<Back to Index>

- Aircraft Manufacturer Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin, 1838

- Painter Pavel Dmitriyevich Korin, 1892

- 1st President of Portugal Manuel José de Arriaga Brum da Silveira e Peyrelongue, 1840

PAGE SPONSOR

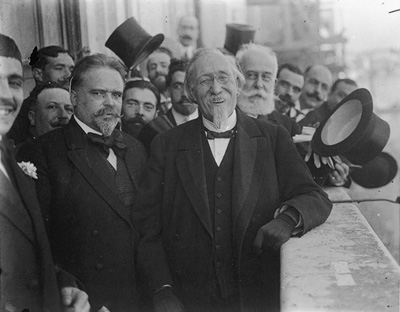

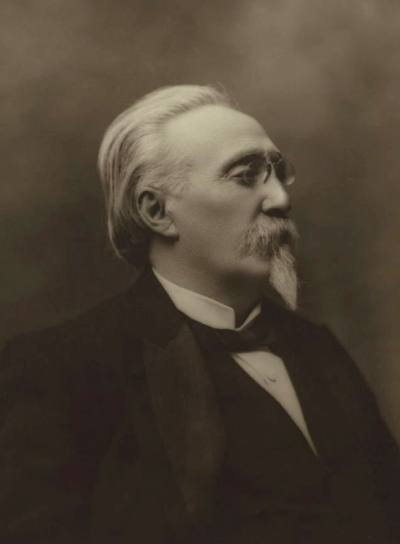

Manuel José de Arriaga Brum da Silveira e Peyrelongue (Horta, July 8, 1840 - Santos-o-Velho, Lisbon, March 5, 1917) was a Portuguese lawyer, the first Attorney - General and the first elected President of the First Portuguese Republic, following the abdication of King Manuel II of Portugal and a Republican Provisional Government headed by Teófilo Braga (who would succeed him in the post following his resignation).

Of his early life details are brief: Arriaga was born to an aristocratic family; son of Sebastião José de Arriaga Brum da Silveira (c. 1810 - Setúbal, 18 October 1881) and wife (m. 24 December 1834) Maria Cristina Pardal Ramos Caldeira (c. 1815 - ?). Arriaga's father was a rich merchant in the city, only son, and property owner, whose heritage traced his lineage to the Flem Joss van Aard, one of the original settlers of the island of Faial (of the male line to a Basque family of small nobility) and whose second cousin was Bernardo de Sá Nogueira de Figueiredo, 1st Marquess of Sá da Bandeira. The young Manuel was also the grandson of General Sebastião José de Arriaga Brum da Silveira, who distinguished himself in the Peninsular Wars, and grand - nephew of the Judge of the Supreme Court, who between 1821 and 1822 was also a representative for the Azores in the Constituent Courts.

The Arriaga family included six children, of these the following siblings: Maria Cristina, the oldest (a poet, referred by Vitorino Nemésio in his obra - prima Mau Tempo no Canal); José de Arriaga, a historian (known for História da Revolução Portuguesa de 1820, published in 1889 and Os Últimos 60 anos da Monarquia ,

published in 1911); Sebastião Arriaga Brum da Silveira

Júnior, agricultural engineer (after studying abroad, he worked

on land recuperation projects in the Alentejo); and Manuel, the fourth in line of succession (who decided early on to concentrate on politics). Around the age of 18, he moved with his younger brother (José de Arriaga) to Coimbra to study at the University of Coimbra in

the Faculty of Law (from 1860 to 1865), where he distinguished himself

for his brilliant mind and notable oratory. During this time he adhered to philosophical positivism and republican democracy,

where he frequently joined others in discussions on philosophy and

politics, showing a capacity for argument and imagination. His

republican idealism, considered subversive, caused a rift between him

and his conservative monarchist leaning father (a supporter of the

traditionalist King D. Miguel);

his father would break-off ties with his sons (for those subversive

ideals), forcing the older Manuel to work to support his and his

brother's studies. He taught English classes at the local secondary

school. His brother wrote in various newspapers in Coimbra and Lisbon,

showing himself a proficient writer of science and philosophy. In 1866, he competed for the 10th chair at the Escola Politécnica (Polytechnical

school), as well as the chair in History in the department of Letters.

