<Back to Index>

- Astronomer John Frederick William Herschel, 1792

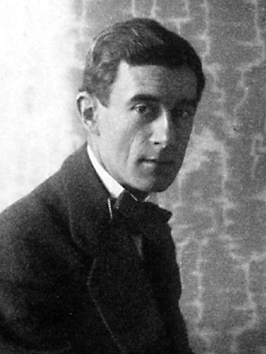

- Composer Joseph Maurice Ravel, 1875

- Prince of the Palatinate - Simmern Johann Casimir, 1543

PAGE SPONSOR

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (March 7, 1875 – December 28, 1937) was a French composer known especially for his melodies, orchestral and instrumental textures and effects. Much of his piano music, chamber music, vocal music and orchestral music has entered the standard concert repertoire.

Ravel's piano compositions, such as Jeux d'eau, Miroirs, Le tombeau de Couperin and Gaspard de la nuit, demand considerable virtuosity from the performer, and his orchestral music, including Daphnis et Chloé and his arrangement of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, uses a variety of sound and instrumentation. Ravel is perhaps known best for his orchestral work Boléro (1928), which he considered trivial and once described as "a piece for orchestra without music." According to SACEM, Ravel's estate earns more royalties than that of any other French composer. According to international copyright law, Ravel's works have been in the public domain since January 1, 2008, in most countries. In France, due to anomalous copyright law extensions to account for the two world wars, they will not enter the public domain until 2015.

Ravel was born in the Basque town of Ciboure, France, near Biarritz, close to the border with Spain, in 1875. His mother, Marie Delouart, was of Basque descent and grew up in Madrid, Spain, while his father, Joseph Ravel, was a Swiss inventor and industrialist from French Haute - Savoie. Both were Catholics and they provided a happy and stimulating household for their children. Some of Joseph's inventions were quite important, including an early internal combustion engine and a notorious circus machine, the "Whirlwind of Death," an automotive loop - the - loop that was quite a success until a fatal accident at the Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1903. Joseph delighted in taking his sons to factories to see the latest mechanical devices, and he also had a keen interest in music and culture. Ravel substantiated his father's early influence by stating later, “As a child, I was sensitive to music —- to every kind of music.”

Ravel was very fond of his mother, and her Basque heritage was a strong influence on his life and music. Among his earliest memories are folk songs she sang to him. The family moved to Paris three months after the birth of Maurice, and there his younger brother Édouard was born. Édouard became his father’s favorite and also became an engineer. At age six, Maurice began piano lessons with Henry Ghys and received his first instruction in harmony, counterpoint, and composition with Charles - René. His earliest public piano recital was during 1889 at age fourteen.

Though obviously talented at the piano, Ravel demonstrated a preference for composing. He was particularly impressed by the new Russian works conducted by Nikolai Rimsky - Korsakov at the Exposition Universelle in 1889. The foreign music at the exhibition also had a great influence on Ravel’s contemporaries Erik Satie, Emmanuel Chabrier, and most significantly Claude Debussy. That year Ravel also met Ricardo Viñes, who would become one of his best friends, one of the foremost interpreters of his piano music, and an important link between Ravel and Spanish music. The students shared an appreciation for Richard Wagner, the Russian school, and the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Stéphane Mallarmé.

Ravel’s parents encouraged his musical pursuits and sent him to the Conservatoire de Paris, first as a preparatory student and eventually as a piano major. His teachers included Émile Descombes. He received a first prize in the piano student competition in 1891. Overall, however, he was not successful academically even as his musicianship matured dramatically. Considered “very gifted”, Ravel was also called “somewhat heedless” in his studies. Around 1893, Ravel created his earliest compositions, and he was introduced by his father to the café pianist Erik Satie, whose distinctive personality and unorthodox musical experiments proved influential.

