<Back to Index>

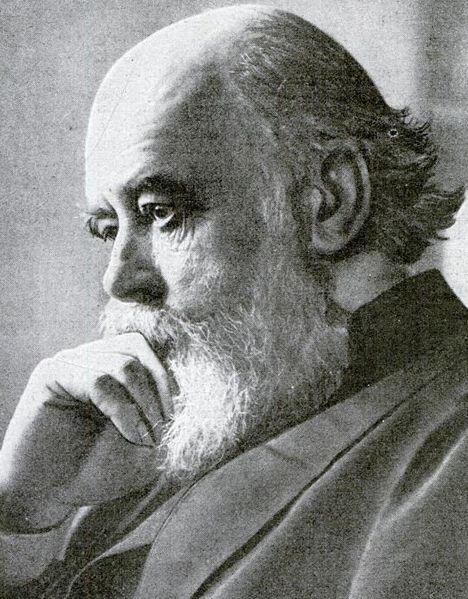

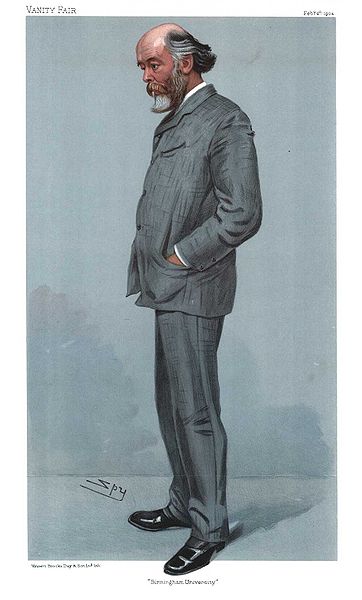

- Physicist Oliver Joseph Lodge, 1851

- Writer Djuna Barnes, 1892

- Song Emperor of China Gaozong, 1107

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge, FRS (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was a British physicist and writer involved in the development of key patents in wireless telegraphy. In his 1894 Royal Institution lectures ("The Work of Hertz and Some of His Successors"), Lodge coined the term "coherer" for the device invented by the Italian physicist Temistocle Calzecchi Onesti. In 1898 he was awarded the "syntonic" (or tuning) patent by the United States Patent Office. He was also credited by Lorentz (1895) with the first published description of the length contraction hypothesis, in 1893, though in fact Lodge's friend George Francis FitzGerald had first suggested the idea in print in 1889.

Oliver Lodge was born in 1851 at Penkhull in Stoke-on-Trent and educated at Adams' Grammar School. He was the eldest of eight sons and a daughter of Oliver Lodge (1826 – 1884) - later a ball clay merchant at Wolstanton, Staffordshire - and his wife, Grace, née Heath (1826 – 1879). Sir Oliver's siblings included Sir Richard Lodge (1855 – 1936), historian; Eleanor Constance Lodge (1869 – 1936), historian and principal of Westfield College, London; and Alfred Lodge (1854 – 1937), mathematician.

In 1865, Lodge, at the age of 14, entered his father's business (Oliver Lodge & Son) as an agent for B. Fayle & Co selling Purbeck blue clay to the potteries, travelling as far as Scotland. He continued to assist his father until he reached the age of 22. His father's wealth obtained from selling Purbeck ball clay enabled Lodge to attend physics lectures in London and attend the local Wedgwood Institute.

Lodge obtained a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of London in 1875 and a Doctor of Science in 1877. He was appointed professor of physics and mathematics at University College, Liverpool, in 1881. In 1900 Lodge moved from Liverpool back to the Midlands and became the first principal of the new Birmingham University, remaining there until his retirement in 1919. He oversaw the start of the move of the university from Edmund Street in the city centre to its present Edgbaston campus. Lodge was awarded the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society in 1898 and was knighted by King Edward VII in 1902. In 1928 he was made Freeman of his native city, Stoke - on - Trent.

Lodge married Mary Fanny Alexander Marshall at St George's church, Newcastle - under - Lyme in 1877. They had twelve children, six boys and six girls. Four of his sons went into business using Lodge's inventions. Brodie and Alec created the Lodge Plug Company, which manufactured sparking plugs for cars and aeroplanes. Lionel and Noel founded a company that produced an electrostatic device for cleaning factory and smelter smoke in 1913, called the Lodge Fume Deposit Company Limited (changed in 1919 to Lodge Fume Company Limited and in 1922, through agreement with the International Precipitation Corporation of California, to Lodge Cottrell Ltd). Oliver, the eldest son, became a poet and author.

