<Back to Index>

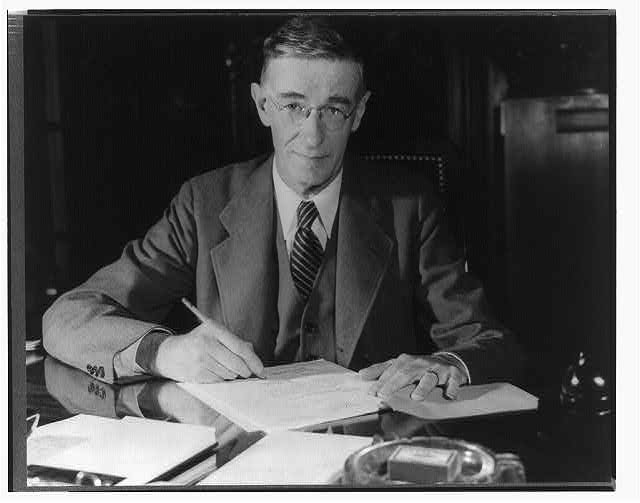

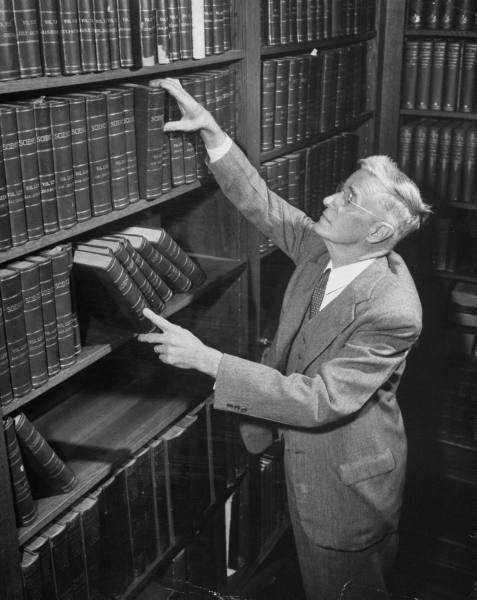

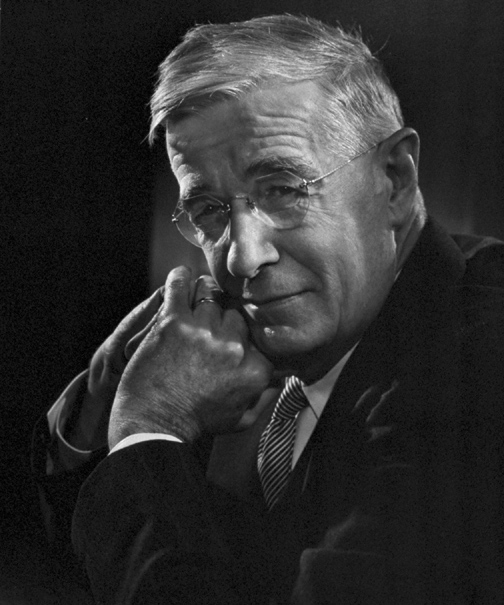

- Engineer Vannevar Bush, 1890

- Composer Anthony Philip Heinrich, 1781

- General of Infantry Ivan Aleksandrovich Nabokov, 1787

PAGE SPONSOR

Vannevar Bush (March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer and science administrator known for his work on analog computing, his political role in the development of the atomic bomb as a primary organizer of the Manhattan Project, the founding of Raytheon, and the idea of the memex, an adjustable microfilm viewer which is somewhat analogous to the structure of the World Wide Web. More specifically, the memex worked as a memory bank to organize and retrieve data. As Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Bush coordinated the activities of some six thousand leading American scientists in the application of science to warfare.

Bush was a well known policymaker and public intellectual during World War II and the ensuing Cold War, and was in effect the first presidential science advisor. Bush was a proponent of democratic technocracy and of the centrality of technological innovation and entrepreneurship for both economic and geopolitical security. Seeing later developments in the Cold War arms race, Bush became troubled. "His vision of how technology could lead toward understanding and away from destruction was a primary inspiration for the postwar research that led to the development of New Media."

Vannevar Bush was born in Everett, Massachusetts. He was educated at Tufts College, graduating in 1913. From mid 1913 to October 1914, Bush worked at General Electric (where he was a supervising "test man"); during the 1914 - 1915 academic year, Bush taught mathematics at Jackson College (the partner school of Tufts). After a summer working as an electrical inspector and a brief stint at Clark University as a doctoral student of Arthur Gordon Webster, Bush entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) electrical engineering program. Bush was vice-president and dean of engineering at MIT from 1932 to 1938. In June 1940 he convinced Franklin Delano Roosevelt to give him funding and political support to create a new kind of collaborative relationship between military, industry, and academic researchers — without congressional, or nearly any other, oversight. This post included many of the powers and functions subsumed by the Provost when MIT introduced this post during 1949 including some appointments of lecturers to specific posts. While at MIT, Bush urged Col. Edward C. Harwood to found the American Institute for Economic Research as an independent, scientific research institute.

