<Back to Index>

- Physicist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, 1742

- Bluesman William James "Willie" Dixon, 1915

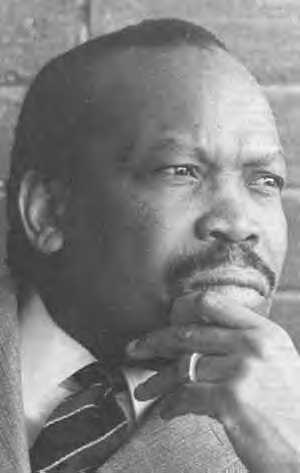

- 1st President of Botswana Seretse Khama, 1921

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Seretse Khama, KBE (1 July 1921 – 13 July 1980) was a statesman from Botswana. Born into one of the more powerful of the royal families of what was then the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, and educated abroad in neighbouring South Africa and in the United Kingdom, he returned home — with a popular but controversial bride -- to lead his country's independence movement. He founded the Botswana Democratic Party in 1962 and became Prime Minister in 1965. In 1966, Botswana gained independence and Khama became its first president. During his presidency, the country underwent rapid economic and social progress.

Seretse Khama was born in 1921 in Serowe, in what was then the Bechuanaland Protectorate. He was the son of Sekgoma Khama II, the paramount chief of the Bamangwato people, and the grandson of Khama III, their king. The name "Seretse" means “the clay that binds together,” and was given to him to celebrate the recent reconciliation of his father and grandfather; this reconciliation assured Seretse’s own ascension to the throne with his aged father’s death in 1925. At the age of four, Seretse became kgosi (king), with his uncle Tshekedi Khama as his regent and guardian.

After spending most of his youth in South African boarding schools, Khama attended Fort Hare University College there, graduating with a general B.A. in 1944. He then travelled to the United Kingdom and spent a year at Balliol College, Oxford, before joining the Inner Temple in London in 1946, to study to become a barrister. In June 1947, Khama met Ruth Williams, an English clerk at Lloyd's of London, and after a year of courtship, married her. The interracial marriage sparked a furore among both the apartheid government

of South Africa and the tribal elders of the Bamangwato. On being

informed of the marriage, Khama's uncle Tshekedi Khama demanded his

return to Bechuanaland and the annulment of the marriage. Khama did

return to Serowe but after a series of kgotlas (public meetings), was re-affirmed by the elders in his role as the kgosi in

1949. Ruth Williams Khama, travelling with her new husband, proved

similarly popular. Admitting defeat, Tshekedi Khama left Bechuanaland,

while Khama returned to London to complete his studies. However,

the international ramifications of his marriage would not be so easily

resolved. Having banned interracial marriage under the apartheid

system, South Africa could not afford to have an interracial couple

ruling just across their northern border. As Bechuanaland was then a

British protectorate (not a colony), the South African government immediately exerted pressure to have Khama removed from his chieftainship. Britain’s Labour government, then heavily in debt from World War II,

could not afford to lose cheap South African gold and uranium supplies.

There was also a fear that South Africa might take more direct action

against Bechuanaland, through economic sanctions or a military

incursion. The British government therefore launched a parliamentary enquiry into Khama’s fitness for the chieftainship. Though the investigation

reported that he was in fact eminently fit to rule Bechuanaland, "but

for his unfortunate marriage", the

government ordered the report suppressed (it would remain so for thirty

years), and exiled Khama and his wife from Bechuanaland in 1951. The

sentence would not last nearly so long. Various groups protested

against the government decision, holding it up as evidence of British

racism. In Britain itself there was wide anger at the decision and

calls for the resignation of Lord Salisbury, the minister responsible. A deputation of

six Bamangwato travelled to London to see the exiled Khama and Lord

Salisbury, in an echo of the 1895 deputation of three Bamangwato kgosis to Queen Victoria, but with no success. However, when ordered by the British High Commission to replace Khama, the people refused to do so. In

1956, Seretse and Ruth Khama were allowed to return to Bechuanaland as

private citizens, after he had renounced the tribal throne. Khama began

an unsuccessful stint as a cattle rancher and dabbled in local

politics, being elected to the tribal council in 1957. In 1960 he was

diagnosed with diabetes. In 1961, however, Khama leapt back onto the political scene by founding the nationalist Bechuanaland Democratic Party. His exile gave him an increased credibility with an independence minded electorate, and the BDP swept aside its Socialist and Pan-Africanist rivals to dominate the 1965 elections. Now Prime Minister of Bechuanaland, Khama continued to push for Botswana's independence, from the newly established capital of Gaborone. A 1965 constitution delineated a new Botswana government, and on 30 September 1966, Botswana gained its independence, with Khama acting as its first President. In 1966 Elizabeth II appointed Khama Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. At

the time of its independence, Botswana was among the world’s poorest

countries, even poorer than most other African countries. Khama set out on a vigorous economic programme intended to transform it into an export based economy, built around beef, copper and diamonds. The 1967 discovery of Orapa’s diamond deposits aided this programme. However, other African countries have had abundant resources and still proved poor. Between 1966 and 1980 Botswana had the fastest growing economy in the world. Much of this money was reinvested into infrastructure, health, and education costs, resulting in further economic development. Khama also instituted strong measures against corruption,

the bane of so many other newly independent African nations. Unlike

other countries in Africa, his administration adopted market friendly

policies to foster economic development. Khama promised low and stable

taxes to mining companies, liberalized trade, and increased personal freedoms. He maintained low marginal income tax rates to deter tax evasion and corruption. He upheld liberal democracy and non-racialism in the midst of a region embroiled in civil war, racial enmity and corruption. On

the foreign policy front, Khama exercised careful politics and did not

allow militant groups to operate from within Botswana. According to

Richard Dale "The Khama government had authority to do so by virtue of

the 1963 Prevention of Violence Abroad act, and a week after

independence, Sir Seretse Khama announced before the National Assembly

his government’s policy to insure that Botswana would not become a base

of operations for attacking any neighbor." Shortly before his death, Khama would play a major role in negotiating the end of the Rhodesian civil war and the resulting creation and independence of Zimbabwe. On a personal level, he was known for his intelligence, integrity and sense of humour.

Khama remained president until his death from

pancreatic cancer in 1980, when he was succeeded by Vice President Quett Masire. Forty thousand people paid their respects while his body lay in state in Gaborone. He was buried in the Khama family graveyard on a hill in Serowe, Central District. Twenty - eight years after Khama's death, his son Ian succeeded Festus Mogae as the fourth President of Botswana; in the 2009 general election he won a landslide victory in which a younger son, Tshekedi Khama, was elected as a parliamentarian from Serowe North West.