<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Joseph Arthur Comte de Gobineau, 1816

- Folk Songwriter Woodrow Wilson "Woody" Guthrie, 1912

- Anarchist Revolutionary José Buenaventura Durruti Dumange, 1896

PAGE SPONSOR

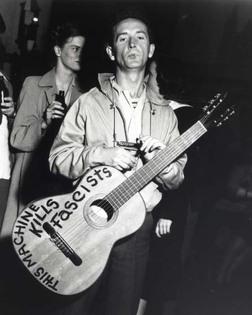

Woodrow Wilson "Woody" Guthrie (July 14, 1912 – October 3, 1967) is best known as an American singer - songwriter and folk musician, whose musical legacy includes hundreds of political, traditional and children's songs, ballads and improvised works. He frequently performed with the slogan This Machine Kills Fascists displayed on his guitar. His best known song is "This Land Is Your Land". Many of his recorded songs are archived in the Library of Congress. Such songwriters as Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Bruce Springsteen, Pete Seeger, Joe Strummer and Tom Paxton have acknowledged their debt to Guthrie as an influence.

Guthrie

traveled with migrant workers from Oklahoma to California and learned

traditional folk and blues songs. Many of his songs are about his

experiences in the Dust Bowl era during the Great Depression, earning him the nickname the "Dust Bowl Troubadour". Throughout his life Guthrie was associated with United States communist groups, though he was allegedly not a member of any. Guthrie was married three times and fathered eight children, including American folk musician Arlo Guthrie. He is the grandfather of musician Sarah Lee Guthrie. Guthrie died from complications of Huntington's disease, a progressive genetic neurological disorder. During his later years, in spite of his illness, Guthrie served as a figurehead in the folk movement, providing inspiration to a generation of new folk musicians, including mentor relationships with Ramblin' Jack Elliott and Bob Dylan. Woody Guthrie was inducted into the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame in 1997.

Guthrie was born in Okemah, a small town in Okfuskee County, Oklahoma, to Nora Belle Tanner and Charles Edward Guthrie. His parents named him after Woodrow Wilson, then Governor of New Jersey and the Democratic candidate soon to be elected President of the United States. Charles Guthrie was an industrious businessman, owning at one time up to 30 plots of land in Okfuskee County. He was actively involved in Oklahoma politics and was a Democratic candidate for office in the county. When Charles was making stump speeches, he would often be accompanied by his son. Charles Guthrie was involved in at least one lynching during his time in Okemah, Oklahoma, the lynching of Laura and Lawrence Nelson. Guthrie's early family life was affected by several tragic fires, including one that caused the loss of his family's home in Okemah. His sister Clara later died in a coal - oil fire when Guthrie was seven, and Guthrie's father was severely burned in a subsequent coal - oil fire. The circumstances of these fires, especially those in which Charley was injured, remain unclear. It is unknown whether they were simple accidents or the result of actions by Guthrie's mother who, unknown to the Guthries at the time, was suffering from Huntington's disease. Nora Guthrie was eventually committed to the Oklahoma Hospital for the Insane, where she died in 1930 from Huntington's disease. It is also suspected that her father, George Sherman, judging from the circumstances surrounding his death by drowning, suffered from the same hereditary disease.

With Nora Guthrie institutionalized and Charley Guthrie living in Pampa, Texas, and working to repay his debts from unsuccessful real estate deals, Woody Guthrie and his siblings were on their own in Oklahoma and relied on their eldest brother, Roy Guthrie, for support. The 14 year old Guthrie worked odd jobs around Okemah, begging meals and sometimes sleeping at the homes of family friends. According to one story, Guthrie made friends with an African - American blues harmonica player named "George", who he would watch play at the man's shoe shine booth. Before long, Guthrie bought his own harmonica and began playing along with him. However, in another interview 14 years later, Guthrie claimed he learned how to play harmonica from a boyhood friend, John Woods, and that his earlier story about the shoe shining player was false. He seemed to have a natural affinity for music and easily learned to "play by ear". He began to use his musical skills around town, playing a song for a sandwich or coins. Guthrie easily learned old Irish ballads and traditional songs from the parents of friends. Although he did not excel as a student (he dropped out of high school in his fourth year and did not graduate), his teachers described him as bright. He was an avid reader on a wide range of topics. Friends recall his reading constantly.