Spurred by the need for enough financial security to marry, Bush finished his thesis in less than a year. During August 1916 he married Phoebe Davis, whom he had known since Tufts, in Chelsea, Massachusetts. He received a doctorate in engineering from MIT and Harvard University, jointly, in 1917 — after a dispute with his adviser Arthur Edwin Kennelly, who tried to demand more work from Bush.

During World War I he worked with the National Research Council with about six thousand leading American scientists in the application of science to warfare (such as developing submarines, trip hammers, and better microscopes). He joined the Department of Electrical Engineering at MIT in 1919 and was a professor there from 1923 – 32.

During 1922, Bush and his college roommate, Laurence K. Marshall, set up the American Appliance Company to market a device called the S-tube. This was a gaseous rectifier invented by C.G. Smith that greatly improved the efficiency of radios. Bush made much money from the venture. The company, renamed Raytheon, became a large electronics company and defense contractor.

Starting in 1927, Bush constructed a Differential Analyser, an analog computer that could solve differential equations with as many as 18 independent variables. An offshoot of the work at MIT was the beginning of digital circuit design theory by one of Bush's graduate students, Claude Shannon. During 1939 Bush accepted a prestigious appointment as president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington,

which awarded large sums annually for research. As president, Bush was

able to influence research in the U.S. towards military objectives and

could informally advise the government on scientific matters. During

1939 he became fully involved with politics with his appointment as

chairman of National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which he directed through 1941. Bush remained a member of NACA through 1948. During World War I,

Bush had known the lack of cooperation between civilian scientists and

the military. Concerned about the lack of coordination in scientific

research in the U.S. and the need for mobilization for defense, Bush in

1939 proposed a general directive agency in the federal government, which he often discussed with his colleagues at NACA, James B. Conant (President of Harvard University), Karl T. Compton (President of M.I.T.), and Frank B. Jewett, President of the National Academy of Sciences. Bush

continued to urge for the agency's creation. Early in 1940, at Bush's

suggestion, the secretary of NACA began preparing a draft of the

proposed National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) to be presented to Congress. But when the Germans invaded France, Bush decided speed was important and signalled President Roosevelt directly.

He managed to get a meeting with the President on 12 June 1940 and took

a single sheet of paper describing the proposed agency. Roosevelt

approved it in ten minutes. NDRC was functioning, with Bush as chairman and others as members, even before the agency was made official by order of the Council of National Defense on June 27, 1940. Bush quickly appointed four leading scientists to NRDC: NACA colleagues Conant, Compton, and Jewitt, and also Richard C. Tolman, dean of the graduate school at Caltech. Each was assigned an area of responsibility. Compton was in charge of radar,

Conant of chemistry and explosives, Jewitt of armor and ordnance, and

Tolman of patents and inventions. Government officials then complained

that Bush was attempting to by-pass them and to acquire more authority

for himself. Bush later agreed: "That, in fact, is exactly what it

was." This co-ordination of scientific effort was instrumental for the

Allies winning the Second World War. Alfred Loomis

said that "Of the men whose death in the summer of 1940 would have been

the greatest calamity for America, the President is first,

and Dr. Bush would be second or third." During 1941 the NDRC was subsumed into the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) with Bush as director, which controlled the Manhattan Project until 1943 (when administration was assumed by the Army) and which also coordinated scientific research during World War II. In all, OSRD directed 30,000 men and oversaw development of some 200 weapons and instrumentalities of war, including nuclear weapons, sonar, radar, the proximity fuze, amphibious vehicles, and the Norden bomb sight, all considered critical in winning the war. At one time, two - thirds of

all the nation’s physicists were working under Bush’s direction. In

addition, OSRD contributed to many advances of the physical sciences

and medicine, including the mass production of penicillin and sulfa drugs. Of the war, Bush said in "As We May Think",

