<Back to Index>

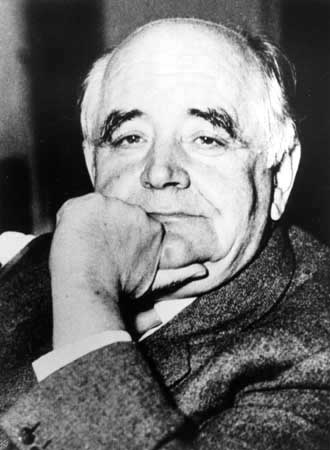

- Historian Michele Amari, 1806

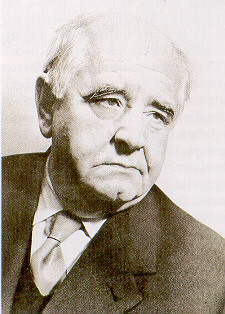

- Writer Miroslav Krleža, 1893

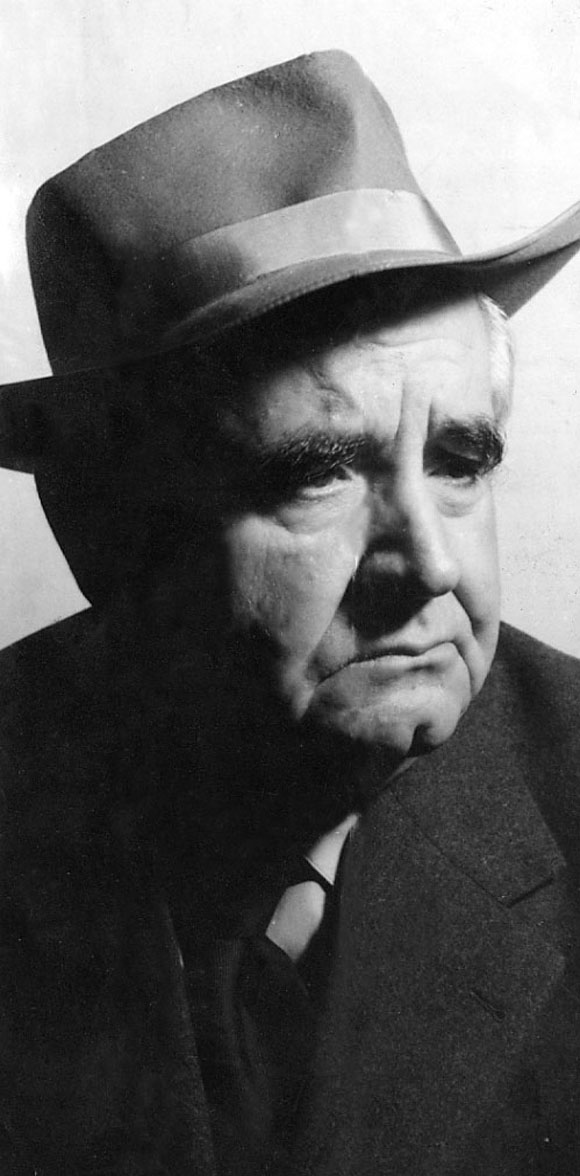

- Last President of the Reichsgericht Erwin Konrad Eduard Bumke, 1874

PAGE SPONSOR

Miroslav Krleža (July 7, 1893 - December 29, 1981) was a leading Croatian and Yugoslav writer and the dominant figure in cultural life of both Yugoslav states, the Kingdom (1918 – 1941) and the Republic (1945 until his death in 1981). He has often been proclaimed the greatest Croatian writer of the 20th century.