Eventually, Guthrie's father sent for his son to come to Texas where little would change for the now aspiring musician. Guthrie, then 18, was reluctant to attend high school classes in Pampa and spent much time learning songs by busking on the streets and reading in the library at Pampa's city hall. He was growing as a musician, gaining practice by regularly playing at dances for his father's half - brother Jeff Guthrie, a fiddle player. At the library, he wrote a manuscript summarizing everything he had read on the basics of psychology. A librarian in Pampa shelved this manuscript under Guthrie's name, but it was later lost in a library reorganization.

At age 19, Guthrie met and married his first wife, Mary Jennings, with whom he had three children, Gwendolyn, Sue and Bill, all of whom would later die prematurely. With the advent of the Dust Bowl era, Guthrie left Texas, leaving Mary behind, and joined the thousands of Okies who were migrating to California looking for work. Many of his songs are concerned with the conditions faced by these working class people.

In the late 1930s, Guthrie achieved fame in Los Angeles, California, with radio partner Maxine "Lefty Lou" Crissman as a broadcast performer of commercial "hillbilly" music and traditional folk music. Guthrie was making enough money to send for his family still living in Texas. While appearing on the commercial radio station KFVD, owned by a populist minded New Deal Democrat Frank Burke, Guthrie began to write and perform some of the protest songs that would eventually appear on Dust Bowl Ballads. It was at KFVD that Guthrie met newscaster Ed Robbin. Robbin was impressed with a song Guthrie wrote about Thomas Mooney, believed by many to be a wrongly convicted man who was, at the time, a leftist cause célèbre. Robbin, who became Guthrie's political mentor, introduced Guthrie to socialists and communists in Southern California, including Will Geer, who would remain Guthrie's lifelong friend, and helped Guthrie book benefit performances in the communist circles in Southern California. Notwithstanding Guthrie's later claim that "the best thing that I did in 1936 was to sign up with the Communist Party", he was never actually a member of the Party. He was, however, noted as a fellow traveler — an outsider who agreed with the platform of the party while not subject to party discipline. Despite this, Guthrie requested that he be allowed to write a column for the Communist newspaper The Daily Worker. The column, titled "Woody Sez", appeared a total of 174 times from May 1939 to January 1940. Woody Sez was not explicitly political, but rather was about the current events Guthrie observed and experienced. The columns were written in an exaggerated hillbilly dialect and usually included a small comic, and were published as a collection after Guthrie's death. Steve Earle said of Woody, "I don't think of Woody Guthrie as a political writer. He was a writer who lived in very political times".

With the outbreak of World War II and the nonaggression pact the Soviet Union had signed with Germany in 1939, the owners of KFVD radio did not want its staff "spinning apologia" for the Soviet Union, and both Robbin and Guthrie left the station. Without the daily radio show, prospects for employment diminished, and Guthrie and his family returned to Pampa, Texas. Although Mary Guthrie was happy to return to Texas, the wander lusting Guthrie soon after accepted Will Geer's invitation to come to New York City and headed east.

Arriving in New York, Guthrie, known as "the Oklahoma cowboy", was embraced by its leftist folk music community and slept on a couch in Will Geer's apartment. Guthrie made what were his first real recordings — several hours of conversation and songs that were recorded by folklorist Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress — as well as an album, Dust Bowl Ballads, for Victor Records in Camden, New Jersey.

Guthrie was tired of the radio overplaying Irving Berlin's "God Bless America". He thought the lyrics were unrealistic and complacent. Partly inspired by his experiences during a cross country trip and his distaste for God Bless America, he penned his most famous song, "This Land Is Your Land", in February 1940; it was subtitled "God Blessed America." The melody is adapted from an old gospel song "Oh My Loving Brother", best known as "When The World's On Fire", sung by the country group The Carter Family. Guthrie signed the manuscript with the comment "All you can write is what you see, Woody G., N.Y., N.Y., N.Y.". He protested against class inequality in the fourth and sixth verses:

- As I went walking, I saw a sign there,

- And on the sign there, It said "no trespassing." [In another version, the sign reads "Private Property"]

- But on the other side, it didn't say nothing!

- That side was made for you and me.

