<Back to Index>

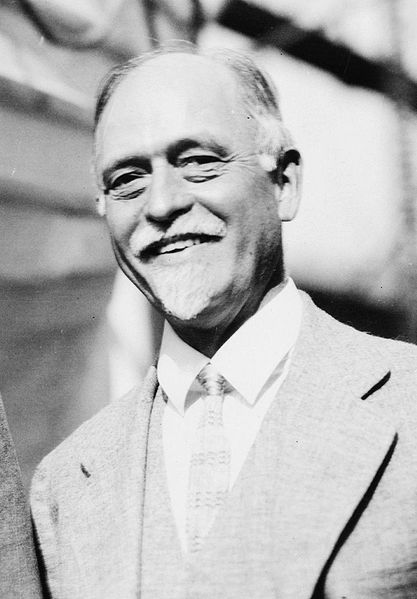

- Economist Irving Fisher, 1867

- Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1807

- Member of Parliament William George Frederick Cavendish - Scott - Bentinck, 1802

PAGE SPONSOR

Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867 – April 29, 1947) was an American economist, health campaigner, and eugenicist, and one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though he later rejected the underlying theory of general equilibrium, and his later work on debt deflation is instead considered in the Post - Keynesian school. Although he was perhaps the first celebrity economist, his reputation during his lifetime was irreparably harmed by his sanguine attitude immediately prior to the crash of 1929, and his theory of debt deflation was ignored in favor of the work of John Maynard Keynes. His reputation has since recovered in neoclassical economics since his work was popularized in the late 1950s (Hirshleifer 1958), and more widely due to an increased interest in debt deflation in the Late 2000s recession.

Fisher's work on the quantity theory of money was one of the major influences on the development of Milton Friedman's "monetarism." Friedman called Fisher "the greatest economist the United States has ever produced." Other concepts named after Fisher include the Fisher equation, the Fisher hypothesis, the international Fisher effect, and the Fisher separation theorem.

Fisher was born in Saugerties, New York.

His father was a teacher and Congregational minister, who raised his

son to believe he must be a useful member of society. As a child, he

had remarkable mathematical ability and a flair for invention. A week

after he was admitted to Yale College,

his father died at age 53. Irving carried on, however, supporting his

mother, brother, and himself, mainly by tutoring. He graduated with a

B.A degree in 1888; he was a member of Skull and Bones. Fisher's

best subject was mathematics, but economics better matched his social

concerns. He went on to write a doctoral thesis combining both

subjects, on mathematical economics. Irving was granted the first Yale Ph.D. in economics, in 1891. His advisers were the physicist Willard Gibbs and the economist William Graham Sumner.

Fisher did not realize at the outset that there was already a

substantial European literature on mathematical economics.

Nevertheless, his thesis made a contribution European masters such as Francis Edgeworth recognized

as first rate. He constructed a wonderful machine of pumps and levers

to complement and illustrate his thesis. While his books and articles

on economic topics exhibited unusual (for the time) mathematical

sophistication, Fisher always wished to bring his analysis to life and

to present his theories in a very lucid manner. From 1890 onward he was

at Yale as a tutor, then becoming

professor of political economy in 1898, and professor emeritus in 1935. He edited the Yale Review from 1896 to 1910 and was active in many learned societies, institutes, and welfare organizations. He was a leading proponent of econometrics in

its historical development. Among his special interests were

temperance, eugenics, public health, and world peace. He won a New York

Medical Society prize for the invention of a tent for the treatment of

tuberculosis victims. He strongly supported prohibition in the 1920s. Tobin

(1985) argues the intellectual breakthroughs that mark the neoclassical

revolution in economic analysis occurred in Europe around 1870. The

next two decades witnessed lively debates in which the new theory more

or less absorbed or was absorbed in the classical tradition that

preceded and provoked it. In the 1890s, according to Joseph A. Schumpeter there emerged Fisher's research into basic theory did not touch the great social issues of the day. Monetary economics did and this became the main focus of Fisher’s work. Fisher’s Appreciation and interest was

an abstract analysis of the behavior of interest rates when the price

level is changing. It emphasized the distinction between real and

monetary rates of interest which is fundamental to the modern analysis

of inflation. However Fisher believed that investors and savers —

people

in general — were afflicted in varying degrees by “money illusion”;

they could not see past the money to the goods the money could buy. In

an ideal world, changes in the price level would have no effect on

production or employment. In the actual world with money illusion,

inflation (and deflation) did serious harm.