Unsuccessful, he continued in Lisbon as an English teacher. Later, he

established a legal practice, and quickly developed a clientele, which

permitted him the financial security to assist his brother in

completing his studies. Between many of the causes he defended while a

lawyer, in 1890, he was the advocate for António José de Almeida, after he wrote "Bragança, o último" a treatise against King D. Carlos in the academic journal O Ultimatum. Ten years later, on August 26, 1876, he joined the Comissão para a Reforma da Instrução Secundária ("Commission on the Reform on Secondary School Instruction"). A member of the Portuguese Republican Party (before January 31, 1891), alongside Jacinto Nunes, Azevedo e Silva, Bernardino Pinheiro, Teófilo Braga and Francisco Homem Cristo, he was an active parliamentarian during the constitutional monarchy of King Luís I;

he was involved in the debates on the reform of education, the penal

code and prisons, in addition to electoral reform. By this time doctrinaire republicans had been replaced by others in

the party affiliated with masonry or the nascent Carbonari associations. He was also elected deputy for Funchal (1883 – 84) in the minority

Republican government and later Lisbon (1890 – 92). A pragmatist, he

actively promoted the Republican cause, while maintaining good

relations with the Roman Catholic Church,

unlike some of his contemporaries in the Republican movement. But, at

the same time, he was combative and critical of what he saw as the

"lethargy of monarchical governments, the [general] wastes and luxuries

of the royal family. Yet,

he ardently denounced irregularities in his own government, especially

when some Ministers transferred funds from the government coffers into

private hands. Following

the establishment of the Republic (October 5, 1910), young Republican

students in Coimbra entered the buildings of the Senate, and

vandalized the Hall and furniture used in Doctoral ceremonies and

damaged paintings of the last Portuguese kings. In order "to

impede other depravities Dr. António José de Almedia

(Republican from the first hour) invited Dr. Manuel de Arriaga to be

rector of the old University and gave him leave on 17 October of 1910

in a ceremony without academic ceremonies, which was enough to curb

student enthusiasm". During the period of the Provisional Government, he became the Attorney - General of the Republic premièring in that way a paladin of Republican propaganda and as one of the more caustic Portuguese. As

one of the older figures of the Republican regime (he was 71), he was

elected President on August 24, 1911; he did not campaign for the

position, and noted that it was a heavy burden, which he believed he

was personally incapable of fulfilling its duties, but accepted it "for

the good of the Republic". The other candidate was Dr. Bernardino Machado (who would also become President later), but it was António José de Almeida who had suggested Manuel Arriaga at the end of Teófilo Braga's Provisional Government. As Almeida had believed Arriaga "was one of the few, if not the only man in the Party who worked well with everyone and whom the Lord Christ didn't speak ill" The

Presidency was itself not an enviable or prestigious position; although

the elected person, for a time, occupied a large home in Horta Seca,

they were required to furnish the home at their own cost, pay rent and

had no transport budget, nor personal secretary (Arriaga would ask his

own son to help him in this role). Later, the first President lived in

the Palace of Belém, but not in the main building, but rather an

annex off of the Pátio das Damas. This occurred in a period when

personal divisions between different factions had splintered the

Republican cause; António José de Almeida would form the Evolutionist Party, Brito Camacho the Republican Union, while Afonso Costa would

continue to front the main Republican Party (renamed the Democratic

Party). Manuel de Arriaga, for his part, would select the politician

and journalist João Chagas to

head his first government. In his personal autobiography, Arriaga

recounted how he hoped that he would not be another factor to divide

Republicans, especially in a time where there existed a need to work

together; it was a difficult period historically, due to the

exasperation of the "religious question", constant social agitation and

political party instability (associated with "Machiavellian strategies"

of some politicians) that fermented during the infancy of the First

Republic. Frequently, Arriaga was unable to contain these tensions and

often had to deal with counter - revolutionary revolts, such as the Royalist attack on Chaves led by Captain Paiva Couceiro.

During his mandate, several governments fell; there were eight changes

in the Prime Minister's office, disorder in the streets, violent

reactions against the church, as well as counter - revolutionary

monarchist movements. Finally, he invited Dr. António

José de Almeida to lead the government, but he refused, and

opted for the Republican Afonso Costa,

who would govern off-and-on until 1917. Hated, but feared, he governed

and even sought to restore some order and economy to the public

accounts. Although

Afonso Costa was able to reduce the deficit, the instability and

conflict between Parties persisted, made more critical by internal

politics and growing international tensions in 1914 (that would

eventually begin the Great War). Arriaga

deplored the circumstances, going so far as to announcing his intent to

resign unless a coalition or non-party government could be installed

that resolved the outstanding issues of amnesty and separation of

church and state. But,

subsequent governments would not resolve the issue immediately; on

February 22, 1914 an amnesty was conceded for those not accused of

violent actions, and eleven leaders of subversive groups were released,

but the Law of Separation remained unrevised. The

new Republic was now increasingly unmanageable, and further, there were

divergences developing between the government and the army. At one

point, a military contingent in Oporto attempted a coup d'état

in Lisbon, which was suppressed. The government suggested disbanding

the regiments involved, but their leaders appealed to General

Pimenta de Castro.

