<Back to Index>

- Geologist William "Strata" Smith, 1769

- Writer Aleksey Feofilaktovich Pisemsky, 1821

- Governor General of Angola José Maria Mendes Ribeiro Norton de Matos, 1867

PAGE SPONSOR

William 'Strata' Smith (23 March 1769 – 28 August 1839) was an English geologist, credited with creating the first nationwide geological map. He is known as the "Father of English Geology" for collating the geological history of England and Wales into a single record, although recognition was very slow in coming. At the time his map was first published he was overlooked by the scientific community; his relatively humble education and family connections preventing him from mixing easily in learned society. Consequently his work was plagiarised, he was financially ruined, and he spent time in debtors' prison. It was only much later in his life that Smith received recognition for his accomplishments.

Smith was born in the village of Churchill, Oxfordshire, the son of blacksmith John Smith, himself scion of a respectable farming family. His father died when Smith was just eight years old, and he was then raised by his uncle. In 1787, he found work as an assistant for Edward Webb of Stow - on - the - Wold, Gloucestershire, a surveyor. He was quick to learn, and soon became proficient at the trade. In 1791, he traveled to Somerset to make a valuation survey of the Sutton Court estate, and building on earlier work in the same area by John Strachey. He stayed there for the next eight years, working first for Webb and later for the Somersetshire Coal Canal Company.

Below is an extract from his writings in which he describes his experiences when living in High Littleton & Bath Somerset.

I resided from 1791 - 1795 in a part of the large old manor house belonging to Lady JONES called Rugburn in High Littleton. It was then occupied by a farmer [Cornelius HARRIS], who lodged and boarded me for half a guinea a week and kept my horse for half a crown a week. I have often said that in one respect my residence was the most singular, it being nearer to three cities than any other place in Britain: it is 10 miles from Bath, 10 from Bristol and 12 from Wells. What is called the lower road from Bath to Wells goes through High Littleton but Rugburn old house is a quarter of a mile east of the village and about half way between it and Mearns coal pit. It is a large quadrangular house, I believe with a double M roof; several of the windows used to be darkened [filled up]. There was a square walled court in front with entrance gates between brick pillars on top of a flight of stone steps and on each side of the gates facing the south was a niche in the wall, where I used to sit and study. On the one side of the court was a row of lime trees, which screened it from the farmyard and the east wind, and on the other side was a large walled garden, and over the road of approach there was an avenue of fine elms all across a large piece of pasture. This had been the coach road when the house was occupied, as I understand, by a Major [Capt. John] BRITTON, who, according to the account of the old farmer, was said to have ruined himself by working the coal upon his own estate [BRITTON's half brother, William JONES of Stowey, baled him out with a loan of £1,200, in return for which BRITTON left JONES his High Littleton estates and lordship of the manor on his death in 1742]. I collected much information from the old colliers respecting the coal, ancient collieries, faults re which I must herein omit; but I must be rather particular in describing the house, through it's [sic] relation to the now extensively known science of geology; for, as some of my pupils and friends have called the vicinity of Bath the cradle of geology. I now inform them that RUGBURN WAS IT'S [sic] BIRTHPLACE.

Smith worked at one of the estate's older mines, the Mearns Pit at High Littleton, part of the Somerset coalfield and the Somerset Coal Canal. As he observed the rock layers (or strata)

at the pit, he realised that they were arranged in a predictable

pattern and that the various strata could always be found in the same

relative positions. Additionally, each particular stratum could be

identified by the fossils it contained, and the same succession of fossil groups

from older to younger rocks could be found in many parts of England.

Furthermore, he noticed an easterly dip of the beds of rock - small

near

the surface (about three degrees) then bigger after the Triassic rocks. This gave Smith a testable hypothesis, which he termed The Principle of Faunal Succession,

and he began his search to determine if the relationships between the

strata and their characteristics were consistent throughout the

country. During subsequent travels, first as a surveyor (appointed by

noted engineer John Rennie)

for the canal company until 1799 when he was dismissed, and later, he

was continually taking samples and mapping the locations of the various

strata, and displaying the vertical extent of the strata, and drawing

cross - sections and tables of what he saw. This would earn him the name

"Strata Smith". As a natural consequence, Smith amassed a large and

valuable collection of fossils of the strata he had examined himself from exposures in canals, road and railway cuttings, quarries and escarpments across the country.

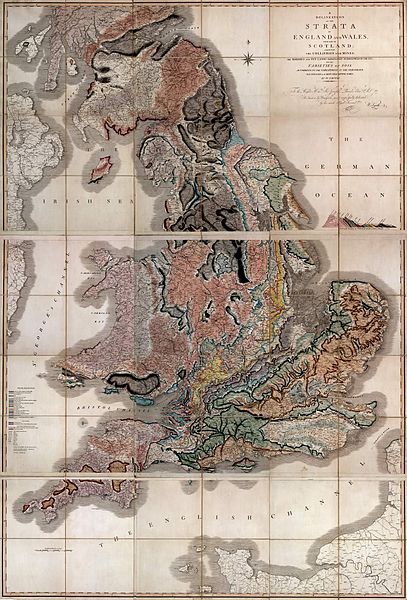

In 1799 Smith produced the first large scale geologic map of the area around Bath, Somerset. Previously, he only knew how to draw the vertical extent of the rocks, but not how to display them horizontally. However, in the Somerset County Agricultural Society, he found a map showing the types of soils and vegetation around Bath and their geographical extent. Importantly, the differing types were coloured. Using this technique, Smith could draw a geological map from his observations showing the outcrops of the rocks. He took a few rock types, each with its own colour. Then he estimated the boundaries of each of the outcrops of rock, filled them in with colour and ended up with a crude geological map.