Fisher

was a prolific writer, producing journalism, as well as technical books

and articles, addressing the problems of the First World War, the

prosperous 1920s and the depressed 1930s. He died in New York City in

1947, at the age of 80. Fisher's theory of the price level was the following variant of the quantity theory of money. Let M = stock of money, P = price level, T = amount of transactions carried out using money, and V = the velocity of circulation of money. Fisher then proposed that these variables are interrelated by the Equation of exchange: Later economists replaced the amorphous T with y or "Q", real output, nearly always measured by real GDP. Fisher was also the first economist to distinguish clearly between real and nominal interest rates: where r is

the real interest rate, i is the nominal interest rate, and inflation

is a measure of the increase in the price level. When inflation is

sufficiently low, the real interest rate can be approximated as the

nominal interest rate minus the expected inflation rate. The resulting equation is known as the Fisher equation in his honor. For

more than forty years, Fisher elaborated his vision of the damaging

“dance of the dollar” and devised schemes to “stabilize” money, i.e., to

stabilize the price level. He was one of the first to subject macroeconomic data,

including the money stock, interest rates, and the price level, to

statistical analysis. In the 1920s, he introduced the technique later

called distributed lags. In 1973, the Journal of Political Economy reprinted his 1926 paper on the statistical relation between unemployment and inflation, retitling it as "I discovered the Phillips curve". Index numbers played an important role in his monetary theory, and his book The Making of Index Numbers has remained influential down to the present day. While

most of Fisher's energy went into social causes and business ventures,

and the better part of his scientific effort was devoted to monetary

economics, he is best remembered today in neoclassical economics for

his theory of interest and capital, studies of an ideal world from

which the real world deviated at its peril. His most enduring

intellectual work has been his theory of capital, investment, and interest rates, first exposited in his The Nature of Capital and Income (1906) and elaborated on in The Rate of Interest (1907). His 1930 treatise, The Theory of Interest, summed up a lifetime's work on capital, capital budgeting, credit markets, and the determinants of interest rates, including the rate of inflation. Fisher

saw that subjective economic value is not only a function of the amount

of goods and services owned or exchanged but also of the moment in time

when they are purchased. A good available now has a different value

than the same good available at a later date; value has a time as well

as a quantity dimension. The relative price of goods available at a future date, in terms of goods sacrificed now, is measured by the interest rate.

Fisher made free use of the standard diagrams used to teach

undergraduate economics, but labelled the axes "consumption now" and

"consumption next period" instead of, e.g., "apples" and "oranges." The

resulting theory, one of considerable power and insight, was exposited

in considerable detail in The Theory of Interest. This theory, since generalized to the case of K goods and N periods (including the case of infinitely many periods) using the notion of a vector space,

has become the canonical theory of capital and interest in contemporary

economics. The nature

and scope of this theoretical advance was not fully appreciated,

however, until Hirshleifer's (1958) re-exposition, so that Fisher did

not live to see this theory's ultimate triumph. Following the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, Fisher developed a theory of economic crises called debt - deflation, which rejected general equilibrium theory and attributed crises to the bursting of a credit bubble. According to the debt deflation theory, a sequence of effects of the debt bubble bursting occurs: This theory was ignored in favor of Keynesian economics, partly due to the damage to Fisher's reputation from his sanguine attitude prior to the crash, but has experienced a revival of mainstream interest since the 1980s, particularly since the Late 2000s recession, and is now a main theory with which he is popularly associated.

The stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression cost Fisher much of his personal wealth and academic reputation. He famously predicted, a few days before the crash, "Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau." Irving

Fisher stated on October 21 that the market was "only shaking out of

the lunatic fringe" and went on to explain why he felt the prices still

had not caught up with their real value and should go much higher. On

Wednesday, October 23, he announced in a banker’s meeting “security

values in most instances were not inflated.” For months after the

Crash, he continued to assure investors that a recovery was just around

the corner. Once the Great Depression was in full force, he did warn that the ongoing drastic deflation was

the cause of the disastrous cascading insolvencies then plaguing the

American economy because deflation increased the real value of debts

fixed in dollar terms. Fisher was so discredited by his 1929

pronouncements and by the failure of a firm he had started that few

people took notice of his "debt - deflation" analysis of the Depression.

People instead eagerly turned to the ideas of Keynes. Fisher's debt - deflation scenario has made something of a comeback since 1980 or so. The lay public perhaps knew Fisher best as a health campaigner and eugenicist. In 1898 he found that he had tuberculosis,

the disease that killed his father. After three years in sanatoria,

Fisher returned to work with even greater energy and with a second

vocation as a health campaigner. He advocated vegetarianism, avoiding red meat, and exercise, writing How to Live: Rules for Healthful Living Based on Modern Science, a USA best seller. In 1912 he also became a member of the scientific advisory to the Eugenics Record Office and served as the secretary of the American Eugenics Society. Fisher was also a strong believer in the now ridiculed "focal sepsis" theory of physician Henry Cotton, who believed that mental illness was

attributable to infectious material residing in the roots of the teeth,

recesses in the bowels, and other places in the human body, and that

surgical removal of this infectious material would cure the patient's

mental disorder. Fisher believed in these theories so thoroughly that

when his daughter Margaret Fisher was diagnosed with schizophrenia, Fisher had numerous sections of her bowel and colon removed at Dr. Cotton's hospital, eventually resulting in his daughter's death. Fisher was also an ardent supporter of the Prohibition of alcohol in

the United States, and wrote three short books arguing that Prohibition

was justified on the grounds of both public health and hygiene, as well

as economic productivity and efficiency, and should therefore be

strictly enforced by the United States government.