In an attempt to mitigate these problems, Manuel de Arriaga wrote to

the three party leaders (Camacho, Afonso Costa and António

José de Almeida) in order to come to an accord and form a unity

government, but Afonso Costa did not react well to the proposal. The President then withdrew his support for the government, then - presided by Vítor Hugo de Azevedo, and to calm the Army called on General Joaquim Pimenta de Castro (who

had been the Minister of War under João Chagas) to form a

government. Arriaga had known and placed his confidence in Castro. But,

Joaquim Pereira Pimenta de Castro selected for his ministers, seven

military officers, who did not permit the re-opening of Parliament, and

provided an amnesty for convicted monarchists involved in the Attack on Chaves. He made changes to electoral law and began governing as a dictator, which was only supported by the Evolutionist Party (Portugal) and the group led by Machado dos Santos on the political right of the Republicans. What

had started as an attempt to eliminate an inevitable conflict between

the armed forces and the political class, eventually resulted in a

bloody conflict. The parliamentarians, meeting secretly on May 4, 1915

in the Palácio da Mitra, declared Arriaga and Pimenta de Castro

outside the law, their acts undemocratic and essentially void. Then, on

May 14, in a revolt instigated

by members of the Democratic Party, elements of civil reactionary

groups and supported by elements of the Navy began what was essentially a civil war;

there were many deaths and injuries on both sides. The well intentioned

and pacifist Arriaga had only one option; twelve days following the

start of the uprising, he resigned from the Presidency. In his

resignation letter, he stated that the deaths during the revolt were

needless, that Pimenta de Castro's regime was less a dictatorship than

earlier governments and that 1914 - 15 laws had given future governments

unusual war powers. He paid heavily for his political naivety; as the author Raul Brandão noted the man although profoundly altruistic and magnanimous, good - natured and honorable had rapidly turned into a political criminal and

accused of duplicity with the dictatorial and violent Pimenta de

Castro. In his resignation (to his ministers and Party) he defended

himself against these unjust accusations and declared his

well - intentioned loyalty to the Republican cause, which he had

supported throughout his life (but which had abandoned him

disillusioned). The parliamentarian, writer and journalist, Augusto de

Castro later recounted a conversation with the former President,

shortly before his death (in 1917): But

August de Castro ended his story by noting that upon leaving the

ex-President's home he purchased a newspaper that referred to Arriaga

as a renegade and traitor, and thought, "never, like that afternoon, did politics seem so cruel and a sinister thing". Manuel de Arriaga was replaced as President by Professor Teófilo Braga in 1915, who had led the provisional government following the abdication and exile of King Emanuel II. At the age of 30, Arriaga had married Lucrécia Augusta de Brito de Berredo Furtado de Melo (Foz do Douro, Porto, November 13, 1844 - Parede, Oeiras, October 14, 1927), from a family friendly to the Arriagas (from the island of Pico).

The ceremony occurred in a chapel near Valença do Minho, where

her father was General and Governor. For a few years the couple lived

in Coimbra, where Manuel de Arriaga flourished in his law practice. Six

children were born, two boys and four girls, and the family regularly

spent their holidays in Buarcos. Following

his resignation, Manuel de Arriaga died in Lisbon two years later. His

home in Lisbon, near Rua da Janelas Verdes, overlooked the boats in the Tejo, and in the room where he died there were photographs of the two men he most admired, Victor Hugo and Alexandre Herculano while

above his bed, an image of Christ. In the end, former President

Arriaga's image was rehabilitated by the Portuguese media for his intelligence, patriotism, benevolence and his honor for the manner in which he exercised his functions. This was further enhanced by the publication of his papers and documents, as well as the work of several intellectuals.

Continuing political intrigues inevitably forced the first Republic down the path

towards dictatorship. At the onset of the First World War, there was

also pressure from the Portuguese colonies in Africa, principally

Angola and Mozambique and the National Assembly had decided, while

remaining initially neutral in the conflict, to send troops to those

colonies which fronted German possessions.