Miroslav Krleža was born in Zagreb, modern day Croatia. He entered a preparatory military school in Pécs, modern day Hungary. At that time, Pécs and Zagreb were within the Austro - Hungarian Empire. Subsequently, he attended the Ludoviceum military academy at Budapest. He defected for Serbia in 1912 as a volunteer for the Serbian army, but was dismissed as a suspected spy. Upon his return to Croatia, he was demoted in the Austro - Hungarian army and sent as a common soldier to the Eastern front in the World War I. In the post - World War I period Krleža established himself both as a major Modernist writer and politically controversial figure in Yugoslavia, a newly created country which encompassed South Slavic lands of former Habsburg Empire and the kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro.

Krleža was the driving force behind Leftist literary and political reviews Plamen (1919), Književna republika (1923 – 1927), Danas (1934) and Pečat (1939 – 1940). He was a member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia from 1918, expelled in 1939 because of his unorthodox views on art, his defense of artistic freedom against Socialist realist doctrine, and his unwillingness to give an open support to Stalin's purges, after the long polemic now known as "the Conflict on the Literary Left", lead between Krleža and virtually every important writer in the mid-war Yugoslavia. The Party commissar sent to intermediate between Krleža and other Leftist and Party journals was Josip Broz Tito. After the establishment of the pro-Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia, Krleža refused to join the Partisans now headed by Tito. It is believed that Krleža made that decision after learning of what happened to his associate August Cesarec in the Kerestinec incident, fearing the possible revenge from his former Party colleagues. Krleža spent the war period in Zagreb, marginalized by the Nazi government as he refused their calls for cooperation. During these years he kept silent, not publishing at all or making public appearances.

Following a brief period of social stigmatization after 1945 - during which he nevertheless became a very influential vice - president of Yugoslav Academy of Science and Arts in Zagreb, while Croatia's central state publishing house, Nakladni zavod Hrvatske, published his collected works - Krleža was rehabilitated after Yugoslavia's break-up with Stalin's SSSR, while his position on art and literature even became the official one. Still, Milovan Đilas publicly defended the Party's pre-war position against Krleža, declaring that his magazine Pečat worked from the revisionist positions, but on Tito's intervention, "the Conflict on Literary Left" was officially closed and Đilas' speech was regarded as a personal opinion, and was not printed in the proceedings of the Party's 1948 congress.

Supported by Tito, in 1950 Krleža founded the Yugoslav Institute for Lexicography, holding the position of its head until his death. The institute would become posthumously named after him, and is now called the Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute.

From 1950 on, Krleža led the life of a high profile writer and intellectual, often closely connected to President Tito. Krleža wrote about Tito that Tito was an illegitimate child of Keglević who became in another poem as a fictional character the epitome of exploitation of the working class. He also shortly held the post of the president of Yugoslav writers' union between 1958 and 1961. In 1962 he received the NIN award for the novel Zastave, and in 1968 the Herder Prize.

Following

the deaths of Tito in May 1980, and particularly of Krleža's wife Bela

Krleža in April 1981, Krleža spent most of his last year of life

depressed and ill. He was awarded Laureate Of The International Botev Prize in

1981. He died in his villa Gvozd in Zagreb, on December 29, 1981, at 1

am, and received a state funeral in Zagreb on January 4, 1982. Gvozd is

now his memorial center. However

interesting Krleža's political and social stance toward various

ideological and political events may be, his enduring legacy is as one

of the finest European modernist authors — a fact frequently

overlooked, not least due to his turbulent political career and general

influence on cultural life in Yugoslavia. Miroslav Krleža's collected

works number more than 50 volumes and cover all parts of imaginative

literature: poetry, drama, short story, novels, essays, diaries,

polemics and autobiographical prose. He is the heir of two parallel traditions: a specifically Croatian one, where he conceived of his role in the Croatian literature as the shaper of national consciousness, or, in terms of James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: "to forge in the smithy of his soul the uncreated conscience of his race"; the other one is the broad European avant garde movement. Krleža's formative influences include Scandinavian drama, French Symbolism and Austrian and German expressionism and modernism, with key authors like Ibsen, Strindberg, Nietzsche, Karl Kraus, Rilke and Proust.

