<Back to Index>

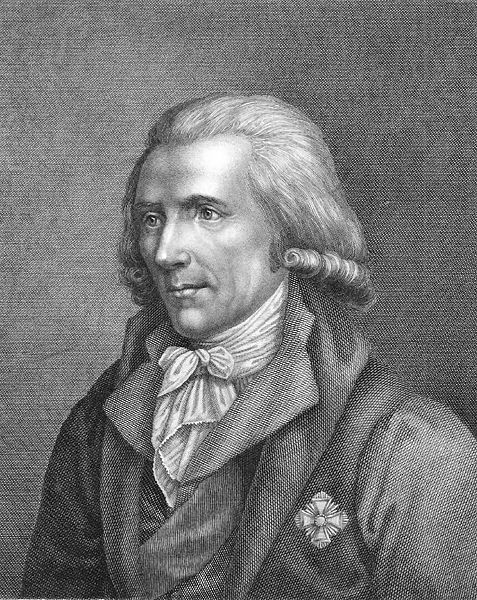

- Physicist Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, 1753

- Writer Edward Bellamy, 1850

- Imperial Regent of Japan Toyotomi Hideyoshi, 1537

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (in German: Reichsgraf von Rumford), FRS (March 26, 1753 – August 21, 1814) was an Anglo - American physicist and inventor whose challenges to established physical theory were part of the 19th century revolution in thermodynamics. He also served as a Colonel in the Loyalist forces in America during the American Revolutionary War. After the end of the war he moved to London where his administrative talents were recognized when he was appointed a junior minister in the British government, and in 1784 received a knighthood from King George III. A prolific designer, he also drew designs for warships. He later moved to Bavaria and entered government service there, being appointed Bavarian Army Minister and re-organizing the army, and, in 1791, was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire.

Thompson was born in rural Woburn, Massachusetts, on March 26, 1753; his birthplace is preserved as a museum. He was educated mainly at the village school, although he sometimes walked to Cambridge with the older Loammi Baldwin to attend lectures by Professor John Winthrop of Harvard College. At the age of 13 he was apprenticed to John Appleton, a merchant of nearby Salem. Thompson excelled at his trade, and coming in contact with refined and well educated people for the first time, adopted many of their characteristics, including an interest in science. While recuperating in Woburn in 1769 from an injury, Thompson conducted experiments concerning the nature of heat and began to correspond with Loammi Baldwin and others about them. Later that year, he worked for a few months for a Boston shopkeeper and then apprenticed himself briefly, and unsuccessfully, to a doctor in Woburn.

Thompson's

prospects were dim in 1772 but in that year they changed abruptly. He

met, charmed and married a rich and well connected heiress named Sarah

Rolfe, her father was minister and her late husband left her property

at Concord, then called Rumford. They moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and through his wife's influence with the governor, was appointed a major in a New Hampshire Militia.

When the American Revolution began, Thompson was a man of property and standing in New England, and was opposed to the rebels. He was active in recruiting loyalists to fight the rebels. This earned him the enmity of the popular party, and a mob attacked Thompson's house. He fled to the British lines, abandoning his wife, as it turned out, forever. Thompson was welcomed by the British, to whom he gave valuable information about the American forces, and became an advisor to both General Gage and Lord George Germain.

While working with the British armies in America, he conducted experiments concerning the force of gunpowder, the results of which were widely acclaimed when eventually published, in 1781, in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Thus, when he moved to London at the conclusion of the war, he already had a reputation as a scientist.

In 1785, he moved to Bavaria where he became an aide - de - camp to the Prince - elector Karl Theodor. He spent eleven years in Bavaria, reorganizing the army and establishing workhouses for the poor. He also invented Rumford's Soup, a soup for the poor, and established the cultivation of the potato in Bavaria. He studied methods of cooking, heating, and lighting, including the relative costs and efficiencies of wax candles, tallow candles, and oil lamps. He also founded the Englischer Garten in Munich in

1789; it remains today and is known as one of the largest urban public

parks in the world. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1789. For his efforts, in 1791 Thompson was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, with the title of Reichsgraf von Rumford (English: Count Rumford).