Ravel was not a "bohemian" and evidenced little of the typical trauma of adolescence. At twenty years of age, Ravel was already "self - possessed, a little aloof, intellectually biased, given to mild banter." He dressed like a dandy and was meticulous about his appearance and demeanor. Short in stature, light in frame, and bony in features, Ravel had the "appearance of a well dressed jockey". His large head seemed suitably matched to his great intellect. He was well read and later accumulated a library of over 1,000 volumes. In his younger adulthood, Ravel was usually bearded in the fashion of the day, though later he dispensed with all whiskers. Though reserved, Ravel was sensitive and self - critical, and had a mischievous sense of humor. He became a life long tobacco smoker in his youth, and he enjoyed strongly flavored meals, fine wine, and spirited conversation.

After failing to meet the requirement of earning a competitive medal in three consecutive years, Ravel was expelled during 1895. He turned down a music professorship in Tunisia then returned to the Conservatoire in 1898 and started his studies with Gabriel Fauré, determined to focus on composing rather than piano playing. He studied composition with Fauré until he was dismissed from the class in 1900 for having won neither the fugue nor the composition prize. He remained an auditor with Fauré until he left the Conservatoire in 1903. Ravel found his teacher’s personality and methods sympathetic and they remained friends and colleagues. He also undertook private studies with André Gedalge, whom he later stated was responsible for "the most valuable elements of my technique." Ravel studied the ability of each instrument carefully in order to determine the possible effects, and was sensitive to their color and timbre. This may account for his success as an orchestrator and as a transcriber of his own piano works and those of other composers, such as Mussorgsky, Debussy and Schumann.

His first significant work, Habanera for two pianos, was later transcribed into the well known third movement of his Rapsodie espagnole, which he dedicated to Charles - Wilfrid de Bériot, another of his professors at the Conservatoire. His first published work was Menuet antique, dedicated to and premiered by Viñes. In 1899, Ravel conducted his first orchestral piece, Shéhérazade, and was greeted by a raucous mixture of boos and applause. The critics were somewhat unfavorable, e.g. reviling him as "a jolting debut: a clumsy plagiarism of the Russian School" and terming him a “mediocrely gifted debutante ... who will perhaps become something if not someone in about ten years, if he works hard.” As the most gifted composer of his class and as a leader, with Debussy, of avant - garde French music, Ravel would continue to have a difficult time with the critics for some time to come.

Around 1900, Ravel joined with a number of innovative young artists, poets, critics, and musicians who were referred to as the Apaches (hooligans), a name coined by Viñes to represent his band of "artistic outcasts". The group met regularly until the beginning of World War I and the members often inspired each other with intellectual argument and performances of their works before the group. For a time, the influential group included Igor Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla. One of the first works Ravel performed for the Apaches was Jeux d'eau, his first piano masterpiece and clearly a pathfinding impressionistic work. Viñes performed the public premiere of this piece and Ravel's other early masterpiece Pavane pour une infante défunte during 1902.

During his years at the Conservatoire, Ravel tried numerous times to win the prestigious Prix de Rome, but to no avail; he was probably considered too radical by the conservatives, including Director Théodore Dubois. One of Ravel's pieces, the String Quartet in F, probably modeled on Debussy’s Quartet (1893), is now a standard work of chamber music, though at the time it was criticized and found lacking academically. After a scandal involving his loss of the prize during 1905 to Victor Gallois, despite being favored to win, Ravel left the Conservatoire. The incident — named the "Ravel Affair" by the Parisian press — engaged the entire artistic community, pitting conservatives against the avant - garde, and eventually caused the resignation of Dubois and his replacement by Fauré, a vindication of sorts for Ravel. Though deprived of the opportunity to study in Rome, the decade after the scandal proved to be Ravel's most productive, and included his "Spanish period".

Ravel met Debussy during the 1890s. Debussy was older than Ravel by some twelve years and his pioneering Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune was influential among the younger musicians including Ravel, who were impressed by the new language of impressionism. During 1900, Ravel was invited to Debussy’s home and they played each other’s works. Viñes became the preferred piano performer for both composers and a go-between. The two composers attended many of the same musical events and were performed at the same concerts. Ravel and the Apaches were strong supporters of Debussy’s controversial public debut of his unconventional opera Pelléas et Mélisande, which garnered Debussy both fame and scorn.

