<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Yegor Ivanovich Zolotarev, 1847

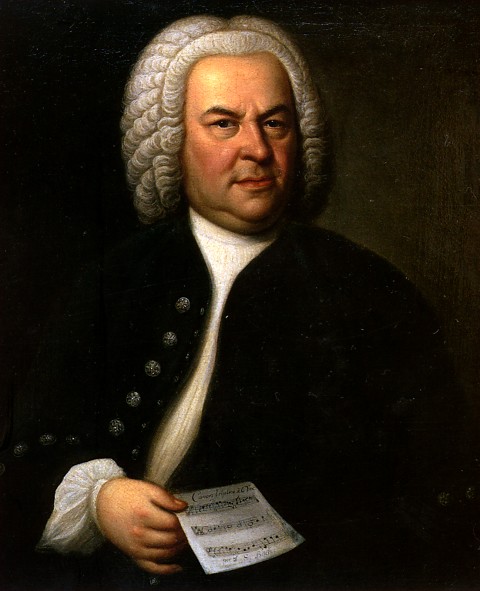

- Composer Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685

- Emperor of the Roman Empire Marcus Flavius Valerius Constantius Herculius Augustus, 250

PAGE SPONSOR

Johann Sebastian Bach (21 March 1685, O.S.31 March 1685, N.S. – 28 July 1750, N.S.) was a German composer, organist, harpsichordist, violist, and violinist whose sacred and secular works for choir, orchestra, and solo instruments drew together the strands of the Baroque period and brought it to its ultimate maturity. Although he did not introduce new forms, he enriched the prevailing German style with a robust contrapuntal technique, an unrivalled control of harmonic and motivic organisation, and the adaptation of rhythms, forms and textures from abroad, particularly from Italy and France.

Revered for their intellectual depth, technical command and artistic beauty, Bach's works include the Brandenburg Concertos, the Goldberg Variations, the Partitas, The Well - Tempered Clavier, the Mass in B minor, the St Matthew Passion, the St John Passion, the Magnificat, the Musical Offering, The Art of Fugue, the English and French Suites, the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, the Cello Suites, more than 200 surviving cantatas, and a similar number of organ works, including the famous Toccata and Fugue in D minor and Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, and the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes and Organ Mass. Bach's abilities as an organist were highly respected throughout Europe during his lifetime, although he was not widely recognised as a great composer until a revival of interest and performances of his music in the first half of the 19th century. He is now generally regarded as one of the main composers of the Baroque style, and as one of the greatest composers of all time.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach, Saxe - Eisenach, on 21 March 1685, O.S.31 March 1685, N.S.. He was the youngest child of Johann Ambrosius Bach, the director of the town musicians, and Maria Elisabeth Lämmerhirt. His father taught him to play violin and harpsichord. His uncles were all professional musicians, whose posts ranged from church organists and court chamber musicians to composers. One uncle, Johann Christoph Bach (1645 – 93), introduced him to the art of organ playing. Bach was proud of his family's musical achievements, and around 1735 he drafted a genealogy, "Origin of the musical Bach family".

Bach's mother died in 1694, and his father eight months later. The 10 year old orphan moved in with his oldest brother, Johann Christoph Bach (1671 – 1721), the organist at the Michaeliskirche in Ohrdruf, Saxe - Gotha - Altenburg. There, he copied, studied and performed music, and received valuable teaching from his brother, who instructed him on the clavichord. J.C. Bach exposed him to the works of the great South German composers of the day, such as Johann Pachelbel (under whom Johann Christoph had studied) and Johann Jakob Froberger, to the music of North German composers; to Frenchmen, such as Jean - Baptiste Lully, Louis Marchand, Marin Marais, and to the Italian clavierist Girolamo Frescobaldi. The young Bach probably witnessed and assisted in the maintenance of the organ music. Bach's obituary indicates that he copied music out of Johann Christoph's scores, but his brother had apparently forbidden him to do so, possibly because scores were valuable and private commodities at the time.

At the age of 14, Bach, along with his older school friend George Erdmann, was awarded a choral scholarship to study at the prestigious St. Michael's School in Lüneburg in the Principality of Lüneburg. This involved a long journey with his friend, probably undertaken partly on foot and partly by coach. His two years there appear to have been critical in exposing him to a wider facet of European culture. In addition to singing in the a cappella choir, it is likely that he played the School's three manual organ and its harpsichords. He probably learned French and Italian, and received a thorough grounding in theology, Latin, history, geography, and physics. He would have come into contact with sons of noblemen from northern Germany sent to the highly selective school to prepare for careers in diplomacy, government, and the military.