His experiments on gunnery and explosives led to an interest in heat. He devised a method for measuring the specific heat of a solid substance but was disappointed when Johan Wilcke published his parallel discovery first.

Thompson next investigated the insulating properties of various materials, including fur, wool and feathers. He correctly appreciated that the insulating properties of these natural materials arise from the fact that they inhibit the convection of air. He then made the somewhat reckless, and incorrect, inference that air and, in fact, all gases, were perfect non-conductors of heat. He further saw this as evidence of the argument from design, contending that divine providence had arranged for fur on animals in such a way as to guarantee their comfort.

In 1797, he extended his claim about non-conductivity to liquids. The idea raised considerable objections from the scientific establishment, John Dalton and John Leslie making particularly forthright attacks. Instrumentation far exceeding anything available in terms of accuracy and precision would have been needed to verify Thompson's claim. Again, he seems to have been influenced by his theological beliefs and it is likely that he wished to grant water a privileged and providential status in the regulation of human life.

However, Rumford's most important scientific work took place in Munich, and centered on the nature of heat, which he contended in An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction (1798) was not the caloric of then current scientific thinking but a form of motion. Rumford had observed the frictional heat generated by boring cannon at the arsenal in Munich. Rumford immersed a cannon barrel in water and arranged for a specially blunted boring tool. He showed that the water could be boiled within roughly two and a half hours and that the supply of frictional heat was seemingly inexhaustible. Rumford confirmed that no physical change had taken place in the material of the cannon by comparing the specific heats of the material machined away and that remaining. Rumford argued that the seemingly indefinite generation of heat was incompatible with the caloric theory. He contended that the only thing communicated to the barrel was motion.

Rumford

made no attempt to further quantify the heat generated or to measure

the mechanical equivalent of heat. Though this work met with a hostile

reception, it was subsequently important in establishing the laws of conservation of energy later in the 19th century.

He

regarded coldness to be more than just the absence of heat, but as

something real and did experiments to support his theories of calorific

and frigorific radiation and said the communication of heat was the net

effect of caloric (hot) rays and frigorific (cold) rays.

Thompson was an active and prolific inventor, developing improvements for chimneys and fireplaces and inventing the double boiler, a kitchen range, and a drip coffeepot. The Rumford fireplace is a much more efficient way to heat a room than earlier fireplaces, and created a sensation in London when he introduced the idea of restricting the chimney opening to increase the updraught. He and his workers changed fireplaces by inserting bricks into the hearth to make the side walls angled and added a choke to the chimney to increase the speed of air going up the flue. It effectively produced a streamlined air flow, so all the smoke would go up into the chimney rather than lingering, entering the room and often choking the residents. It also had the effect of increasing the efficiency of the fire, and gave extra control of the rate of combustion of the fuel, whether wood or coal. Many fashionable London houses were modified to his instructions, and became smoke-free. Thompson became a celebrity when news of his success became widespread.

His work was also very profitable, and much imitated when he published his analysis of the way chimneys worked. In many ways, he was similar to Benjamin Franklin, who also invented a new kind of heating stove.

He invented a percolating coffee pot following his pioneering work with the Bavarian Army, where he improved the diet of the soldiers as well as their clothes.

The retention of heat was a recurring theme in his work, as he is also credited with the invention of thermal underwear.

Rumford worked in

photometry, the measurement of light. He made a photometer and introduced the standard candle, the predecessor of the candela, as a unit of luminous intensity. His standard candle was made from the oil of a sperm whale, to rigid specifications. He

also published studies of "illusory" or subjective complementary

colors, induced by the shadows created by two lights, one white and one

colored; these observations were cited and generalized by Michel - Eugène Chevreul as his "law of simultaneous color contrast" in 1839.

Thompson endowed the Rumford medals of the Royal Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and endowed a professorship at Harvard University. In 1803, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 1804, he married Marie - Anne Lavoisier, the widow of the great French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, his American wife having died since his emigration. They separated after a year, but Thompson settled in Paris and

continued his scientific work until his death on August 21, 1814.

Thompson is buried in the small cemetery of Auteuil in Paris, just

across from Adrien - Marie Legendre. Upon his death, his daughter from his first marriage, Sarah Thompson, inherited his title as Countess Rumford.