Although Krleža's lyric poetry is held in high regard, by common critical consensus his greatest poetic work is Balade Petrice Kerempuha (Ballads of Petrica Kerempuh), a visionary compendium of Golgotha Croatica, spanning more than five centuries and centred around the figure of plebeian prophet Petrica Kerempuh, a sort of Croatian Till Eulenspiegel. This sombre and highly complex multilayered poem evoking reminiscences on Bruegel and Bosch paintings, written in a unique hybrid language based on Croatian kajkavian dialect interspersed

with Latin, German, Hungarian and archaic Croatian highly stylised

idiom, irradiates universal dark verities on human condition epitomized

in Croatian historical experience. Krleža's novelistic opus consists of four novels: Povratak Filipa Latinovicza (The Return of Filip Latinovicz), Na rubu pameti (On the Edge of Reason), Banket u Blitvi (The Banquet in Blitva) and Zastave (The Banners). All four novels exemplify characteristics of Krleža's narrative prose: highly eloquent, almost baroque style;

expressionist innovations and techniques integrated in a mature

authorial voice; numerous essayist passages that define these works as

novels of ideas; a blend of existentialist vision and sharp consciousness of politics as the determining factor of human lives. The

first one is a novel about an artist, written in the Proustian mood,

but forecasting the existentialist shadow, a novel written quite some

time before Sartre's Nausea and yet unrecognized as such; On the Edge of Reason and The Banquet in Blitva are essentially political - satirical novels of ideas (the latter located in an imaginary Baltic country and called a political poem), saturated with an atmosphere of all - pervading totalitarianism, while The Banners has been rightly dubbed a "Croatian War and Peace".

It is a multivoluminous panoramic view of Croatian (and Central

European) society before, during, and after World War I, revolving

around the prototypical theme of fathers and sons in conflict. All Krleža's novels except the last one, Zastave (The Banners), have been translated into English.

Miroslav

Krleža's essays contain both his best and his worst writing.

Undoubtedly the literary form he had found the most genial to his

artistic temperament, Krleža has poured into essays everything that

provoked his intelligence and sensibility — this genre covers more than

20 books of his collected works. Encyclopedic knowledge and polemical

passion inform his meditations on various aspects and personalities of

culture (Marcel Proust, Baudelaire, Erasmus, Paracelsus), political anatomies of history both contemporary and medieval (Deset krvavih godina (Ten bloody years), Amsterdamske varijacije), vignettes on art and music (Chopin, Grosz) - all is covered in this veritable anatomy of European history and culture.

The most notable collection of Krleža's short stories is the anti-war book Hrvatski bog Mars (Croatian god Mars), on the fates of Croatian soldiers sent to the slaughterhouse of World War I battlefields.

Krleža's main artistic interest was centered around drama. He began with experimental expressionist plays like Adam i Eva and Michelangelo Buonarroti,

dealing with defining passions of heroic figures, but eventually opted

for a more conventional naturalist drama, patterned along examples of

mature works by Ibsen and Strindberg.

The best known is his cycle dealing with the decay of a bourgeois

family sunken in the morass of adultery, corruption, theft and murder, Gospoda Glembajevi. Also of note is Golgota, a political drama. As is the case in some of his poetry and short stories, in Golgota Krleža

again deals with biblical symbols and figures, but in a very earthly

way, leading towards a finale reminiscent of Strindberg's Father.

Krleža's memoirs and diaries (especially Davni dani (Olden days) and Djetinjstvo u Agramu (Childhood

in Zagreb)) are fascinating documents of growing and expanding

self - awareness grappling with the world outside and mutable inner self.

Other masterpieces, like Dnevnici (Diaries) and posthumously published Zapisi iz Tržiča (Notes

from Tržič) chronicle multifarious impressions (aesthetic, political,

literary, social, personal, philosophical) that an inquisitive

consciousness has recorded during an era that lasted more than half a

century.