<Back to Index>

- Biochemist Ernst Boris Chain, 1906

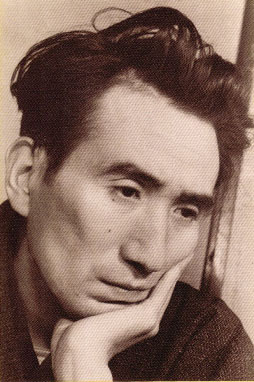

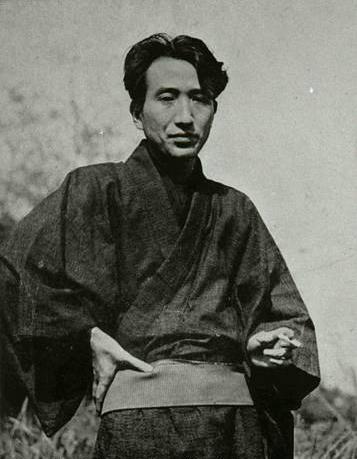

- Writer Osamu Dazai, 1909

- President of the Swiss Federal Council Enrico Celio, 1889

PAGE SPONSOR

Osamu Dazai (太宰 治 Dazai Osamu, June 19, 1909 – June 13, 1948) was a Japanese author who is considered one of the foremost fiction writers of 20th century Japan. He is noted for his ironic and gloomy wit, his obsession with suicide, and his brilliant fantasy.

| “ | The year before last I was expelled from my family and, reduced to poverty overnight, was left to wander the streets, begging help from various quarters, barely managing to stay alive from one day to the next, and just when I'd begun to think I might be able to support myself with my writing, I came down with a serious illness. Thanks to the compassion of others, I was able to rent a small house in Funabashi, Chiba, next to the muddy sea, and spent the summer there alone, convalescing. Though battling an illness that each and every night left my robe literally drenched with sweat, I had no choice but to press ahead with my work. The cold half pint of milk I drank each morning was the only thing that gave me a certain peculiar sense of the joy in life; my mental anguish and exhaustion were such that the oleanders blooming in one corner of the garden appeared to me merely flicking tongues of flame... | ” |

—Seascape with Figures in Gold (1939), Osamu Dazai | ||

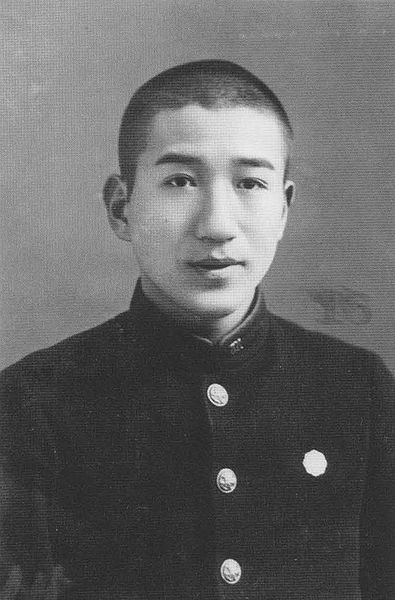

Tsushima was sent to Aomori Prefectural Aomori High School and Hirosaki for higher school. An excellent student and an able writer even then, he edited student publications and contributed some of his own works. His life only started to change when his idol writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa committed suicide in 1927. Tsushima started to neglect his studies, spending his allowance on clothes, alcohol and prostitutes and dabbling with Marxism, at the time heavily suppressed by the government. He frequently expressed guilt in his earliest writing about having been born into what he thought of as the incorrect social class. On 10 December 1929, the night before year - end exams that he had no hopes of passing, Tsushima attempted to commit suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping pills, but he survived and managed to graduate the following year.

Tsushima enrolled in the French Literature Department of the Tokyo Imperial University and promptly stopped studying again. In October, he ran away with geisha Hatsuyo Oyama (小山初代 Oyama Hatsuyo) and was formally expelled from his family. Nine days after the expulsion, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in Kamakura with another woman (whom he barely knew), 19 year old bar hostess Shimeko Tanabe (田辺シメ子 Tanabe Shimeko). Shimeko died, but Tsushima lived, having been rescued by a fishing boat, leaving him with a strong sense of guilt. Shocked by the events, Tsushima's family intervened to drop a police investigation, his allowance was reinstated and in December Tsushima and Oyama were married.

This moderately happy state of affairs did not last long, as Tsushima was arrested for his involvement with the banned Communist Party of Japan and,

upon learning this, his elder brother Bunji promptly cut off his

allowance again. Tsushima went into hiding, but Bunji managed to get

word to him that charges would be dropped and the allowance reinstated

yet again if he solemnly promised to graduate and swear off any

involvement with the party, and Tsushima took up the offer.

In what was probably a surprise to all parties concerned, Tsushima kept his promise and managed to settle down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer Masuji Ibuse, whose connections enabled him to get his works published, and who helped establish his reputation.

The next few years were productive, Tsushima wrote at a feverish pace and used the pen name "Osamu Dazai" for the first time in a short story called Ressha (列車 Train 1933): his first experiment with the first person autobiographical style that later became his trademark. But in 1935, it started to become clear that Dazai could not graduate, and he failed to obtain a job at a Tokyo newspaper as well. He finished The Final Years, intended to be his farewell to the world, and tried to hang himself on 19 March 1935 - failing yet again.