"This has not been a scientist's war; it has been a war in which all

have had a part. The scientists, burying their old professional

competition in the demand of a common cause, have shared greatly and

learned much." Another

good example of the close working relationship between Bush and

President Roosevelt was in a brief memo, dated March 20, 1942,

providing approval for development of the atom bomb and

what became the Manhattan Project. Roosevelt wrote Bush, "I have read

your extremely interesting report and I agree that the time has come

for a review of the work of the Office on New Weapons.... I am

returning the report for you to lock up, as I think it is probably

better that I should not have it in my own files." Bush's

method of management at OSRD was to direct overall policy while

delegating supervision of divisions to qualified colleagues and letting

them do their jobs without interference. He attempted to interpret the

mandate of OSRD as narrowly as possible to avoid overtaxing his office

and to prevent duplicating the efforts of other agencies. Other

problems were obtaining adequate funds from the President and Congress

and determining apportionment of research among government, academic,

and industrial facilities. However, his most difficult problems, and

also greatest successes, were keeping the confidence of the military,

which distrusted the ability of civilians to observe security

regulations, and opposing conscription of young scientists into the

armed forces. The New York Times in

its obituary described him as “a master craftsman at steering around

obstacles, whether they were technical or political or bull - headed

generals and admirals.” Dr. Conant commented, “To see him in action

with the generals was an exhibit.” OSRD

continued to function actively until some time after the end of

hostilities, but by 1946 and 1947 it had been reduced to a minimal

staff charged with finishing work remaining from the war period. Bush

and many others had hoped that with the dissolution of OSRD, an

equivalent peacetime government research and development agency would

replace it. Bush felt that basic research was important national

survival for both military and commercial reasons, requiring continued

government support for science and technology. Technical superiority

could be a deterrent to future enemy aggression. During July 1945, in

his report to the President Science, The Endless Frontier,

Bush wrote that basic research was: "the pacemaker of technological

progress” and "New products and new processes do not appear full - grown.

They are founded on new principles and new conceptions, which in turn

are painstakingly developed by research in the purest realms of

science!" He recommended the creation of what would eventually become

in 1950 the National Science Foundation (NSF). Simultaneously during July 1945, the Kilgore bill was

introduced in Congress proposing a single science administrator

appointed and removable by the President, with emphasis on applied

research, and a patent clause favoring a government monopoly. In

contrast, the competing Magnuson bill was similar to Bush's proposal to

vest control in a panel of top scientists and civilian administrators

with the executive director appointed by them, to emphasize basic

research, and to protect private patent rights. A compromise Kilgore -

Magnuson bill of February 1946 passed the Senate but expired in

the House because Bush favored a competing bill that was a virtual

duplicate of the original Magnuson bill. During

February 1947, a Senate bill was introduced to create the National

Science Foundation to replace OSRD, favoring most of the features

advocated by Bush, including the controversial administration by an

autonomous scientific board. It passed the Senate on May 20 and the

House on July 16, but was vetoed by Truman on August 6 on the grounds

that the administrative officers were not properly responsible to

either the President or Congress. In the meantime Bush was still director of what was left of OSRD and fulfilling his duties as president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. In addition, Bush postwar had helped create the Joint Research and Development Board (JRDB) of the Army and Navy, of which he was chairman. With passage of the National Security Act,

signed into law during late July 1947, the JRDB became the Research and

Development Board (RDB). It was to promote research through the

military until a bill creating the National Science Foundation finally

became law. It

was assumed President Truman would naturally appoint Bush chairman of

the new agency, and behind the scenes Bush was lobbying for the

position. But Truman was displeased with the form of the just - vetoed

NSF bill favored by Bush, considering it an attempt by Bush to acquire

power. His misgivings about Bush were revealed publicly on September 3,

1947: He wanted more time to think about it and reportedly told his

defense chiefs that if he did appoint Bush, he planned to keep a close

eye on him. However, Truman finally relented. On September 24 Bush met

with Truman and Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, where Truman offered the position to Bush. Initially

the RDB had a budget of 465 million dollars to be spent on "research

and development for military purposes." Late during 1947, a directive

issued by Forrestal further defined the duties of the board and

assigned it the responsibility and authority to "resolve differences

among the several departments and agencies of the military

establishment." However,

the authority Bush had as chairman of the RDB was much different from

the power and influence he enjoyed as director of OSRD and the agency

he hoped to create postwar almost independent of the Executive branch

and Congress. Bush was never happy with the position and resigned as

chairman of the RDB after a year, but remained on the oversight

committee. Despite

his later ambiguous relationship with Truman, Bush’s advice on various

scientific and political matters was often sought by Truman. When

Truman became President and first learned of the atomic bomb, Bush

briefed him on the scientific aspects. Soon after, during June 1945,

Bush was on the committee advising Truman to use the atomic bomb against Japan at the earliest opportunity. In Pieces of the Action,

Bush wrote that he thought use of the bomb would shorten the war and

prevent many American casualties. Bush's vision of how to apply the

lessons of OSRD to peacetime, Science, The Endless Frontier,

was commissioned by Roosevelt in a letter of Nov 1944, was written

during the following months, and — Roosevelt having died in the

meantime — delivered to Truman in July 1945. Immediately after the war, there were debates about future uses of atomic energy and

whether it should be placed under international control. During early

1946, Bush was appointed to a committee to develop a plan for United Nations control.

