<Back to Index>

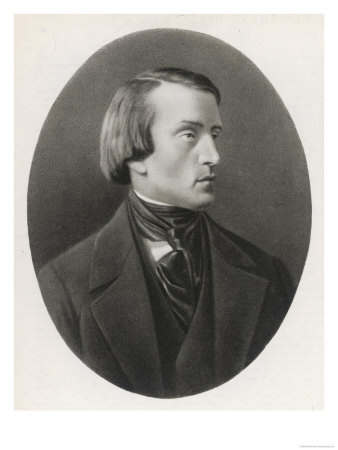

- Literary Critic Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky, 1811

- Photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, 1815

- Minister of the Interior Eduard Heinrich Rudolph David, 1863

PAGE SPONSOR

Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky (Russian: Виссарио́н Григо́рьевич Бели́нский) (June 11 [O.S. May 30] 1811 – June 7 [O.S. May 26] 1848) was a Russian literary critic of Westernizing tendency. He was an associate of Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin (he at one time courted one of his sisters), and other critical intellectuals. Belinsky played one of the key roles in the career of poet and publisher Nikolay Nekrasov and his popular magazine The Contemporary (also known as "Sovremennik").

Although born in Sveaborg, Helsinki, Vissarion Belinskii was based in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he was a respected critic and editor of two major literary magazines: Otechestvennye Zapiski ("Notes of the Fatherland"), and Sovremennik ("The Contemporary"). In both magazines Belinskii worked with younger Nikolay Nekrasov.

He was unlike most of the other Russian intellectuals of the 1830s and 1840s. The son of a rural medical doctor, he was not a wealthy aristocrat. The fact that Belinskii was relatively underprivileged meant, among other effects, that he was mainly self educated, unlike Alexander Herzen or Mikhail Bakunin, this was partly due to being expelled from Moscow University for political activity. But it was less for his philosophical skill that Belinskii was admired and more for emotional commitment and fervor. “For me, to think, to feel, to understand and to suffer are one and the same thing,” he liked to say. This was, of course, true to the Romantic ideal, to the belief that real understanding comes not only from mere thinking (reason), but also from intuitive insight. This combination of thinking and feeling pervaded Belinskii’s life.

Ideologically, Belinskii shared, but with exceptional intellectual and moral passion, the central value of most of Westernizer intelligentsia: the notion of the individual self, a person (lichnost), that which makes people human, and gives them dignity and rights. With this idea in hand (which he arrived at through a complex intellectual struggle) faced the world around him armed to do battle. He took on much conventional philosophical thinking among educated Russians, including the dry and abstract philosophizing of the German idealists and their Russian followers. In his words, “What is it to me that the Universal exists when the individual personality [lichnost] is suffering.” Or: “The fate of the individual, of the person, is more important than the fate of the whole world.” Also upon this principle, Belinskii constructed an extensive critique of the world around him (especially the Russian one). He bitterly criticized autocracy and serfdom (as “trampling upon everything that is even remotely human and noble”) but also poverty, prostitution, drunkenness, bureaucratic coldness, and cruelty toward the less powerful (including women).

Belinskii worked most of his short life as a literary critic. His writings on literature were inseparable from these moral judgments. Belinskii believed that the only realm of freedom in the repressive reign of Nicholas I was through the written word. What Belinskii required most of a work of literature was “truth.” This meant not only a probing portrayal of real life (he hated works of mere fantasy, or escape, or aestheticism), but also commitment to “true” ideas -- the correct moral stance (above all this meant a concern for the dignity of individual people): As he told Gogol (in a famous letter) the public “is always ready to forgive a writer for a bad book [i.e. aesthetically bad], but never for a pernicious one [ideologically and morally bad].” Belinskii viewed Gogol’s recent book, Correspondence with Friends, as pernicious because it renounced the need to “awaken in the people a sense of their human dignity, trampled down in the mud and the filth for so many centuries.”

In his role as perhaps the most influential liberal critic and ideologist of his day, Belinsky advocated literature that was socially conscious. He hailed Fyodor Dostoevsky's first novel, Poor Folk (1845), however, Dostoevsky soon thereafter broke with Belinsky.

Inspired by these ideas, which led to thinking about radical changes in society’s organization, Belinskii began to call himself a socialist starting in 1841. Among his last great efforts were his move to join Nikolay Nekrasov in the popular magazine The Contemporary (also known as "Sovremennik"), where the two critics established the new literary center of St. Petersburg and Russia. At that time Belinskii published his Literary Review for the Year 1847.

In 1848, shortly before his death, Belinskii granted full rights to Nikolay Nekrasov and his magazine, The Contemporary ("Sovremennik"), to publish various articles and other material originally planned for an almanac, to be called the Leviathan.

Belinskii died of consumption on the eve of his arrest by the Tsar's police on account of his political views. In 1910, Russia celebrated the centenary of his birth with enthusiasm and appreciation.

His surname has variously been spelled Belinsky or Byelinski. His works, in twelve volumes, were first published in 1859 – 1862. Following the expiration of the copyright in 1898, several new editions appeared. The best of these is by S. Vengerov; it is supplied with profuse notes.

Belinskii was an early supporter of the work of Ivan Turgenev. The two became close friends and Turgenev fondly recalls Belinskii in his book Literary Reminiscences and Autobiographical Fragments. The British writer Isaiah Berlin has a chapter on Belinskii on his 1978 book Russian Thinkers. Here he points out some deficiencies of Belinsky's critical insight:

He was wildly erratic, and all his enthusiasm and seriousness and integrity do not make up for lapses of insight or intellectual power. He declared that Dante was not a poet; that Fenimore Cooper was the equal of Shakespeare; that Othello was the product of a barbarous age...

But further on in the same essay, Berlin remarks:

Because he was naturally responsive to everything that was living and genuine, he transformed the concept of the critic's calling in his native country. The lasting effect of his work was in altering and altering crucially and irretrievably, the moral and social outlook of the leading younger writers and thinkers of his time. He altered the quality and the tone both of the experience and of the expression of so much Russian thought and feeling that his role as a dominant social influence overshadows his attainments as a literary critic.

Berlin's book introduced Belinskii to playwright Tom Stoppard, who included Belinskii as one of the principal characters (along with Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin and Turgenev) in his trilogy of plays about Russian writers and activists: The Coast of Utopia (2002).