<Back to Index>

- Engineer Philippe Jean Bunau - Varilla, 1859

- Painter George Catlin, 1796

- Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I, 1678

PAGE SPONSOR

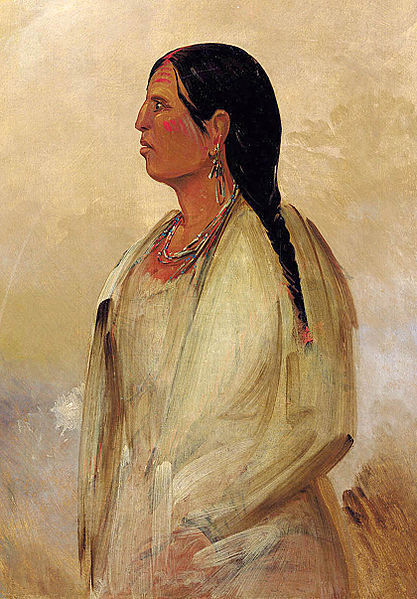

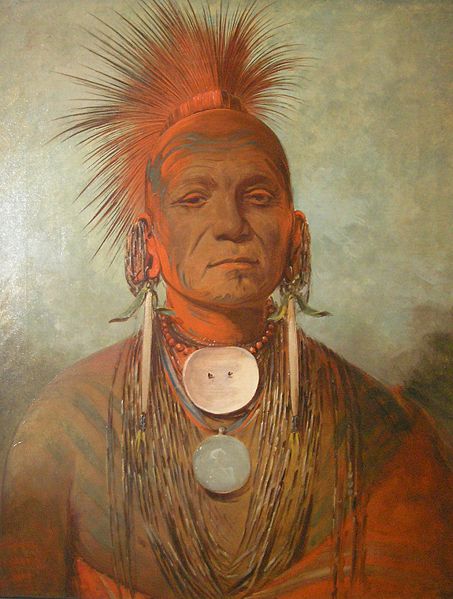

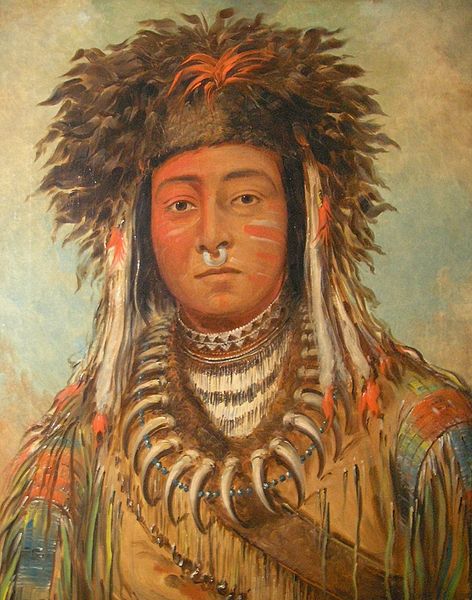

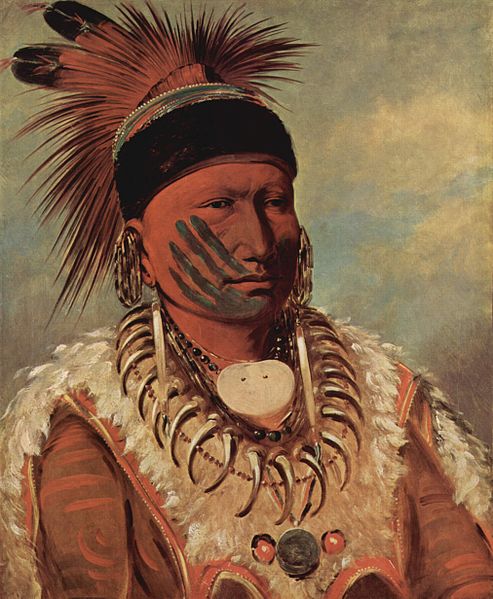

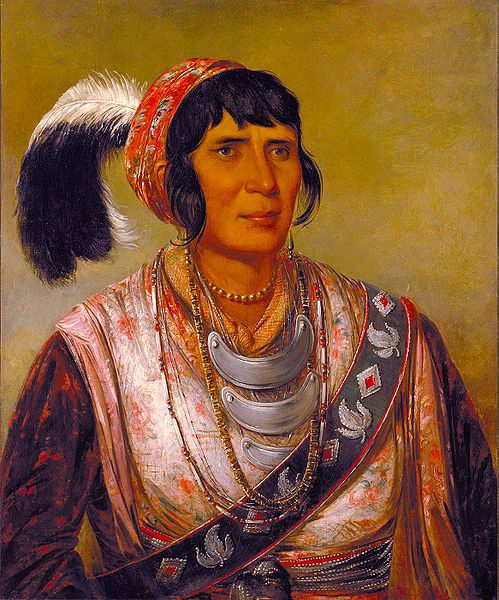

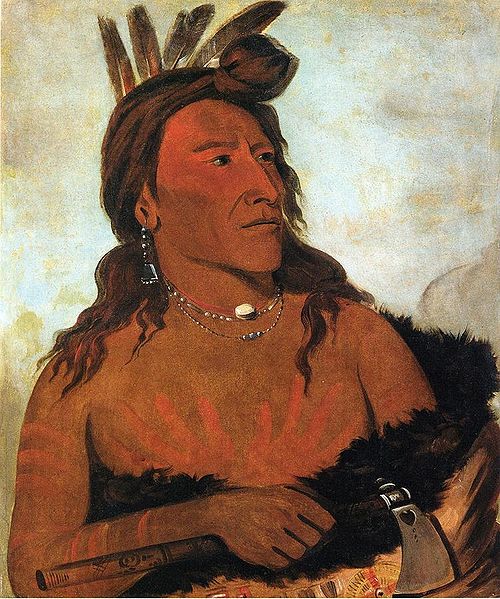

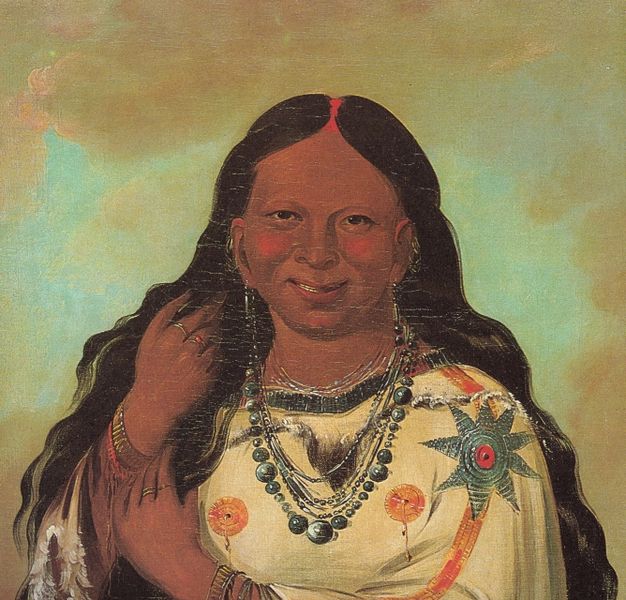

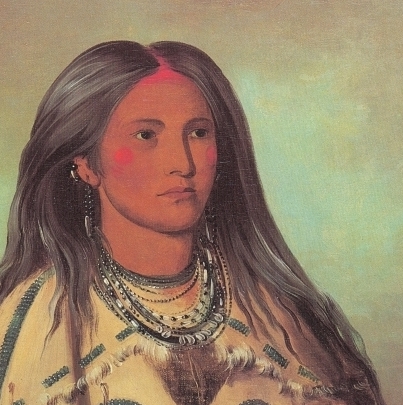

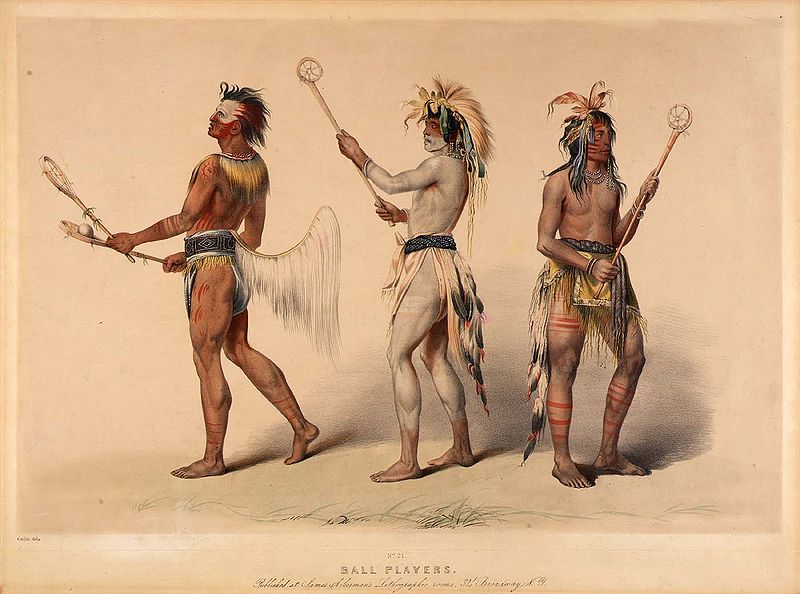

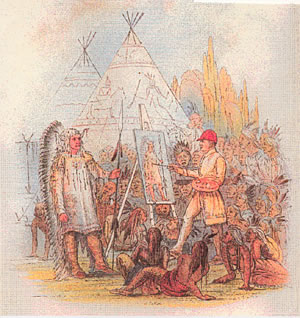

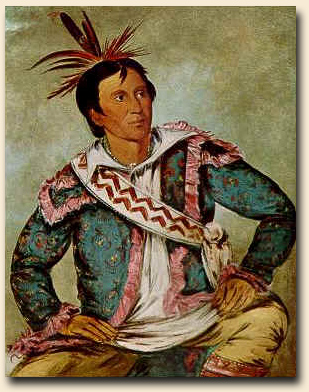

George Catlin (July 26, 1796 – December 23, 1872) was an American painter, author and traveler who specialized in portraits of Native Americans in the Old West.

Catlin was born in Wilkes - Barre, Pennsylvania. His early work included engravings drawn from nature of sites along the route of the Erie Canal in New York State. Several of his renderings were published in one of the first printed books to use lithography, Cadwallader D. Colden's Memoir, Prepared at the Request of a Committee of the Common Council of the City of New York, and Presented to the Mayor of the City, at the Celebration of the Completion of the New York Canals, published in 1825, with early images of the City of Buffalo.

