<Back to Index>

- Physicist Karl Ferdinand Braun, 1850

- Writer Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, 1799

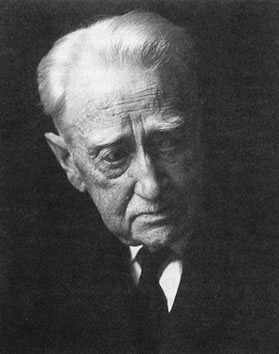

- 1st President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State William Thomas Cosgrave, 1880

PAGE SPONSOR

William Thomas Cosgrave (Irish: Liam Tomás Mac Cosgair; 6 June 1880 – 16 November 1965), known generally as W.T. Cosgrave, was an Irish politician who succeeded Michael Collins as Chairman of the Irish Provisional Government from August to December 1922. He served as the first President of the Executive Council (prime minister) of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1932.

William Thomas Cosgrave, W.T., or Liam as he was generally known, was born at 174 James's St, Dublin in 1880. He was educated at the Christian Brothers School at Malahide Road, Marino, before entering his father's publican business. Cosgrave first became politically active when he attended the first Sinn Féin convention in 1905.

He was a Sinn Féin councillor on Dublin Corporation from 1909 until 1922 and joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913. Cosgrave played an active role in the Easter Rising of 1916 serving under Eamonn Ceannt at the South Dublin Union. Following the rebellion Cosgrave was sentenced to death, however this was later commuted to penal servitude for life and he was interned in Frongoch, Wales. While in prison Cosgrave won a seat for Sinn Féin in the 1917 Kilkenny by-election.

He again won an Irish seat in the 1918 general election, serving as MP for Carlow – Kilkenny. He was released from prison in 1918 under a general amnesty and took part in the soon to be established Dáil Éireann. On 24 June 1919 Cosgrave married Louisa Flanagan in Dublin. Sinn

Féin proved to be the big winner of the election in Ireland,

capturing 73 Irish seats, 25 uncontested. Its manifesto promised abstentionism from the House of Commons in Westminster. On 21 January 1919, Sinn Féin's MPs who were not imprisoned assembled in the Round Room of the Mansion House in Dublin and formed themselves into an Assembly of Ireland, known in the Irish language as Dáil Éireann. Cathal Brugha became Príomh Aire (First or Prime Minister), also called President of Dáil Éireann. In April 1919 Brugha resigned and Éamon de Valera,

the Sinn Féin leader, who had just escaped from prison with the

help of Michael Collins using a key made from a candle, assumed the

premiership instead. The new government and state, known as the Irish Republic, claimed a right to govern the island of Ireland. It also declared UDI, that is, a declaration of independence which remained until the end of the Republic unrecognised by any other world state except the Russian Republic under Lenin. Though one of the most politically experienced of Sinn Féin's MPs (by now called Teachtaí Dála),

Cosgrave was not among the major leadership of the party. Nevertheless

he was appointed to de Valera's cabinet as Minister for Local

Government, his close friendship with de Valera being one of the

reasons he was chosen. Another reason was his long time experience

gained on Dublin Corporation, most recently as Chairman of its Finance

Committee. His chief task as minister was the job of organising the non-cooperation of the people with the British authorities

and establishing an alternative system of government. Cosgrave was very

successful in his role at the Department of Local Government. In 1920 he oversaw elections to local councils in which the new system of proportional representation was

used. Sinn Féin gained control of 28 of the 33 local councils.

These councils then cut their links to the British, and pledged loyalty

to the Sinn Féin Department of Local Government, under Cosgrave. Cosgrave broke with Éamon de Valera over the issue of the Anglo - Irish Treaty of

1921. To de Valera and almost half of the Sinn Féin TDs, the

treaty betrayed "the republic" by proposing to replace it with dominion

status akin to the position of Canada or Australia within the British Empire. To

a majority, however, republican status remained for the moment an

unattainable goal, with the republic unrecognised internationally. Dominion status offered, in the words of Michael Collins "the

freedom to achieve freedom." At the cabinet meeting in Dublin held to

consider the Treaty immediately after it had been signed, Cosgrave

surprised de Valera by agreeing with Collins and with Arthur Griffith,

de Valera's predecessor as leader of Sinn Féin and the chairman

of the delegation which included Collins that had negotiated the

Treaty. After the

Dáil voted by 64 to 57 to approve the Treaty in January, 1922,

De Valera resigned the presidency (which in August 1922 had been

upgraded from a prime ministerial President of Dáil

Éireann to a full head of state, called President of the Irish Republic).