The two musicians also appreciated much the same musical heritage and operated in the same artistic milieu, but they differed in terms of personality and their approach to music. Debussy was considered more spontaneous and casual in his composing while Ravel was more attentive to form and craftsmanship. Even though they worked independently of one another, because they employed differing means to similar ends, and because superficial similarities and even some more substantive ones are evident, the public and the critics associated them more than the facts warranted.

Ravel wrote that Debussy’s “genius was obviously one of great individuality, creating its own laws, constantly in evolution, expressing itself freely, yet always faithful to French tradition. For Debussy, the musician and the man, I have had profound admiration, but by nature I am different from Debussy.” Ravel further stated, “I think I have always personally followed a direction opposed to that of the symbolism of Debussy.”

They admired each other’s music and Ravel even played Debussy’s work in public on occasion. However, Ravel did criticize Debussy sometimes, particularly regarding his orchestration, and he once said, "If I had the time, I would reorchestrate La mer."

By 1905, factions formed for each composer and the two groups began feuding in public. Disputes arose as to questions of chronology about their respective works and who influenced whom. The public tension caused personal estrangement. As Ravel said, “It is probably better after all for us to be on frigid terms for illogical reasons.” Ravel stoically absorbed superficial comparisons with Debussy promulgated by biased critics, including Pierre Lalo, an anti - Ravel critic who stated, “Where M. Debussy is all sensitivity, M. Ravel is all insensitivity, borrowing without hesitation not only technique but the sensitivity of other people.” During 1913, in a remarkable coincidence, both Ravel and Debussy independently produced and published musical settings for poems by Stéphane Mallarmé, again provoking comparisons of their work and their perceived influence on each other, which continued even after Debussy’s death five years later.

The next of Ravel’s piano compositions to become famous was Miroirs (Mirrors, 1905), five piano pieces which marked a “harmonic evolution” and which one commentator described as “intensely descriptive and pictorial. They banish all sentiment in expression but offer to the listener a number of refined sensory elements which can be appreciated according to his imagination.” Next was his Histoires naturelles (Nature Stories), five humorous songs evoking the presence of five animals. Two years later, Ravel completed his Rapsodie espagnole, his first major "Spanish" piece, written first for piano four hands and then scored for orchestra. Though it employs folk - like melodies, no actual folk songs are quoted. It premiered during 1908 to generally good reviews, with one critic stating that it was "one of the most interesting novelties of the season", while Pierre Lalo (as usual) reacted negatively, calling it "laborious and pedantic". Next followed Ravel’s music for the opera L'heure espagnole (The Spanish Hour), full of humor and rich in color, employing a wide variety of instruments and their characteristic qualities, including the trombone, sarrusophone, tuba, celesta, xylophone, and bells.

Ravel further extended his mastery of impressionistic piano music with Gaspard de la nuit, based on a collection by the same name by Aloysius Bertrand, with some influence from the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, particularly in the second part. Viñes, as usual, performed the premiere but his performance displeased Ravel, and their relationship became strained from then on. For future premieres, Ravel replaced Viñes with Marguerite Long. Also unhappy with the conservative musical establishment which was discouraging performance of new music, around this time Ravel, Fauré, and some of his pupils formed the Société musicale indépendante (SMI). During 1910, the society presented the premiere of Ravel’s Ma mère l'oye (Mother Goose) in its original piano duet version. With this work, Ravel followed in the tradition of Schumann, Mussorgsky, and Debussy, who also created memorable works of childhood themes. During 1912, Ravel's Ma mère l'oye was performed as a ballet (with added music) after being first transcribed from piano to orchestra. Looking to expand his contacts and career, Ravel made his first foreign tours to England and Scotland during 1909 and 1911.