Worse was yet to come, as less than three weeks after his third suicide attempt Dazai developed acute appendicitis and was hospitalized, during which time he became addicted to Pabinal, a morphine based painkiller. After fighting the addiction for a year, in October 1936 he was taken to a mental institution, locked in a room and forced to quit cold turkey. The "treatment" lasted over a month, during which time Dazai's wife Hatsuyo committed adultery with his best friend Zenshirō Kodate. This eventually came to light and Dazai attempted to commit double suicide with his wife. They both took sleeping pills, but neither one died, so he divorced her. He quickly remarried, this time to a middle school teacher named Michiko Ishihara (石原美知子 Ishihara Michiko). Their first daughter, Sonoko (園子), was born in June 1941.

In

the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short

stories that are frequently autobiographical in nature. His first story, Gyofukuki (魚服記 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include Dōke no hana (The Flowers of Buffoonery, 1935), Gyakkō (逆行 Against the Current, 1935), Kyōgen no kami (狂言の神 The God of Farce, 1936), and those published in his 1936 collection Bannen (Declining Years), which describe his sense of personal isolation and his debauchery.

Japan entered the Pacific War in December, but Dazai was excused from the draft because of his chronic chest problems (he was diagnosed with tuberculosis). The censors became more reluctant to accept Dazai's offbeat work, but he managed to publish quite a bit anyway, remaining one of the very few authors who managed to turn out interesting material in those years. A number of the stories, which Dazai published during World War II were retellings of stories by Ihara Saikaku (1642 - 1693). Wartime works included Udaijin Sanetomo (Minister of the Right Sanetomo, 1943), Tsugaru (1944), Pandora no hako (Pandora's Box, 1945 - 46), and the delightful Otogizōshi (Fairy Tales, 1945) in which he retold a number of old Japanese fairy tales with vividness and wit.

His house was burned down twice in the American air raids against Tokyo,

but Dazai's family escaped unscathed, with a son, Masaki (正樹), born in

1944. His third child, daughter Satoko (里子), later became a famous

writer under the pseudonym Yūko Tsushima (津島佑子), was born in May 1947.

In the immediate post-war period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity.

He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in Viyon no Tsuma (Villon's Wife, 1947). The narrator is the wife of a poet, who has abandoned her. She takes a job for a tavern keeper from whom her husband has stolen money. Her determination to survive is tested by hardships, rape and her husband's self - delusion, but her will is not broken.

In July 1947 Dazai's best known work, Shayo (The Setting Sun, translated 1956) depicting the decline of the Japanese nobility after World War II was published, propelling the already popular writer into a celebrity. This work was based on the diary of Shizuko Ōta (太田静子). Ōta was one of the fans of Dazai's works and first met him in about 1941. She bore him a daughter Haruko (治子) in 1947.

Always a heavy drinker, he became an alcoholic; he had already fathered a child out of wedlock with a fan, and his health was also rapidly deteriorating. At this time Dazai met Tomie Yamazaki (山崎富栄), a beautician and war widow who had lost her husband after 10 days of married life. Dazai effectively abandoned his wife and children and moved in with Tomie, writing his quasi - autobiography Ningen Shikkaku (人間失格, No Longer Human, 1948, translated. 1958) at the hot-spring resort Atami.

Ningen Shikkaku deals

with a character hurtling headlong towards self - destruction, all the

while despairing of the seeming impossibility of changing the course of

his life. The novel is told in a brutally honest manner, devoid of all

sentimentality. The book is one of the classics of Japanese literature and has been translated into several foreign languages.

In the spring of 1948, he was working on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, titled Guddo bai (Goodbye). On 13 June 1948, Dazai and Tomie finally succeeded in killing themselves, drowning in the rain - swollen Tamagawa Canal near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until June 19, which by eerie coincidence was his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in Mitaka, Tokyo.

There

has been a persistent rumor that his final, successful suicide attempt

was not a suicide at all, but that he was murdered by Tomie Yamazaki,

who then killed herself after dumping his body in the canal. While

providing a plot for various subsequent fictional novels and a Japanese

TV drama, there has been no proof that there is any veracity in this

rumor.

The single most distinguishing feature of Dazai's works is their “first person” viewpoint, a style known in Japanese as "I Novels (私小説 Shishōsetsu)". All of his stories are autobiographical in some manner. His modes of expression could take the form of a diary, essay, letter, journalistic type reporting, or soliloquy.

Dazai's works are also characterized by a profound pessimism, not surprising from an author who made several unsuccessful suicide attempts before finally succeeding. In his novels the protagonist similarly consider suicide as the only viable alternative to a hellish existence, yet (often) fail to kill themselves due to an equally savage apathy towards their own existence i.e. the question of whether to live or not becomes trivial. In his works, he shifts from pathos to comedy, from melodrama to humor, adjusting his vocabulary accordingly.

His opposition to the prevailing social and literary trends was shared by fellow members of the Buraiha school, including Ango Sakaguchi and Sakunosuke Oda.