De Valera was replaced as president by Griffith. Collins, in accordance

with the Treaty, formed a Provisional Government which included

Cosgrave. The

months following the acceptance of the Treaty saw a gradual progression

to civil war. The split in Sinn Féin gradually deepened and the

majority of the IRA hardened against accepting anything less than a

full republic. Collins and de Valera tried desperately to find a middle

course and formed a pact whereby Sinn Féin fought a General

Election in June with a common slate of candidates. Despite this pact,

the electorate voted heavily in favour of pro-Treaty parties. On the

day of the election, the draft Free State Constitution was published

and rejected by the Anti - Treatyites as it was clearly not a republican

document. Collins, forced to a decision, opted to maintain the Treaty

position and the support of the British Government, and moved to

suppress the Republican opposition that had seized the Four Courts in

Dublin. The Civil War started on 28 June 1922, and the IRA was

decisively defeated in the field over the following two months, being

largely pinned back to Munster.

In August 1922, both Griffith and Collins died in quick succession; the

former of natural causes, the latter a few days later when ambushed by

Republicans at Béal na mBláth. With de Valera now on the fringes as the leader of the Anti - Treaty forces in the Civil War,

the new dominion (which was in the process of being created but which

would not legally come into being until December 1922) had lost all its

most senior figures. Though it had the option of going for General Richard Mulcahy,

Collins' successor as Commander - in - Chief of the National Army, the

pro-Treaty leadership opted for Cosgrave, in part due to his democratic

credentials as a long time politician. Having previously held the Local

Government and Finance portfolios, he now became simultaneously

President of Dáil Éireann (Griffith had returned his

office to its pre-August 1922 name) and Chairman of the Provisional Government. When, on 6 December 1922, the Irish Free State came into being, Cosgrave became its first prime minister, called President of the Executive Council.

W.T.

Cosgrave was a small, quiet man, and at 42 was the oldest member of the

Cabinet. He had not sought the leadership of the new country but once

it was his he made good use of it. One of his chief priorities was to

hold the new country together and to prove that the Irish could govern

themselves. Some historians have noted that he lacked vision as a

leader and was surrounded by men who were more capable than himself.

However, over his ten years as President he provided the emerging Irish

state with an able leader who had a sound judgement on the matters of

state that the new country was facing. As

head of the Free State government during the Civil War, he was ruthless

in what he saw as defence of the state against his former republican

comrades. Although he actually disagreed with the use of the death penalty in

principle, in October 1922 he enacted a Public Safety Bill, which

allowed for the execution of anyone who was captured bearing arms

against the state or aiding armed attacks on state forces. He told the

Dáil on 27 September 1922, "although I have always objected to

the death penalty, there is no other way that I know of in which

ordered conditions can be restored in this country, or any security

obtained for our troops, or to give our troops any confidence in us as

a government". Cosgrave's position was that a guerrilla war could drag

on indefinitely, making the achievement of law and order and

establishing the Free State impossible, if harsh action was not taken.

His reputation suffered after he ordered the execution without trial of republican prisoners

during the civil war. In all 77 republicans were executed by the Free

State between November 1922 and the end of the war in May 1923,

including Robert Erskine Childers, Liam Mellowes and Rory O'Connor, far more than the 14 IRA Volunteers the British executed in the War of Independence.

The Republican side, for their part, attacked pro-Treaty politicians

and their homes and families. Cosgrave's family home was burned down by

Anti - Treaty fighters and an uncle of his was shot dead. Cosgrave said " I am not going to hesitate if the country is to live,

and if we have to exterminate ten thousand Republicans, the three

million of our people is greater than this ten thousand". In April 1923 the Pro-Treaty Sinn Féin members organised a new political party called Cumann na nGaedheal with

Cosgrave as leader. The following month the civil war was brought to an

end, when the remaining Anti - Treaty IRA guerrillas announced a

ceasefire and dumped their arms. In

the first few years in power Cosgrave's new government faced a number

of problems. Firstly, the government attempted to reduce the size of the Irish Army.

During the civil war it had grown to over 55,000 men which, now that

the civil war was over, was far too large and costly to maintain.