Ravel began work with impresario

Sergei Diaghilev during 1909 for the ballet Daphnis et Chloé commissioned by Diaghilev with the lead danced by the famous ballet dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky. Diaghilev had taken Paris by storm the previous year in his Parisian opera debut, Boris Godunov. Daphnis et Chloé took three years to complete, with conflicts constantly arising among the principal artists, including Léon Bakst (sets and costumes), Michel Fokine (libretto), and Ravel (music). In

frustration, Diaghilev nearly cancelled the project. The ballet had an

unenthusiastic reception and lasted only two performances, only to be

revived to acclaim a year later. Igor Stravinsky called Daphnis et Chloé "one

of the most beautiful products of all French music" and author Burnett

James claims that it is "Ravel's most impressive single achievement, as

it is his most opulent and confident orchestral score". The work is notable for its rhythmic diversity, lyricism, and evocations of nature. The score utilizes a large orchestra and two choruses, one onstage and one offstage. So exhausting was the effort to score the ballet that Ravel's health deteriorated, with a diagnosis of neurasthenia soon forcing him to rest for several months. During 1914, just as World War I began, Ravel composed his Piano Trio (for

piano, violin, and cello) with its Basque themes. The piece, difficult

to play well, is considered a masterpiece among trio works.

“it would be dangerous for French composers to ignore systematically the works of their foreign colleagues, and thus form themselves into a sort of national coterie: our musical, so rich at the present time, would soon degenerate and become isolated by its own academic formulas.”

Ravel was exhausted and lacking creative spirit at the war’s end during 1918. With the death of Debussy and the emergence of Satie, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky, modern classical music had a new style to which Ravel would shortly re-group and make his contribution.

Around 1920, Diaghilev commissioned Ravel to write La valse (The Waltz), originally named Wien (Vienna), which was to be used for a projected ballet. The piece, conceived many years earlier, became a waltz with a macabre undertone, famous for its “fantastic and fatal whirling”. However, it was rejected by Diaghilev as “not a ballet. It’s a portrait of ballet”. Ravel, hurt by the comment, ended the relationship. Subsequently, it became a popular concert work and when the two men met again during 1925, Ravel refused to shake Diaghilev's hand. Diaghilev challenged Ravel to a duel, but friends persuaded Diaghilev to recant. The two never met again.

During 1920, the French government awarded Ravel the Légion d'honneur, but he refused it. The next year, he retired to the French countryside where he continued to write music, albeit even less prolifically, but in more tranquil surroundings. He returned regularly to Paris for performances and socializing, and increased his foreign concert tours. Ravel maintained his influential participation with the SMI which continued its active role of promoting new music, particularly of British and American composers such as Arnold Bax, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Aaron Copland, andVirgil Thomson. With Debussy’s death, Ravel became perceived popularly as the main composer of French classical music. As Fauré stated in a letter to Ravel in October 1922, “I am happier than you can imagine about the solid position which you occupy and which you have acquired so brilliantly and so rapidly. It is a source of joy and pride for your old professor.” During 1922, Ravel completed his Sonata for Violin and Cello. Dedicated to Debussy’s memory, the work features the thinner texture popular with the younger postwar composers.

The English, in particular, lauded Ravel, as The Times reported April 16, 1923, “Since the death of Debussy, he has represented to English musicians the most vigorous current in modern French music." In reality, however, Ravel’s own music was no longer considered au courant in France. Satie had become the inspiring force for the new generation of French composers known as Les Six. Ravel was fully aware of this, and was mostly effective in preventing a serious breach between his generation of musicians and the younger group.

In post - war Paris, American musical influence was strong. Jazz particularly was played in the cafes and became popular, and French composers including Ravel and Darius Milhaud were applying jazz elements to their work. Also in vogue was a return to simplicity in orchestration and a transition from the great scale of the works of Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev were in the ascendant, and Arnold Schoenberg's experiments were leading music into atonality. These trends posed challenges for Ravel, always a slow and deliberate composer, who desired to keep his music relevant but still revered the past. This may have played a part in his declining output and longer composing time during the 1920s.