- In the squares of the city, In the shadow of a steeple;

- By the relief office, I'd seen my people.

- As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

- Is this land made for you and me?

These verses were often omitted in subsequent recordings, sometimes by Guthrie himself. Although the song was written in 1940, it was four years before he recorded it for Moses Asch in April 1944, and even longer until sheet music was produced and given to schools by Howie Richmond.

In March 1940, Guthrie was invited to play at a benefit hosted by The John Steinbeck Committee to Aid Farm Workers to raise money for migrant workers. It was at this concert Guthrie met Pete Seeger, and the two men became good friends. Later, Seeger accompanied Guthrie back to Texas to meet other members of the Guthrie family and later recalled an awkward conversation with Mary Guthrie's mother in which she asked for Seeger's help in persuading Guthrie to treat her daughter better.

Guthrie had some success in New York at this time as a guest on CBS's radio program Back Where I Come From and used his influence to get a spot on the show for his friend Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter. Ledbetter's Tenth Street apartment was a gathering spot for the left wing musician circle in New York at the time, and Guthrie and Ledbetter were good friends having busked together at bars in Harlem.

In September 1940 Guthrie was invited by the Model Tobacco Company to host their radio program "Pipe Smoking Time". Guthrie was paid $180 a week, an impressive salary in 1940. He was finally making enough money to send regular payments back to Mary, and eventually brought her and the children to New York, where the family lived in an apartment on Central Park West. The reunion represented Woody's desire to be a better father and husband. He said "I have to set [sic] real hard to think of being a dad". Unfortunately for the newly relocated family, Guthrie quit after the seventh broadcast, claiming he had begun to feel the show was too restricting when he was told what to sing. Disgruntled with New York, Guthrie packed up Mary and his children in a new car and headed west to California.

In May 1941, after a brief stay in Los Angeles, Guthrie moved the family north to Washington state on the promise of a job. A documentary, directed by Gunther von Fritsch, was being created in support of the Bonneville Power Administration's building of the Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River, and needed a narrator. Supported by a recommendation from Alan Lomax, the original idea was to have Guthrie narrate the film and sing songs onscreen. The original project was expected to take 12 months, but when filmmakers became worried about the implications of casting such a political figure, Guthrie's role was minimized. He was hired instead for one month only by the Department of the Interior to write songs about the Columbia River and the building of the federal dams for the documentary's soundtrack. While there, Guthrie toured the Columbia River and the Pacific Northwest. Guthrie said he "couldn't believe it, it's a paradise", which appeared to inspire him creatively. In one month Guthrie wrote 26 songs, including three of his most famous: "Roll On Columbia", "Pastures of Plenty", and "Grand Coulee Dam". The surviving songs were eventually released as Columbia River Songs. The film was never completed and was released only in a limited form.

At the conclusion of the month in Oregon and Washington, Guthrie wanted to return to New York. Tired of the continual uprooting, Mary Guthrie told him to go without her and the children. Although Guthrie would see Mary again, once on a tour through Los Angeles with the Almanac Singers, it was essentially the end of their marriage. Divorce was difficult, since Mary was a member of the Catholic Church, but she reluctantly agreed in December 1943.

Following the conclusion of his work in Washington State, Guthrie corresponded with Pete Seeger about Seeger's newly formed folk protest group, the Almanac Singers. Guthrie returned to New York with plans to tour the country as a member of the group. The singers originally worked out of a loft in New York City hosting regular concerts called hootenannys, a word Pete and Woody had picked up in their cross country travels. The singers eventually outgrew the space and moved into the cooperative Almanac House in Greenwich Village.

Initially Guthrie helped write and sing what the Almanacs Singers termed "peace" songs; while the Nazi - Soviet Pact was in effect, until Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Communist line was that World War II was a capitalist fraud. After Hitler's invasion of the Soviet Union the topics of their songs became anti - fascist. The members of the Almanac Singers and residents of the Almanac House were a loosely defined group of musicians, though the 'core' members included Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Millard Lampell and Lee Hays. In keeping with common socialist ideals, meals, chores and rent at the Almanac House were shared. The Sunday hootenannys were good opportunities to collect donation money for rent. Songs written in the Almanac House had shared songwriting credits among all the members, although in the case of "Union Maid", members would later state that Guthrie wrote the song, ensuring that his children would receive residuals.

