<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Grigori Yakovlevich Perelman, 1966

- Poet Fernando António Nogueira de Seabra Pessoa, 1888

- Proconsul of the Roman Empire Gnaeus Julius Agricola, 40

PAGE SPONSOR

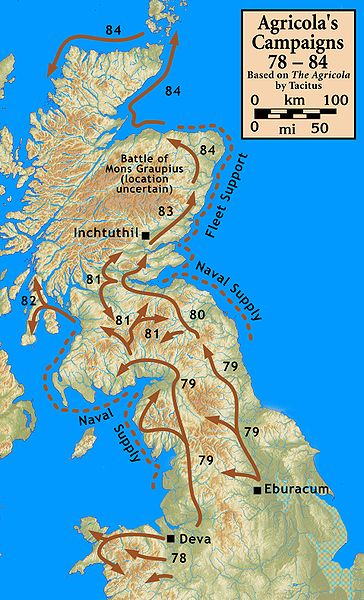

Gnaeus Julius Agricola (June 13, 40 – August 23, 93) was a Roman general responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. His biography, the De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae, was the first published work of his son-in-law, the historian Tacitus, and is the source for most of what is known about him.

Born to a noted political family, Agricola began his military career in Britain, serving under governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. His subsequent career saw him serve in a variety of positions; he was appointed quaestor in Asia province in 64, then Plebeian Tribune in 66, and praetor in 68. He supported Vespasian during the Year of the Four Emperors (69), and was given a military command in Britain when the latter became emperor. When his command ended in 73 he was made patrician in Rome and appointed governor of Gallia Aquitania. He was made consul and governor of Britannia in 77. While there, he conquered much of what is now Wales and northern England, and ventured into lowland Scotland, where he established Roman dominance for a time. Some speculate that he may have launched an expedition into Ireland as

well. He was recalled from Britain in 85 after an unusually lengthy

service, and thereafter retired from military and public life. Agricola was born in the colonia of Forum Julii, Gallia Narbonensis (modern southern France). Agricola's parents were from families of senatorial rank. Both of his grandfathers served as Imperial Governors. His father Julius Graecinus was a praetor and had become a member of the Roman Senate in the year of his birth. Graecinus had become distinguished by his interest in philosophy. Between August 40 - January 41, the Roman Emperor Caligula ordered his death because he refused to prosecute the Emperor's second cousin Marcus Silanus. His mother was Julia Procilla. The Roman historian Tacitus describes

her as "a lady of singular virtue". Tacitus states that Procilla had a

fond affection for her son. Agricola was educated in Massilia (Marseille), and showed what was considered an unhealthy interest in philosophy. He began his career in Roman public life as a military tribune, serving in Britain under Gaius Suetonius Paulinus from 58 to 62. He was probably attached to the Legio II Augusta, but was chosen to serve on Suetonius's staff and thus almost certainly participated in the suppression of Boudica's uprising in 61. Returning from Britain to Rome in 62, he married Domitia Decidiana, a woman of noble birth. Their first child was a son. Agricola was appointed to the quaestorship for 64, which he served in the province of Asia under the corrupt proconsul Salvius Titianus. While he was there his daughter, Julia Agricola, was born, but his son died shortly afterwards. He was tribune of the plebs in 66 and praetor in 68, during which time he was ordered by Galba to take an inventory of the temple treasures. In June of 68 the emperor Nero was deposed and committed suicide, and the period of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors began. Galba succeeded Nero, but was murdered in early 69 by Otho, who took the throne. Agricola's mother was murdered on her estate in Liguria by Otho's marauding fleet. Hearing of Vespasian's bid for the empire, Agricola immediately gave him his support. After Vespasian had established himself as emperor, Agricola was appointed to the command of the Legio XX Valeria Victrix, stationed in Britain, in place of Marcus Roscius Coelius, who had stirred up a mutiny against the governor, Marcus Vettius Bolanus. Britain had suffered revolt during the year of civil war, and Bolanus

was a mild governor. Agricola reimposed discipline on the legion and

helped to consolidate Roman rule. In 71 Bolanus was replaced by a more

aggressive governor, Quintus Petillius Cerialis, and Agricola was able to display his talents as a commander in campaigns against the Brigantes. When his command ended in 75, Agricola was enrolled as a patrician and appointed to govern Gallia Aquitania. In 76 or 77 he was recalled to Rome and appointed suffect consul, and betrothed his daughter to Tacitus. The following year Tacitus and Julia married; Agricola was appointed to the College of Pontiffs, and returned to Britain for a third time, as its governor. Arriving in mid-summer of 77, Agricola found that the Ordovices of

north Wales had virtually destroyed the Roman cavalry stationed in

their territory. He immediately moved against them and defeated them.