Around 1922, Ravel completed his famous orchestral arrangement of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky, which through its widespread popularity brought Ravel great fame and substantial profit. The first half of the 1920s was a particularly lean period for composing but Ravel did complete successful concert tours to Amsterdam, Milan, London, Madrid, and Vienna, which also boosted his fame. By 1925, by virtue of the unwelcomed pressure of a performance deadline, he finally finished his opera L'enfant et les sortilèges, with its significant jazz and ragtime accents. Famed writer Colette provided the libretto. Around this time, he also completed Chansons madécasses, the summit of his vocal art.

During 1927, Ravel’s String Quartet received its first complete recording. By this time Ravel, like Edward Elgar, had become convinced of the importance of recording his works, especially with his input and direction. He made recordings nearly every year from then until his death. That same year, he completed and premiered his Sonata for Violin and Piano, his last chamber work, with its second movement (titled “Blues”) gaining much attention.

Ravel also served as a juror with Florence Meyer Blumenthal in awarding the Prix Blumenthal, a grant given between 1919 and 1954 to young French painters, sculptors, decorators, engravers, writers, and musicians.

After two months of planning, during 1928 Ravel made a four month concert tour in North America, for a promised minimum of $10,000 (approximately $128,226, adjusted for inflation). In New York City, he received a standing ovation, unlike any of his unenthusiastic premieres in Paris. His all-Ravel concert in Boston was equally acclaimed. The noted critic Olin Downes wrote, “Mr. Ravel has pursued his way as an artist quietly and very well. He has disdained superficial or meretricious effects. He has been his own most unsparing critic.” Ravel conducted most of the leading orchestras in the U.S. from coast to coast and visited twenty - five cities.

He also met the American composer George Gershwin in New York and went with him to hear jazz in Harlem, probably hearing some of the famous jazz musicians such as Duke Ellington. There is a story that when Gershwin met Ravel, he mentioned that he would like to study with the French composer. According to Gershwin, the Frenchman retorted, "Why do you want to become a second rate Ravel when you are already a first rate Gershwin?" The second part of the story has Ravel asking Gershwin how much money he made. Upon hearing Gershwin's reply, Ravel suggested that maybe he should study with Gershwin. This tale may well be apocryphal: Gershwin seems also to have told a near - identical story about a conversation with Arnold Schoenberg, and some have claimed it was with Igor Stravinsky. In any event, this had to have been before Ravel wrote Boléro, which became financially very successful for him.

Ravel then visited New Orleans and imbibed the jazz scene there as well. His admiration of jazz, increased by his American visit, caused him to include some jazz elements in a few of his later compositions, especially the two piano concertos. The great success of his American tour made Ravel famous internationally.

After returning to France, Ravel composed his most famous and controversial orchestral work Boléro, originally called Fandango. Ravel called it “an experiment in a very special and limited direction”. He stated his idea for the piece, “I am going to try to repeat it a number of times on different orchestral levels but without any development.” He conceived of it as an accompaniment to a ballet and not as an orchestral piece as, in his own opinion, “it has no music in it”, and was somewhat taken aback by its popular success. A public dispute began with conductor Arturo Toscanini. The Italian maestro, taking liberties with Ravel’s strict instructions, conducted the piece at a faster tempo and with an “accelerando at the finish”. Ravel insisted “I don’t ask for my music to be interpreted, but only that it should be played.” In the end, the feuding only helped to increase the work’s fame. A Hollywood film titled Bolero (1934), starring Carole Lombard and George Raft, made major use of the theme. Ravel made one of the few recordings of his own music when he conducted his Boléro with the Lamoureux Orchestra in 1930.

Remarkably, Ravel composed both of his piano concertos simultaneously. He completed the Concerto for the Left Hand first. The work was commissioned by Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm during World War I. Ravel was inspired by the technical challenges of the project. As Ravel stated, “In a work of this kind, it is essential to give the impression of a texture no thinner than that of a part written for both hands.” At the premiere of the work, Ravel, not proficient enough to perform the work with only his left hand, played two - handed and Wittgenstein was reportedly underwhelmed by it. But later Wittgenstein stated, “Only much later, after I’d studied the concerto for months, did I become fascinated by it and realized what a great work it was.” In 1933, Wittgenstein played the work in concert for the first time to instant acclaim. Critic Henry Prunières wrote, “From the opening measures, we are plunged into a world in which Ravel has but rarely introduced us.”