After his retirement in 1920, Sir Oliver and Lady Lodge settled in Normanton House, near Lake in Wiltshire, just a few miles from Stonehenge. Lodge and his wife are buried at St. Michael’s Church, Wilsford (Lake), Wiltshire. Their eldest son Oliver and eldest daughter Violet are buried at the same church. Maxwell's "Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism"

appeared in 1873 and by 1876 Lodge was studying it intently. But he was

fairly limited in mathematical physics both by aptitude and training

and his first two papers were a description of a mechanism (of beaded

strings and pulleys) that could serve to illustrate electrical

phenomena such as conduction and polarization. Indeed, Lodge is

probably best known for his advocacy and elaboration of Maxwell's aether theory

- a later deprecated model postulating a wave - bearing medium filling

all space. He explained his views on the aether in "Modern Views of Electricity" (1889) and continued to defend those ideas well into the twentieth century ("Ether and Reality", 1925). As

early as 1879 Lodge became interested in generating (and detecting)

electromagnetic waves, something Maxwell had never considered. This

interest continued throughout the 1880s but three obstacles slowed

Lodge's progress. First, he thought in terms of generating light waves

with their very high frequencies rather than radio waves with their

much lower frequencies. Second, his good friend George FitzGerald (on

whom Lodge depended for theoretical guidance) assured him (incorrectly)

that "ether waves could not be generated electromagnetically." FitzGerald

later corrected his error but by 1881 Lodge had assumed a teaching

position at University College, Liverpool, the demands of which limited

his time and his energy for research. And so it was Heinrich Hertz in Germany who was the first to demonstrate the transmission of electromagnetic waves in 1888. On 14 August 1894, at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science at

Oxford University, Lodge gave a lecture on the work of Hertz (recently

deceased) and transmitted radio signals to demonstrate their potential

for communication. This was one year before Marconi but one year after Tesla did

the same thing. On June 25, 1995, the Royal Society recognized this

scientific achievement at a special ceremony at Oxford University. Lodge improved Edouard Branly's

coherer radio wave detector by adding a "trembler" which dislodged

clumped filings, thus restoring the device's sensitivity. He worked with Alexander Muirhead on the development of wireless telegraphy, selling their patents to Marconi in 1912. Lodge also carried out scientific investigations on lightning, the source of the electromotive force in the voltaic cell, electrolysis, and the application of electricity to the dispersal of fog and smoke. Lodge also made a major contribution to motoring when he patented a form of electric spark ignition for the internal combustion engine (the Lodge Igniter). Later, two of his sons developed his ideas and in 1903 founded Lodge Bros, which eventually became known as Lodge Plugs Ltd. He also made discoveries in the field of wireless transmission. In 1898, Lodge gained a patent on the moving - coil loudspeaker, utilizing a coil connected to a diaphragm, suspended in a strong magnetic field. His "syntonic" tuner patent allowed

the frequency of transmitter and receiver to be "verified with ease and

certainty". This was a basic patent in the industry, unusually

recognized as such when extended, and purchased and used by the Marconi

Company. In political life, Lodge was an active member of the Fabian Society and

published two Fabian Tracts: Socialism & Individualism (1905) and co-authored Public Service versus Private Expenditure with Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Ball. They invited him several times to lecture at the London School of Economics. Lodge is also remembered for his studies of life after death. He first began to study psychical phenomena (chiefly telepathy) in the late 1880s, was a member of the Ghost Club and served as president of the London based Society for Psychical Research from 1901 to 1903. After his son, Raymond, was killed in World War I in

1915, Lodge visited several mediums and wrote about the experience in a

number of books, including the best selling "Raymond, or Life and

Death" (1916). The parallel with fellow Ghost Club member Arthur Conan Doyle,

who also lost a son in World War I and turned to spiritualism is

striking. Altogether, Lodge wrote more than 40 books, about the afterlife, aether, relativity, and electromagnetic theory. In 1889 Lodge was appointed President of the Liverpool Physical Society, a position he held until 1893. The society still runs to this day, though under a student body. The author of his obituary in The Times wrote: Always

an impressive figure, tall and slender with a pleasing voice and

charming manner, he enjoyed the affection and respect of a very large

circle… Lodge’s

gifts as an expounder of knowledge were of a high order, and few

scientific men have been able to set forth abstruse facts in a more

lucid or engaging form… Those who heard him on a great occasion, as

when he gave his Romanes lecture at Oxford or his British Association presidential

address at Birmingham, were charmed by his alluring personality as well

as impressed by the orderly development of his thesis.

But he was even better in informal debate, and when he rose, the

audience, however perplexed or jaded, settled down in a pleased

expectation that was never disappointed. Oliver Lodge Primary School in Vanderbijlpark, South Africa is named in his honour.