He then moved north to the island of Mona (Anglesey), which had previously been reduced by Suetonius Paulinus in 61 but must

have been regained by the Britons in the meantime, and forced its

inhabitants to sue for peace. He established a good reputation as an

administrator as well as a commander by reforming the widely corrupt

corn levy. He introduced Romanising measures, encouraging communities

to build towns on the Roman model and educating the sons of the native

nobility in the Roman manner. He also expanded Roman rule north into Caledonia (modern Scotland).

In the summer of 79 he pushed his armies to the estuary of the river

Taus, virtually unchallenged, and established forts there. This is

often interpreted as the Firth of Tay, but this would appear to be anomalous as it is further north than the Firths of Clyde and Forth, which Agricola did not reach until the following year. Others suggest the Taus was the Solway Firth. Irish legend provides a striking parallel. Tuathal Teachtmhar, a legendary High King,

is said to have been exiled from Ireland as a boy, and to have returned

from Britain at the head of an army to claim the throne. The

traditional date of his return is 76 - 80, and archaeology has found Roman or Romano - British artefacts in several sites associated with Tuathal.

The following year Agricola raised a fleet and encircled the tribes beyond the Forth, and the

Caledonians rose in great numbers against him. They attacked the camp of the Legio IX Hispana at night,

but Agricola sent in his cavalry and they were put to flight. The

Romans responded by pushing further north. Another son was born to

Agricola this year, but he died before his first birthday. In the summer of 83 Agricola faced the massed armies of the Caledonians, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Tacitus estimates their numbers at more than 30,000. Agricola

put his auxiliaries in the front line, keeping the legions in reserve,

and relied on close quarters fighting to make the Caledonians'

unpointed slashing swords useless. Even though the Caledonians were put

to rout and therefore lost this battle, two thirds of their army

managed to escape and hide in the Scottish Highlands or the "trackless

wilds" as Tacitus calls them. Battle casualties were estimated by

Tacitus to be about 10,000 on the Caledonian side and 360 on the Roman

side. A number of authors have reckoned the battle to have occurred in the Grampian Mounth within sight of the North Sea. In particular, Roy, Surenne, Watt, Hogan and others have advanced notions that the site of the battle may have been Kempstone Hill, Megray Hill or other knolls near the Raedykes Roman Camp. In addition these points of high ground are proximate to the Elsick Mounth, an ancient trackway used by Romans and Caledonians for military maneuvers. Satisfied

with his victory, Agricola extracted hostages from the Caledonian

tribes. He may have marched his army to the northern coast of Britain, as evidenced by the probable discovery of a Roman fort at Cawdor (near Inverness). He also instructed the prefect of the fleet to sail around the north coast, confirming for the first time that Britain was in fact an island.

Agricola was recalled from Britain in 85, after an unusually long tenure as governor. Tacitus claims that Domitian ordered

his recall because Agricola's successes outshone the Emperor's own

modest victories in Germany. The relationship between Agricola and the

Emperor is unclear: on the one hand, Agricola was awarded triumphal

decorations and a statue (the highest military honours apart from an

actual triumph);

on the other, Agricola never again held a civil or military post, in

spite of his experience and renown. He was offered the governorship of

the province of Africa, but declined it, whether due to ill health or

(as Tacitus claims) the machinations of Domitian. In 93 Agricola died

on his family estates in Gallia Narbonensis aged fifty-three.

In 81 Agricola "crossed in the first ship" and defeated peoples unknown to the Romans until then. Tacitus, in Chapter 24 of

Agricola, does

not tell us what body of water he crossed, although most scholars

believe it was the Clyde or Forth, and some translators even add the

name of their preferred river to the text; however, the rest of the

chapter exclusively concerns Ireland. The text of the Agricola has been emended here to record the Romans "crossing into trackless wastes", referring to the wilds of the Galloway peninsula. Agricola

fortified the coast facing Ireland, and Tacitus recalls that his

father-in-law often claimed the island could be conquered with a single legion and auxiliaries.

He had given refuge to an exiled Irish king whom he hoped he might use

as the excuse for conquest. This conquest never happened, but some

historians believe that the crossing referred to was in fact a

small scale exploratory or punitive expedition to Ireland.