<Back to Index>

- Physiologist Emil Adolf von Behring, 1854

- Composer Eduard Strauss, 1835

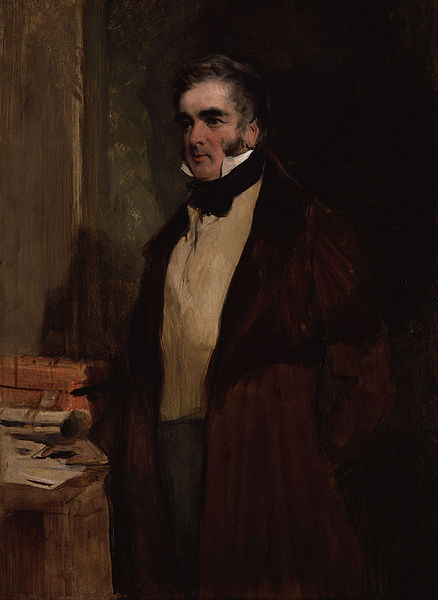

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, 1779

PAGE SPONSOR

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, PC, FRS (15 March 1779 – 24 November 1848) was a British Whig statesman who served as Home Secretary (1830 – 1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835 – 1841), and was a mentor of Queen Victoria. The second largest city in Australia, Melbourne, was named in his honour.

Born in London to an aristocratic Whig family and educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, he fell in with a group of Romantic Radicals that included Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. In 1805 he succeeded his elder brother as heir to his father's title and he married Lady Caroline Ponsonby. The next year he was elected to the British House of Commons as the Whig MP for Leominster. For the election in 1806 he was moved to the seat of Haddington burghs and for the 1807 election successfully stood for Portarlington (a seat he held until 1812).

He first came to general notice for reasons he would rather have avoided: his wife had a public affair with Lord Byron — she coined the famous characterisation of him as "mad, bad, and dangerous to know". The resulting scandal was the talk of Britain in 1812. Eventually the two reconciled and though they separated in 1825, her death in 1828 affected him considerably.

In 1816 Lamb was returned for Peterborough by Whig grandee Lord Fitzwilliam. He told Lord Holland that he was committed to the Whig principles of the Glorious Revolution but not to "a heap of modern additions, interpolations, facts and fictions". He therefore spoke against parliamentary reform and voted for the suspending of habeas corpus in 1817 when sedition was rife.

Lamb's hallmark was finding the middle ground. Though a Whig, he accepted the post of Irish Secretary (1827) in the moderate Tory governments of George Canning and Lord Goderich. Upon the death of his father in 1828 and his becoming Viscount Melbourne, he moved to the House of Lords.

When the Whigs came to power under Lord Grey in November 1830 he became Home Secretary in the new government. During the disturbances of 1830 – 32 Melbourne "acted both vigorously and sensitively, and it was for this function that his reforming brethren thanked him heartily". In the aftermath of the Swing Riots of 1830 – 31 he countered the Tory magistrates' alarmism by refusing to resort to military force and instead he advocated magistrates' usual powers be fully enforced along with special constables and financial rewards for the arrest of rioters and rabble - rousers. He appointed a special commission to try approximately one thousand of those arrested and ensured that justice was strictly adhered to: one third were acquitted; and most of the one - fifth sentenced to death were instead transported. The disturbances over reform in 1831 – 32 were countered with the enforcement of the usual laws and again Melbourne refused to pass emergency legislation against sedition.

After Lord Grey resigned as Prime Minister in July 1834, the King was forced to appoint another Whig to replace him, as the Tories were not strong enough to support a government. Melbourne was the man most likely to be both acceptable to the King and hold the Whig party together. Melbourne hesitated after receiving from Grey the letter from the King requesting him to visit him to discuss the formation of a government. Melbourne thought he would not enjoy the extra work that accompanied the office of Premier but he did not want to let his friends and party down. According to Charles Greville, Melbourne said to his secretary, Tom Young: "I think it's a damned bore. I am in many minds as to what to do". Young replied: "Why, damn it all, such a position was never held by any Greek or Roman: and if it only lasts three months, it will be worth while to have been Prime Minister of England [sic]". "By God, that's true," Melbourne said, "I'll go!"

Compromise was the key to many of Melbourne's actions. He was opposed in theory to the radical governmental reforms proposed by the Whigs, but reluctantly believed that they were necessary to forestall the threat of revolution. While he was less radical than many, when Lord Grey resigned (July 1834), Melbourne was widely seen as the most acceptable replacement among the Whig leaders, and became Prime Minister.

King William IV's opposition to the Whigs' reforming ways led him to dismiss Melbourne in November. He then gave the Tories under Sir Robert Peel an opportunity to form a government. Peel's failure to win a House of Commons majority in the resulting general election (January 1835) made it impossible for him to govern, and the Whigs returned to power under Melbourne in April 1835. This was the last time a British monarch attempted to appoint a government against parliamentary majority.

The next year, Melbourne was once again involved in a sex scandal. This time he was the victim of attempted blackmail from the husband of a close friend, society beauty and author Caroline Norton. The husband demanded £1400, and when he was turned down he accused Melbourne of having an affair with his wife. In the early 19th century even one sexual scandal (like the one two decades earlier involving Lord Byron) would be enough to finish off the career of most men, so it is a measure of the respect contemporaries had for his integrity that Melbourne's government did not fall. After Mr. Norton was unable to produce any evidence of an affair, the scandal died away.

Nonetheless, as Boyd Hilton records, "it is irrefutable that Melbourne's personal life was problematic. Spanking sessions with aristocratic ladies were harmless, not so the whippings administered to orphan girls taken into his household as objects of charity."

Melbourne was Prime Minister when Queen Victoria came

to the throne (June 1837). Barely eighteen, she was only just breaking free from the domineering influence of her mother, the Duchess of Kent, and her mother's advisor, John Conroy.

Over the next four years Melbourne trained her in the art of politics

and the two became friends: Victoria was quoted as saying she

considered him like a father (her own had died when she was only eight

months old), and Melbourne's daughter had died at a young age.

Melbourne was given a private apartment at Windsor Castle, and unfounded rumours circulated for a time that Victoria would marry Melbourne, forty years her senior. In May 1839, Melbourne's resignation led to the Bedchamber Crisis. Prospective prime minister Robert Peel requested

that Victoria dismiss some of the wives and daughters of Whig MPs who

made up her personal entourage, arguing that the monarch should avoid

any hint of favouritism to a party out of power. As the Queen refused

to comply (a course supported by the Whigs) Peel refused to form a new

government and Melbourne was eventually persuaded to stay on as Prime

Minister. On 25 February 1841, he was admitted a Fellow of the Royal Society. Melbourne

left a considerable list of reforming legislation – not as long as that

of Lord Grey, but worthy nonetheless. Among his administration's acts

were a reduction in the number of capital offences, reforms of local

government, and the reform of the Poor laws. This restricted the terms on which the poor were allowed relief and established compulsory admission to workhouses for the impoverished. Even

after Melbourne resigned permanently in August 1841, Victoria continued

writing to him but eventually the correspondence ceased as it was seen

as inappropriate. Melbourne's role faded away as Victoria came to rely

on her new husband Prince Albert as well as on herself. On his death his titles passed to his brother Frederick. The city of Melbourne, Australia, was named in his honour in March 1837, as he was the Prime Minister at the time. Another

lasting memorial is his favourite, and most famous, dictum in politics:

"Why not leave it alone?", quoted by those who object to change for

change's sake.