which served in turn as a source for two operas, Don John of Austria by Isaac Nathan in 1847 and Don Giovanni d'Austria by Filippo Marchetti in 1879. Lepanto remains his great triumph. G.K. Chesterton in 1911 published a poem titled "Lepanto", and dubs Don Juan "the last knight of Europe." Louis de Wohl published

the novel "The Last Crusader: A Novel about Don Juan of Austria" in

1956. Don Juan’s ambitions, above all for the Queen of Scots, tend to

obscure his talent for statecraft and ability to lead. Frustrated by

the religious factiousness in the Low Countries, he began the policies

that Farnese would follow in keeping the ten southern provinces, today’s Belgium, Luxembourg and most of the French Netherlands, Roman Catholic and loyal to Philip, and limiting the revolt to the northern seven that eventually became the Dutch Republic.