However, some army officers challenged the authority of the government

to cut the size of the Army. The officers, mostly Pro - Treaty IRA men,

were angry that the government was not doing enough to help to create a

republic and also that there would be massive unemployment. In March 1924 more layoffs were expected and the army officers, Major - General Liam Tobin and Colonel Charles Dalton sent an ultimatum to the government demanding an end to the demobilisation. Kevin O'Higgins,

the Minister for Justice, who was also acting President for Cosgrave

while the latter was in hospital, moved to resolve the so-called "Army

Mutiny". Richard Mulcahy,

the Minister for Defence, resigned and O'Higgins was victorious in a

very public power struggle within Cumann na nGaedheal. The crisis

within the army was solved but the government was divided. In 1924 the British and Irish governments agreed to attend the "Boundary Commission" to redraw the border which partitioned Ireland between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. The Free State's representative was Eoin MacNeill,

a respected scholar and Minister for Education. The Free State expected

to gain much territory in heavily Catholic and republican parts of

counties Londonderry, Fermanagh, Tyrone, and Armagh,

as the British government had indicated during the treaty negotiations

that the wishes of the nationalist inhabitants along the border would

be taken into account. However, after months of secret negotiations a

newspaper reported that there would be little change to the border and

the Free State would actually lose territory in Donegal.

MacNeill resigned from the commission and the government for not

reporting to Cosgrave on the details of the commission. Cosgrave

immediately went to London for a meeting with the British Prime Minister and the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland,

where they agreed to let the border remain as it was, and in return the

Free State did not have to pay its pro-rata share of the Imperial debt.

In the Dáil debate on 7 December Cosgrave stated: "I had only one figure in my mind and that was a huge nought. That was the figure I strove to get, and I got it." Cosgrave notably turned down a plea for asylum in Ireland for Leon Trotsky while in exile. The request was made by the trade union leader William X. O'Brien in 1930. Cosgrave told O'Brien Told

him [O'Brien] "I could see no reason why Trotsky should be considered

by us. Russian bonds had been practically confiscated. He said there

was to be consideration of them. I said it was not by Trotsky, whose

policy was the reverse. I asked his nationality. Reply Jew. They were

against religion (he said that was modified). I said not by Trotsky. He

said he had hoped there would be an asylum here as in England for all.

I agreed that under normal conditions, which we had not here, that

would be alright. But we had no touch with this man or his Government,

nor did they interest themselves in us in his 'day'. In

June, 1927, a general election was held in which de Valera's new party,

Fianna Fáil, won many seats on an abstentionist platform. In

July, the Minister for Justice, Kevin O'Higgins, was assassinated on

his way home from Sunday Mass by the IRA. Cosgrave had legislation

passed to force Fianna Fáil to take their seats in the

Dáil and this proved successful with de Valera and his party

entering the Dáil. Previously, without de Valera, Cosgrave faced

very little opposition, giving him considerable freedom of action.

However, de Valera's arrival significantly altered the situation. Although

Cosgrave and his government accepted dominion status for the Irish Free

State, they did not trust the British to respect this new independence.

The government embarked on fairly radical foreign initiatives. In 1923

the Irish Free State became a member of the League of Nations. The Free State became the first British Commonwealth country to have a separate or non-British representative in Washington, D.C.. The new state also exchanged diplomats with many other European nations. The Anglo - Irish Treaty itself also gave the Irish much more freedom than many other dominions. The Oath of Allegiance in Ireland was much less royalist than in Canada or Australia.

The king's representative in Ireland was Irish, unlike the other

dominions, and although the head of state was the king, power was

derived from the Irish people and not him. There were also questions

raised about the word "treaty". The British claimed it was an internal

affair while the Irish saw it as an international agreement between two

independent states, a point which was accepted by the League of

Nations, when that body registered the Treaty in 1924. During

the ten years that Cosgrave and Cumann na nGaedheal were in power they

adopted a conservative economic policy. Taxation was kept as low as

possible and the budget was balanced to avoid borrowing. The Irish

currency remained linked to the British currency, resulting in the

overvaluation of the Irish pound. Free trade was advocated as opposed

to protection, but moderate tariffs were introduced on some items. The

new government decided to concentrate on developing agriculture, while

doing little to help the industrial sector. Agriculture responded well

with stricter quality control being introduced and the passing of a

Land Act to help farmers buy their farms. Also, the Irish Sugar Company and the Agricultural Credit Corporation were

established to encourage growth. However, the economic depression that

hit in the 1930s soon undid the good work of Cosgrave and his

ministers. Industry was seen as secondary to agriculture and little was

done to improve it. The loss of the north-east of Ireland had a bad

effect on the country as a whole. However, the Electricity Supply Board, with the first national grid in Europe, was established to provide employment and electricity to the new state.