As a child growing up in Pennsylvania, Catlin had spent many hours hunting, fishing, and looking for American Indian artifacts. His fascination with Native Americans was kindled by his mother, who told him stories of the Western Frontier and how she was captured by a tribe when she was a young girl. Years later, a group of Native Americans came through Philadelphia dressed in their colorful costumes and made quite an impression on Catlin. Following a brief career as a lawyer, he produced two major collections of paintings of American Indians and published a series of books chronicling his travels among the native peoples of North, Central and South America. Claiming his interest in America’s 'vanishing race' was sparked by a visiting American Indian delegation in Philadelphia, he set out to record the appearance and customs of America’s native people.

Catlin began his journey in 1830 when he accompanied General William Clark on a diplomatic mission up the Mississippi River into Native American territory. St. Louis became Catlin’s base of operations for five trips he took between 1830 and 1836, eventually visiting fifty tribes. Two years later he ascended the Missouri River over 3000 km to Fort Union Trading Post,

near what is now the North Dakota / Montana border, where he spent

several weeks among indigenous people who were still relatively

untouched by European civilization. He visited eighteen tribes, including the Pawnee, Omaha, and Ponca in the south and the Mandan, Hidatsa, Cheyenne, Crow, Assiniboine, and Blackfeet to

the north. There, at the edge of the frontier, he produced the most

vivid and penetrating portraits of his career. During later trips along the Arkansas, Red and Mississippi rivers, as well as visits to Florida and the Great Lakes, he produced more than 500 paintings and gathered a substantial collection of artifacts. When Catlin returned east in 1838, he assembled the paintings and numerous artifacts into his Indian Gallery,

and began delivering public lectures which drew on his personal

recollections of life among the American Indians. Catlin traveled with

his Indian Gallery to major cities such as Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and New York.