In

1801, he drew a rough sketch of what would become "The Map that Changed

the World". Because he was unemployed, he could travel across the

length and breadth of the country, while meeting some eminent people

such as Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester, and the Duke of Bedford.

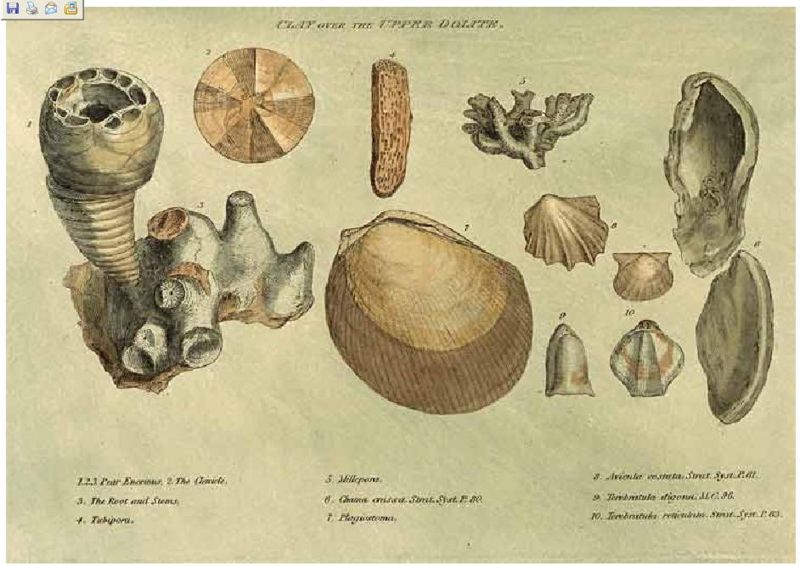

In 1815 he published the first geological map of Britain. It covered the whole of England and Wales, and parts of Scotland. Conventional symbols were used to mark canals, tunnels, tramways and roads, collieries, lead, copper and tin mines, together with salt and alum works. The various geological types were indicated by different colours; the maps were hand coloured. Nevertheless, the map is remarkably similar to modern geological maps of England. He also published his Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales in the same year. In this work he recognised that strata contained distinct fossil assemblages which could be used to match rocks across regions.

In 1817 he drew a remarkable geological section from Snowdon to London. Unfortunately, his maps were soon plagiarised and sold for prices lower than he was asking. He went into debt and finally became bankrupt.

On 31 August 1819 Smith was released from King's Bench Prison in London, a debtor's prison. He returned to his home of fourteen years at 15 Buckingham Street to find a bailiff at the door and his home and property seized. Smith then worked as an itinerant surveyor for many years until one of his employers, Sir John Johnstone, recognised him and took steps to gain for him the respect he deserved. Between 1824 and 1826 he lived and worked in Scarborough, and was responsible for the building of the Rotunda, a geological museum devoted to the Yorkshire coast.The Rotunda was re-opened as 'Rotunda - The William Smith Museum of Geology', on 9 May 2008 by Lord Oxburgh, however, the Prince of Wales visited the Rotunda as early as 14 September 2007 to view the progress of the refurbishment of this listed building.

It was not until February 1831 that the Geological Society of London conferred on Smith the first Wollaston Medal in recognition of his achievement. It was on this occasion that the President, Adam Sedgwick, referred to Smith as "the Father of English Geology". Smith travelled to Dublin with the British Association in 1835, and there totally unexpectedly received an honorary Doctorate of Laws (LL.D.) from Trinity College. In 1838 he was appointed as one of the commissioners to select building - stone for the new Palace of Westminster. He died in Northampton, and is buried a few feet from the west tower of St Peter's Church, Marefair.

The inscription on the grave is badly worn but the name "William Smith"

can just be seen. The modern geological map of Britain is based on

Smith's original work, his map being displayed at the Geological Society in London, although now protected by a curtain.

- The first geological map of Britain, much copied in his time, and the basis for all others.

- Geological Surveys around the world owe a debt to his work.

- His nephew John Phillips lived during his youth with William Smith and was his apprentice. John Phillips became a major figure in 19th century geology and paleontology — among other things he's credited as first to specify most of the table of geologic eras that is used today (1841).

- A crater on Mars is named after him.

- The Geological Society of London presents an annual lecture in his honour.

- In 2005, a William Smith 'facsimile' was created at the Natural History Museum as a notable gallery character to patrol its displays, among other luminaries such as Carl Linnaeus, Mary Anning, and Dorothea Bate.