The other piano concerto was completed a year later. Its lighter tone follows the models of Mozart, Domenico Scarlatti, and Saint - Saëns, and also makes use of jazz like themes. Ravel dedicated the work to his favorite pianist, Marguerite Long, who played it and popularized it across Europe in over twenty cities, and they recorded it together during 1932. EMI later reissued the 1932 recording on LP and CD. Although Ravel was listed as the conductor on the original 78 - rpm discs, it is possible he merely supervised the recording.

Ravel, ever modest, was bemused by the critics' sudden favor of him since his American tour, “Didn’t I represent to the critics for a long time the most perfect example of insensitivity and lack of emotion?... And the successes they have given me in the past few years are just as unimportant.”

In 1932, Ravel suffered a major blow to the head in a taxi accident. This injury was not considered serious at the time. However, afterwards he began to experience aphasia - like symptoms and was frequently absent minded. He had begun work on music for a film, Adventures of Don Quixote (1933) from Miguel de Cervantes's celebrated novel, featuring the Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin and directed by G.W. Pabst. When Ravel became unable to compose, and could not write down the musical ideas he heard in his mind, Pabst hired Jacques Ibert. However, three songs for baritone and orchestra that Ravel composed for the film were later published under the title Don Quichotte a Dulcinée, and have been performed and recorded.

On April 8, 2008, the New York Times published an article suggesting Ravel may have been in the early stages of frontotemporal dementia during 1928, and this might account for the repetitive nature of Boléro. This accords with an earlier article, published in a journal of neurology, that closely examines Ravel's clinical history and argues that his works Boléro and Piano Concerto for the Left Hand both indicate the impacts of neurological disease. This is contradicted somewhat, however, by the earlier cited comments by Ravel about how he created the deliberately repetitious theme for Boléro.

In late 1937, Ravel consented to experimental brain surgery. One hemisphere of his brain was re-inflated with serous fluid. He awoke from the surgery, called for his brother Édouard, lapsed into a coma and died shortly afterwards at the age of 62. Ravel probably died as a result of a brain injury caused by the automobile accident and not from a brain tumor as some believe. This confusion may arise because his friend George Gershwin had died from a brain tumor only five months earlier. Ravel was buried with his parents in a granite tomb at the cemetery at Levallois - Perret, a suburb of northwest Paris. Ravel is not known to have had any intimate relationships, and his personal life, and especially his sexuality,

remains a mystery. Ravel made a remark at one time suggesting that

because he was such a perfectionist composer, so devoted to his work,

he could never have a lasting intimate relationship with anyone. He is quoted as saying "The only love affair I have ever had was with music". Some of his friends suggested that Ravel frequented the bordellos of Paris, but no factual evidence has ever been found to substantiate this rumor. A

recent hypothesis presented by David Lamaze, a composition teacher at

the Conservatoire de Rennes in France, is that he hid in his music

representations of the nickname and the name of Misia Godebska,

transcribed into two groups of notes, Godebska = G D E B A and Misia =

Mi + Si + A = E B A. He was invited onto her boat during a 1905 cruise

on the Rhine after his failure at the Prix de Rome, for which her husband, Alfred Edwards, organized a scandal in the newspapers. This same man owned the Casino de Paris where the Ravel family had a number staged, Tourbillon de la mort (A

Car Somersault). The family of her half - brother, Cipa Godebski, is said

to have been like a second family for Ravel. In 1907 on Misia's boat L'Aimée, Ravel completed L'heure espagnole and the Rapsodie espagnole, and at the premiere of Daphnis et Chloé, Ravel arrived late and did not go to his box but to Misia's, where he offered her a Japanese doll. In her memoires, Misia hid all these facts.