A

general election was not necessary until the end of 1932, however,

Cosgrave called one for February of that year. There was growing unrest

in the country and a fresh mandate was needed for an important

Commonwealth meeting in the summer. Another reason for calling the

election early was the pending Eucharistic Congress to be held in June.

This was a major national and international event. Cosgrave, as a

devout Catholic like most of his cabinet, had invested much time in the

build-up to it and wished it to procede without any tension fron a

pending General election. In the event Eamon de Valera and Fianna Fail

were the ones to derive all the kudos from that event. Cumann

na nGaedheal fought the election on its record of providing ten years

of honest government and political and economic stability. Instead of

developing new policies the party played the "red card" by portraying

the new party, Fianna Fáil,

as communists. Fianna Fáil offered the electorate a fresh and

popular manifesto of social reform. Unable to compete with this

Cosgrave and his party lost the election, and a minority Fianna

Fáil government came to power.

Following the general election Cosgrave assumed the nominal role of Leader of the Opposition.

Fianna Fáil were expected to have a short tenure in government,

however, this turned out to be a sixteen year period of rule by the new

party. In 1933 three groups, Cumann na nGaedheal, the National Centre Party and the National Guard came together to form a new political force, Fine Gael - the United Ireland Party.

Cosgrave became the first parliamentary leader of the new party,

serving until his retirement in 1944. During that period the new party

failed to win a general election. Cosgrave retired as leader of the

party and from politics in 1944. An

effective and good chairman rather than a colourful or charismatic

leader, he led the new state during the more turbulent period of its

history, when the legislation necessary for the foundation of a stable

independent Irish polity needed to be pushed through. Cosgrave's

governments in particular played a crucial role in the evolution of the British Empire into

the British Commonwealth, with fundamental changes to the concept of

the role of the Crown, the governor - generalship and the British

Government within the Commonwealth. In

overseeing the establishment of the formal institutions of the state

his performance as its first political leader may have been

undervalued. In an era when democratic governments formed in the

aftermath of the First World War were

moving away from democracy and towards dictatorships, the Free State

under Cosgrave remained unambiguously democratic, a fact shown by his

handing over of power to his one-time friend, then rival, Éamon

de Valera, when de Valera's Fianna Fáil won the 1932 general

election, in the process killing off talk within the Irish Army of

staging a coup to keep Cosgrave in power and de Valera out of it. Perhaps

the best endorsement made of Cosgrave came from his old rival, with

whom he was reconciled before his death, Éamon de Valera. De

Valera once in 1932 and later close to his own death, made two major

comments. To an interviewer, when asked what was his biggest mistake,

he said without a pause, "not accepting the Treaty". To his own son, Vivion,

weeks after taking power in 1932 and reading the files on the actions

of Cosgrave's governments in relation to its work in the Commonwealth,

he said of Cosgrave and Cosgrave's ministers ". . . when we got in and

saw the files. . . they did a magnificent job, Viv. They did a

magnificent job."

William T. Cosgrave died on 16 November 1965, aged 85. The Fianna Fáil government under

Seán Lemass awarded him the honour of a state funeral, which was attended by the cabinet, the leaders of all the main Irish political parties, and Éamon de Valera, then President of Ireland. He is buried in Goldenbridge Cemetery in Inchicore.

Richard Mulcahy said, "It is in terms of the Nation and its needs and

its potential that i praise God who gave us in our dangerous days the

gentle but steel-like spirit of rectitude, courage and humble self - sacrifice , that was Liam T. Cosgrave". Cosgrave's son, Liam, succeeded his father as a TD in 1944 and went on to become leader of Fine Gael from 1965 to 1977 and Taoiseach from 1973 to 1977. W.T.'s grandson, also called Liam also served as a TD and as Senator and his grand daughter Louise Cosgrave who served as a Dún Laoghaire - Rathdown County Councillor from 1999 to 2008.