<Back to Index>

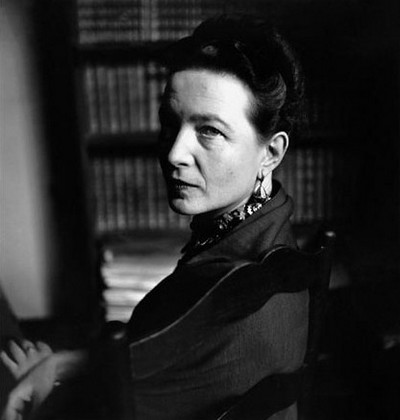

- Philosopher Simone Ernestine Lucie Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir, 1908

- Dramatist Thomas William Robertson, 1829

- Women's Rights Activist Carrie Chapman Catt, 1859

PAGE SPONSOR

Simone-Ernestine-Lucie-Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir, often shortened to Simone de Beauvoir (January 9, 1908 – April 14, 1986), was a French existentialist philosopher, public intellectual, and social theorist. She wrote novels, essays, biographies, an autobiography in several volumes, and monographs on philosophy, politics, and social issues. She is now best known for her metaphysical novels, including She Came to Stay and The Mandarins, and for her 1949 treatise The Second Sex, a detailed analysis of women's oppression and a foundational tract of contemporary feminism. She is also noted for her lifelong polyamorous relationship with Jean - Paul Sartre.

Simone de Beauvoir was born in Paris, the eldest daughter of Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir, a legal secretary who once aspired to be an actor, and Françoise (née) Brasseur, a banker’s daughter and devout Catholic, from a well off background. Her younger sister, Hélène, was born two years later. The family struggled to maintain their bourgeois status after losing much of their fortune shortly after World War I, and Françoise insisted that the two daughters be sent to a prestigious convent school. Beauvoir herself was deeply religious as a child — at one point intending to become a nun — until a crisis of faith at age 14. She remained an atheist for the rest of her life.

Beauvoir was intellectually precocious from a young age, fueled by her father’s encouragement: he reportedly would boast, “Simone thinks like a man!” After passing baccalaureate exams in mathematics and philosophy in 1925, she studied mathematics at the Institut Catholique and literature / languages at the Institut Sainte - Marie. She then studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, writing her thesis on Leibniz for Léon Brunschvicg. She first worked with Maurice Merleau - Ponty and Claude Lévi - Strauss when all three completed their practice teaching requirements at the same secondary school. Although not officially enrolled, she sat in on courses at the École Normale Supérieure in preparation for the agrégation in philosophy, a highly competitive postgraduate examination which serves as a national ranking of students. It was while studying for the agrégation that she met École Normale students Sartre, Paul Nizan, and René Maheu (who gave her the lasting nickname "Castor", or beaver). The jury for the agrégation narrowly awarded Sartre first place instead of Beauvoir, who placed second and, at age 21, was the youngest person ever to pass the exam.

Sartre was dazzlingly intelligent and was just under 5 feet (1.5 m) tall. He allowed Beauvoir to talk about herself. During October 1929, the two became a couple and Sartre asked her to marry him. One day while they were sitting on a bench outside the Louvre, he said, "Let's sign a two - year lease". Near the end of her life, Beauvoir said, "Marriage was impossible. I had no dowry." So they became an imaginary married couple. Beauvoir chose to never marry and did not set up a joint household with Sartre. She never had children. This

gave her time to earn an advanced academic degree, to join political

causes and to travel, write, teach, and to have (male and female - the

latter often shared) lovers.

A number of de Beauvoir's young female lovers were underage, and the nature of some of these relationships, some of which she instigated while working as a school teacher, has lead to a biographical controversy and debate over whether de Beauvoir had inclinations towards paedophilia. A former student, Bianca Lamblin, originally Bianca Bienenfeld, later wrote critically about her seduction by her teacher, Simone de Beauvoir, when she was a 17 year old lycee student in her book, Mémoires d'une jeune fille dérangée. In 1941, de Beauvoir was suspended from her teaching job, due to an accusation that she had, in 1939, seduced her 17 year old lycee pupil Nathalie Sorokine. De Beauvoir would, along with other French intellectuals, later petition for an abolition of all age of consent laws in France.