He hung his paintings “salon style” — side by side and one above

another — to great effect. Visitors identified each painting by the

number on the frame as listed in Catlin’s catalogue. Soon afterward he

began a lifelong effort to sell his collection to the U.S. government.

The touring Indian Gallery did not attract the paying public Catlin

needed to stay financially sound, and [Congress] rejected his initial

petition to purchase the works, so in 1839 Catlin took his collection

across the Atlantic for a tour of European capitals. Catlin the showman and entrepreneur initially attracted crowds to his Indian Gallery in London, Brussels, and Paris. The French critic Charles Baudelaire remarked

on Catlin’s paintings, “M. Catlin has captured the proud, free

character and noble expression of these splendid fellows in a masterly

way.” Catlin

wanted to sell his Indian Gallery to the U.S. government to have his

life’s work preserved intact. His continued attempts to persuade

various officials in Washington, D.C., failed.

In 1852 he was forced to sell the original Indian Gallery, now 607

paintings, due to personal debts. The industrialist Joseph Harrison

took possession of the paintings and artifacts, which he stored in a

factory in Philadelphia, as security. Catlin spent the last 20 years of

his life trying to re-create his collection. This second collection of

paintings is known as the "Cartoon Collection," since the works are

based on the outlines he drew of the works from the 1830s. In 1841 Catlin published Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, in two volumes, with about 300 engravings. Three years later he published 25 plates, entitled Catlin’s North American Indian Portfolio, and, in 1848, Eight Years’ Travels and Residence in Europe. From 1852 to 1857 he traveled through South and Central America and

later returned for further exploration in the Far West. The record of

these later years is contained in Last Rambles amongst the Indians of the Rocky Mountains and the Andes (1868) and My Life among the Indians (ed. by N.G. Humphreys, 1909). In 1872, Catlin traveled to Washington, D.C., at the invitation of Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian. Until his death later that year in Jersey City, New Jersey,

Catlin worked in a studio in the Smithsonian “Castle.” In 1879

Harrison’s widow donated the original Indian Gallery — more than 500

works — to the Smithsonian. The nearly complete surviving set of Catlin’s first Indian Gallery painted in the 1830s is now part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's collection. Some 700 sketches are in the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. The

accuracy of some of Catlin's observations has been questioned. He

claimed to be the first white man to see the Minnesota pipestone

quarries, and pipestone was named catlinite. Catlin exaggerated various

features of the site, and his boastful account of his visit aroused his

critics, who disputed his claim of being the first white man to

investigate the quarry. Previous recorded white visitors include the Groselliers and Radisson, Father Louis Hennepin, Baron LaHonton and others. Lewis and Clark noted the pipestone quarry in their journals in 1805. Fur trader Philander Prescott had written another account of the area in 1831.

Many historians and descendants believe George Catlin had two families; his acknowledged family on the east coast of the

United States, but also a family farther west, started with a Native American woman. Two other artists of the Old West related to George Catlin by family bloodlines are Frederic Remington and Earl W. Bascom.

Larry McMurtry includes Catlin as a character in his The Berrybender Narratives series of novels. In the historical novel The Children of First Man, James Alexander Thom recreates the time Catlin spent with the Mandan people. The 1970 film A Man Called Horse cites Catlin's work as one of the sources for its depiction of Lakota Sioux culture. Catlin and his work figure repeatedly in the 2010 novel Shadow Tag by Louise Erdrich, where he is the subject of the unfinished doctoral dissertation of character Irene America.