In the Almanac House Guthrie added an air of authenticity to their work since Guthrie was a "real" working class Oklahoman. "There was the heart of America personified in Woody.... And for a New York Left that was primarily Jewish, first or second generation American, and was desperately trying to get Americanized, I think a figure like Woody was of great, great importance", a friend of the group, Irwin Silber, would say. Woody would routinely emphasize his working class image, reject songs he felt were not in the country blues vein he was familiar with, and would rarely contribute to household chores. House member Agnes "Sis" Cunningham, another Okie, would later recall that Woody, "loved people to think of him as a real working class person and not an intellectual". Guthrie contributed songwriting and authenticity in much the same capacity for Pete Seeger's post-Almanac Singers project People's Songs, a newsletter and booking organization for labor singers, founded in 1945.

Guthrie

was a prolific writer, penning thousands of pages of unpublished poems

and prose, many written while living in New York City. After a

recording session with Alan Lomax, Lomax suggested Guthrie write an

autobiography; in Lomax's opinion, Guthrie's descriptions of growing up

were some of the best accounts of American childhood he had read. It was during this time that Guthrie met the dancer in New York who would become his second wife, Marjorie Mazia. Mazia was an instructor at the prestigious Martha Graham Dance School, where she was assisting Sophie Maslow with her piece Folksay. Based on the folklore and poetry collected by Carl Sandburg, Folksay included the adaptation of some of Guthrie's Dust Bowl Ballads for the dance studio. Guthrie continued to write songs and began work on his autobiography. The end product, Bound For Glory was completed in no small part due to the patient editing assistance of Mazia and was first published by E.P. Dutton in 1943. It is a vivid tale told in the artist's own down home dialect, with the flair and imagery of a true storyteller. Library Journal complained about the "Too careful reproduction of illiterate speech." But Clifton Fadiman, reviewing the book in the New York Times,

paid the author a fine tribute: "Some day people are going to wake up

to the fact that Woody Guthrie and the ten thousand songs that leap and

tumble off the strings of his music box are a national possession like

Yellowstone and Yosemite, and part of the best stuff this country has to show the world." A film adaptation of Bound for Glory was released in 1976.

Guthrie believed performing his anti - fascist songs and poems at home were the best use of his talents; Guthrie lobbied the United States Army to accept him as a USO performer instead of conscripting him as a soldier in the draft. When Guthrie's attempts failed, his friends Cisco Houston and Jim Longhi pressured Guthrie to join the U.S. Merchant Marine. Guthrie followed their advice: he served as a mess man and dishwasher, and frequently sang for the crew and troops to buoy their spirits on transatlantic voyages. Guthrie made attempts to write about his experience in the Merchant Marine, but was never satisfied with the results. Longhi later wrote about these experiences in his book Woody, Cisco and Me. The book offers a rare first-hand account of Guthrie during his Merchant Marine service. In 1945, Guthrie's association with communism made him ineligible for further service in the Merchant Marine, and he was drafted into the U.S. Army.

While he was on furlough from the Army, Guthrie and Marjorie were married. After his discharge, they moved into a house on Mermaid Avenue in Coney Island, and over time had four children. One of their children, Cathy, died as a result of a fire at age four, sending Guthrie into a serious depression. Their other children were named Joady, Nora and Arlo. Arlo followed in his father's footsteps as a singer - songwriter. During this period, Guthrie wrote and recorded, Songs to Grow on for Mother and Child, a collection of children's music, which includes the song "Goodnight Little Arlo (Goodnight Little Darlin')", written when Arlo was about nine years old.

A 1948 crash of a plane carrying 28 Mexican farm workers from Oakland, California, in deportation back to Mexico inspired Woody to write "Deportee (Plane Wreck At Los Gatos)".

The years living on Mermaid Avenue were among Guthrie's most productive periods as a writer. His extensive writings from this time were archived and maintained by Marjorie and later his estate, mostly handled by Guthrie's daughter, Nora. Several of the manuscripts contain scribblings by a young Arlo and the other Guthrie offspring.