In 1943, Beauvoir published She Came to Stay, a fictionalized chronicle of her and Sartre's sexual relationship with her students, Olga Kosakiewicz and Wanda Kosakiewicz. Olga was one of her students in the Rouen secondary school where Beauvoir taught during the early 30s. She grew fond of Olga. Sartre tried to pursue Olga but she denied him; he began a relationship with her sister Wanda instead. Sartre supported Olga for years until she met and married her husband, Beauvoir's lover Jacques - Laurent Bost. At Sartre's death, he was still supporting Wanda. In the novel, set just before the outbreak of World War II, Beauvoir makes one character from the complex relationships of Olga and Wanda. The fictionalized versions of Beauvoir and Sartre have a ménage à trois with the young woman. The novel also delves into Beauvoir and Sartre's complex relationship and how it was affected by the ménage à trois.

Beauvoir's metaphysical novel She Came to Stay was followed by many others, including The Blood of Others which explores the nature of individual responsibility, and The Mandarins, which won her the Prix Goncourt, France's highest literary prize. The Mandarins is set just after the end of World War II. The Mandarins depicted Sartre, Nelson Algren, and many philosophers and friends among Sartre and Beauvoir's intimate circle.

In 1944 Beauvoir wrote Pyrrhus et Cinéas, a discussion of an existentialist ethics, which inspired her to write more on the subject. This book, Pour Une Morale de L'ambiguïté (The Ethics of Ambiguity, 1947) is perhaps the most accessible entry into French existentialism. Its simplicity keeps it understandable, in contrast to the abstruse character of Sartre's Being and Nothingness. The ambiguity about which Beauvoir writes clears up some inconsistencies that many, Sartre included, have found in major existentialist works such as Being and Nothingness.

At the end of World War II, Beauvoir and Sartre edited Les Temps Modernes, a political journal Sartre founded along with Maurice Merleau - Ponty and others. Beauvoir used Les Temps Modernes to promote her own work and explore her ideas on a small scale before fashioning essays and books. Beauvoir remained an editor until her death.

Chapters of Le deuxième sexe (The Second Sex) were originally published in Les Temps modernes. The second volume came a few months after the first in France. It was very quickly published in America as The Second Sex, due to the quick translation by Howard Parshley, as prompted by Blanche Knopf, wife of publisher Alfred A. Knopf.

Because Parshley had only a basic familiarity with the French language,

and a minimal understanding of philosophy (he was a professor of

biology at Smith College), much of Beauvoir's book was mistranslated or inappropriately cut, distorting her intended message. For

years Knopf prevented the introduction of a more accurate retranslation

of Beauvoir's work, declining all proposals despite the efforts of

existentialist scholars. Only in 2009 was there a second translation, to mark the 60th anniversary of

the original publication. Constance Borde and Sheila

Malovany - Chevallier produced the first integral translation,

reinstating a third of the original work. In her own way, Beauvoir anticipated the sexually charged feminism of Erica Jong and Germaine Greer. Algren was outraged by the frank way Beauvoir later described her American sexual experiences in The Mandarins (dedicated

to Algren, on whom the character Lewis Brogan was based) and in her

autobiographies. He vented his outrage when reviewing American

translations of her work. Much material bearing on this episode in

Beauvoir's life, including her love letters to Algren, entered the

public domain only after her death. In the chapter "Woman: Myth and Reality" of The Second Sex,

Beauvoir argued that men had made women the "Other" in society by

putting a false aura of "mystery" around them. She argued that men used

this as an excuse not to understand women or their problems and not to

help them, and that this stereotyping was always done in societies by

the group higher in the hierarchy to the group lower in the hierarchy.

She wrote that this also happened on the basis of other categories of

identity, such as race, class, and religion. But she said that it was

nowhere more true than with sex in which men stereotyped women and used

it as an excuse to organize society into a patriarchy. The Second Sex, published in French, sets out a feminist existentialism which prescribes a moral revolution. As an existentialist, Beauvoir believed that existence precedes essence; hence one is not born a woman, but becomes one. Her analysis focuses on the Hegelian concept of the Other.