According to Truman in his memoirs, Bush advised him that a proposal to

Russia for exchange of scientific information would promote international collaboration and eventually effective control, the

alternative being an atomic bomb race. Bush wrote in a memo, “The move

does not involve ‘giving away the secret of the atomic bomb’. That

secret resides principally in the details of construction of the bombs

themselves, and in the manufacturing process. What is given and what is

received is scientific knowledge.” Bush felt that attempts to maintain

scientific secrets from the Russians would be of little benefit to the

U.S. since they would probably obtain such secrets anyway through

espionage while most American scientists would be kept ignorant of

Soviet science. During

September 1949, Bush was also appointed to a scientific committee

reviewing the evidence that Russia had just tested its first atomic

bomb. The conclusions were relayed to Truman who then made the public

announcement. Bush continued to serve on NACA through 1948 and expressed annoyance with aircraft companies for delaying development of a turbojet engine because of the huge expense of research and development plus retooling from older piston engines. From 1947 to 1962 Bush was also on the board of directors of American Telephone and Telegraph.

During 1955 Bush retired as President of the Carnegie Institution and

returned to Massachusetts. From 1957 to 1962 he was chairman of the

large pharmaceutical corporation Merck & Co.. One of Bush's PhD students at MIT was Frederick Terman, who was later instrumental in the development of "Silicon Valley". Canadian government documents from 1950 and 1951 involving the Canadian Defence Research Board, Department of Transport, and Embassy in Washington D.C., implicate Bush as directing a very secret UFO study group within the U.S. Research and Development Board. Bush was opposed to the introduction of Nazi scientists into the U.S. under the secretive Project Paperclip, thinking that they were potentially a danger to democracy. Bush

believed in a strong national defense and the role that scientific

research played in it. However in an interview on his 80th birthday he

expressed reservations about the arms race he had helped to create. “I

do think the military is too big now —- I think we’ve overdone putting

bases all over the world.” He also expressed opposition to the antiballistic missile (ABM) because it would damage arms limitation talks with the Soviets and because “I don’t think the damn thing will work.” Bush

and his wife Phoebe had two sons: Richard Davis Bush and John Hathaway

Bush. Vannevar Bush died at age 84 from pneumonia after suffering a

stroke during 1974 in Belmont, Massachusetts. A lengthy obituary was published on the front page of the New York Times on June 30. Bush introduced the concept of what he called the memex (possibly derived from "memory extension") during the 1930s, which he imagined as a microfilm -

based

"device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and

communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted

with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate

supplement to his memory." He wanted the memex to behave like the

"intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain";

essentially, causing the proposed device to be similar to the functions

of a human brain. It was also important that it could be easily

accessible '"a future device for individual use... a sort of mechanized

private file and library" in the shape of a desk'. The important

feature of the memex is that it ties two pieces together. Any item can

lead to another immediately. Bush explains how the human mind works

differently than traditional storage paradigms. For example, data is

often stored alphabetically, and to retrieve it one must trace it down

from subclass to subclass. The brain, Bush explains, works by

association rather than index, and with the brain being one of the "awe

- inspiring" phenomena in nature, one should learn from it. After thinking about the potential of augmented memory for several years, Bush set out his thoughts at length in the essay "As We May Think" in the Atlantic Monthly, which was published July 1945. In the article, Bush predicted that "wholly new forms of encyclopedias will

appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through

them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified". A few

months later (10 September 1945) Life magazine published

a condensed version of "As We May Think", accompanied by several

illustrations showing the possible appearance of a memex machine and

its companion devices. Michael Buckland, a library scientist, regards the memex as severely flawed and blames it on a limited understanding by Bush of both information science and microfilm. Bush did not refer in his popular essay to the microfilm based workstation proposed by Leonard Townsend during 1938, or the microfilm and electronics based selector described in more detail and patented by Emanuel Goldberg during 1931. Shortly after "As We May Think" was published, Douglas Engelbart came

across Bush's piece. With the concepts of Bush's visions in mind, he

would begin work that would later lead to the invention of the mouse,

word processor, and hyperlink. Ted Nelson, who coined the terms hypertext and hypermedia, also became greatly influenced by Bush's essay. He would also discover the hyperlink separate from Engelbart's discovery.

Due to the linear fashion of the memex machine, the term

Bushian

has been coined to express the linearity of

HTML structure

and text. The Bushian philosophy of digital media is more focused on

using facts to build something creative that will better our world.

Bush sees art as a tool to help with that process. Instead of using

emotion as a base, the Bushian view uses reason and logic. His goal is

to untangle the labyrinth shaped book and mold it into something linear

and reasonable. Bush is constantly in search of a shortcut to the end

of the trial. The Bushian concept of linearity is the opposite of Borgesian, a term coined to express the non linear philosophy of Jorge Luis Borges.