During this time Ramblin' Jack Elliott studied extensively under Guthrie, visiting his home and observing how he wrote and performed. Elliott, like Bob Dylan later, idolized Guthrie and was inspired by his idiomatic performance style and repertoire. Due to Guthrie's illness, Dylan and Guthrie's son Arlo later claimed they learned much of Guthrie's performance style from Elliott. When asked about Arlo's claim, Elliott said, "I was flattered. Dylan learned from me the same way I learned from Woody. Woody didn't teach me. He just said, If you want to learn something, just steal it — that's the way I learned from Lead Belly."

By the late 1940s, Guthrie's health was declining and his behavior was becoming extremely erratic. He received various diagnoses (including alcoholism and schizophrenia), but in 1952 it was finally determined that he was suffering from Huntington's disease, the genetic disorder inherited from his mother. Believing him to be a danger to their children, Marjorie suggested he return to California without her; they eventually divorced.

Upon his return to California, Guthrie lived in a compound, owned by Will Geer, with blacklisted singers and actors waiting out the political climate. As his health worsened he met and married his third wife, Anneke Van Kirk, and they had a child, Lorinna Lynn. The couple moved to Fruit Cove, Florida, briefly, living in a bus on land called Beluthahatchee, owned by a friend, Stetson Kennedy. Guthrie's arm was hurt in a campfire accident when gasoline used to start the campfire exploded. Although he regained movement in the arm, he was never able to play the guitar again. In 1954 the couple returned to New York. Shortly after, Anneke filed for divorce, a result of the strain of caring for Guthrie. Anneke left New York, allowing friends to adopt Lorina Lynn. Lorinna had no further contact with her birth parents and died in 1973 at the age of nineteen in a car accident in California. After the divorce, Guthrie's second wife, Marjorie, re-entered his life; it was Marjorie who cared for him and assisted him until his death.

Guthrie, increasingly unable to control his muscle movements, was hospitalized at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital from 1956 to 1961, at Brooklyn State Hospital until 1966, and finally at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center until his death. Marjorie

and the children visited Guthrie at Greystone every Sunday. They

answered fan mail and played on the hospital grounds. Eventually a

longtime fan of Guthrie invited the family to his nearby home for these

Sunday visits lasting until Guthrie was moved to the Brooklyn State

Hospital, which was closer to where Marjorie lived. When Bob Dylan, who

idolized Guthrie and whose early folk career was deeply inspired by

Guthrie, found out that Guthrie was hospitalized in Brooklyn, he was

determined to meet his idol. By this time Guthrie was said to have his

"good days" and "bad days". On the good days, Dylan would sing songs to

him, and at the beginning Guthrie seemed to warm to Dylan. When the bad

days came Guthrie would berate Dylan and it is said that on Dylan's

last visit Guthrie didn't recognize him. Dylan states that he made his

trek to New York City primarily to seek out his idol.

At the end of Guthrie's life he was largely alone except for family, and became hard to be around due to the progression of Huntington's. Guthrie's illness was essentially untreated, due to a lack of information about the disease at the time. However, his death helped raise awareness of the disease and led Marjorie to help found the Committee to Combat Huntington's Disease, which became the Huntington's Disease Society of America. None of Guthrie's three remaining children with Marjorie have developed symptoms of Huntington's, but two of Mary Guthrie's children (Gwendolyn and Sue) suffered from the disease (Bill died in an auto - train accident in Pomona, California, at age 23). Both died at 41 years of age.

In

the late 1950s and early 1960s, a new generation of young people were

inspired by folk singers including Guthrie. These "folk revivalists"

became more politically aware in their music than those of the previous

generation. The

American Folk Revival was beginning to take place, focused on the issues of the day, such as the civil rights movement and free speech movement. Pockets of folk singers were forming around the country in places such as Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. One of Guthrie's visitors at Greystone Park was the 19 year old Bob Dylan who

idolized Guthrie. Dylan wrote of Guthrie's repertoire: "The songs

themselves were really beyond category. They had the infinite sweep of

humanity in them." After learning of Guthrie's whereabouts, Bob Dylan regularly visited him. Guthrie

died of complications of Huntington's disease on October 3, 1967. By

the time of his death, his work had been discovered by a new audience,

introduced to them in part through Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, his ex-wife Marjorie and other new members of the folk revival, and his son Arlo.