It is the (social) construction of Woman as the quintessential Other

that Beauvoir identifies as fundamental to women's oppression. The

capitalized 'O' in "other" indicates the wholly other. Beauvoir argued that women have historically been considered deviant, abnormal. She said that even Mary Wollstonecraft considered men to be the ideal toward which women should aspire. Beauvoir said

that this attitude limited women's success by maintaining the

perception that they were a deviation from the normal, and were always

outsiders attempting to emulate "normality". She believed that for

feminism to move forward, this assumption must be set aside. Beauvoir asserted that women are as capable of choice as men, and thus can choose to elevate themselves, moving beyond the 'immanence' to which they were previously resigned and reaching 'transcendence', a position in which one takes responsibility for oneself and the world, where one chooses one's freedom. A critical essay, "Le Malentendu du Deuxième Sexe", was written by Suzanne Lilar in 1969. A new translation of The Second Sex for the first time gives access to the entire text in English, as Irene Gammel writes in a Globe and Mail review:

"The single most important advantage of this new translation is its

completeness, combined with the translators' courage to transpose

Beauvoir's existential language, thereby giving readers a sense of

Beauvoir's channelling of Hegel, Marx and others." Beauvoir wrote popular travel diaries about her travels in the United States and China,

and published essays and fiction rigorously, especially throughout the

1950s and 1960s. She published several volumes of short stories,

including The Woman Destroyed, which, like some of her other later work, deals with aging. In 1980 she published When Things of the Spirit Come First,

a set of short stories centered around and based upon women important

to her earlier years. The stories were written well before the novel She Came to Stay, but Beauvoir did not think they were worthy of publication until about forty years later. Sartre and Merleau - Ponty had a longstanding feud, which led Merleau - Ponty to leave Les Temps Modernes.

Beauvoir sided with Sartre and ceased to associate with Merleau - Ponty.

In Beauvoir's later years, she hosted the journal's editorial meetings

in her flat and contributed more than Sartre, whom she often had to

force to offer his opinions. Beauvoir also notably wrote a four-volume autobiography, consisting of: Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter; The Prime of Life; Force of Circumstance (sometimes published in two volumes in English translation: After the War and Hard Times); and All Said and Done. In the 1970s Beauvoir became active in France's women's liberation movement. She signed the Manifesto of the 343 in

1971, a list of famous women who claimed to have had an abortion, then

illegal in France. Some argue most of the women had not had abortions,

including Beauvoir, but given the secrecy surrounding the issue, this

cannot be known. Signatories were diverse as Catherine Deneuve, Delphine Seyrig, and Beauvoir's sister Poupette. In 1974, abortion was legalized in France. Her 1970 long essay La Vieillesse (The Coming of Age)

is a rare instance of an intellectual meditation on the decline and

solitude all humans experience if they do not die before about age 60.

In 1981 she wrote La Cérémonie Des Adieux (A Farewell to Sartre), a painful account of Sartre's last years. In the opening of Adieux,

Beauvoir notes that it is the only major published work of hers which

Sartre did not read before its publication. She and Sartre always read

one another's work. After

Sartre died, Beauvoir published his letters to her with edits to spare

the feelings of people in their circle who were still living. After

Beauvoir's death, Sartre's adopted daughter and literary heir Arlette

Elkaïm would not let many of Sartre's letters be published in

unedited form. Most of Sartre's letters available today have Beauvoir's

edits, which include a few omissions but mostly the use of pseudonyms.

Beauvoir's adopted daughter and literary heir Sylvie Le Bon, unlike Elkaïm, published Beauvoir's unedited letters to both Sartre and Algren. Beauvoir died of pneumonia in Paris, aged 78. She is buried next to Sartre at the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris. Since her death, her reputation has grown. Especially in academia, she is considered the mother of post 1968 feminism. There has also been a growing awareness of her as a major French thinker and existentialist philosopher. Contemporary

discussion analyzes the influences of Beauvoir and Sartre on one

another. She is seen as having influenced Sartre's masterpiece, Being and Nothingness, while also having written much on philosophy that is independent of Sartrean existentialism.

Some scholars have explored the influences of her earlier philosophical

essays and treatises upon Sartre's later thought. She is studied by

many respected academics both within and outside philosophy circles,

including Margaret A. Simons and Sally Scholtz. Beauvoir's life has

also inspired numerous biographies. In 2006, the city of Paris commissioned architect Dietmar Feichtinger to design a sophisticated footbridge across the Seine River. The bridge was named the Passerelle Simone - de - Beauvoir in her honor. It leads to the new Bibliothèque nationale de France.