Although little supporting historical evidence exists at this time, it is almost certain that while in Lüneburg, young Bach would have visited the Johanniskirche (Church of St. John) and heard (and possibly played) the church's famous organ (built in 1549 by Jasper Johannsen and nicknamed the "Böhm organ" after its most prominent master, Georg Böhm). Given his innate musical talent, Bach would have had significant contact with prominent organists of the day in Lüneburg, most notably Böhm (the organist at Johanniskirche) as well as organists in nearby Hamburg, such as Johann Adam Reincken.

In January 1703, shortly after graduating from St. Michael's and after having failed an audition for the post of organist at Sangerhausen, Bach gained an appointment as a court musician in the chapel of Duke Johann Ernst in Weimar. His role there is unclear, but appears to have included menial, non-musical duties. During his seven month tenure at Weimar, his reputation as a keyboard player spread. He was invited to inspect and give the inaugural recital on the new organ at St. Boniface's Church in Arnstadt. The Bach family had close connections with people in this ancient town located about 40 km to the southwest of Weimar. In August 1703, he accepted the post of organist at that church, with light duties, a relatively generous salary, and a fine new organ tuned in the modern tempered system that allowed a wide range of keys to be used. At this time, Bach was embarking on the composition of organ preludes; these works, in the North German tradition of virtuosic, improvisatory preludes, already showed tight motivic control (in which a single, short musical idea is explored throughout a movement). In these works the composer had yet to fully develop his powers of large scale organisation and contrapuntal technique.

Strong family connections and a musically enthusiastic employer failed to prevent tension between the young organist and the authorities after several years in the post. Bach was apparently dissatisfied with the standard of singers in the choir; more seriously, there was his unauthorised absence from Arnstadt for several months in 1705 – 06, when he visited the great organist and composer Dieterich Buxtehude and his Abendmusiken at the Marienkirche in the northern city of Lübeck. The visit to Buxtehude involved a journey on foot of about 400 kilometres (250 mi) each way. The trip reinforced Buxtehude's style as a foundation for Bach's earlier works, and that he overstayed his planned visit by several months suggests that his time with the older master was of great value him. Bach wanted to become amanuensis (assistant and successor) to Buxtehude, but did not want to marry his daughter, which apparently was a condition for his appointment.

According to a record of the proceedings of the Arnstadt consistory in August 1705, Bach was involved in a brawl:

In 1706 Bach was offered a post as organist at St. Blasius's in Mühlhausen, which he took up the following year. It included significantly higher remuneration and improved conditions, as well as a better choir. Four months after arriving at Mühlhausen, Bach married his second cousin, Maria Barbara Bach. Together they would have seven children, four of whom survived to adulthood including — Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach — who became important composers in their own right.

The

church and city government at Mühlhausen agreed to Bach's plan for

an expensive renovation of the organ at St. Blasius's. He, in turn,

wrote an elaborate, festive cantata — Gott ist mein König, BWV 71 —

for the inauguration of the new council in 1708. The council was so

delighted with the piece that they paid handsomely for its publication,

and twice in later years had the composer return to conduct it. After less than a year Bach left Mühlhausen, returning to Weimar this time as organist and concertmaster at

the ducal court. The larger salary given him by Duke Johann Ernst and

the prospect of working with a large, well funded contingent of

professional musicians may have prompted the move.

Bach moved his family into an apartment just five minutes' walk from

the ducal palace. In the following year, their first child was born and

they were joined by Maria Barbara's elder, unmarried sister, who

remained with them to assist in the running of the household until her

death in 1729. Bach's

position in Weimar marked the start of a sustained period of composing

keyboard and orchestral works, in which he had attained the technical

proficiency and confidence to extend the prevailing large scale

structures and to synthesise influences from abroad. From the music of

Italians such as Vivaldi, Corelli and Torelli,

he learned how to write dramatic openings and adopted their sunny

dispositions, dynamic motor - rhythms and decisive harmonic schemes. Bach

absorbed these stylistic aspects in part by transcribing for

harpsichord and organ the concertos of Vivaldi written for various

combinations of strings and winds; a number of these transcribed works

are still concert favourites. Bach was particularly attracted to the

Italian style in which one or more solo instruments alternate

section - by - section with the full orchestra throughout a movement. In

Weimar, Bach continued to play and compose for the organ, and to

perform a varied repertoire of concert music with the duke's ensemble. He also began to write the preludes and fugues which were later assembled into his monumental work Das Wohltemperierte Clavier ("The well - tempered keyboard" — Clavier meaning clavichord or harpischord). It consists of two collections compiled in 1722 and 1744, each containing a prelude and fugue in every major and minor key. During his time at Weimar, Bach started work on the "Little Organ Book" for his eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann; this contains traditional Lutheran chorales (hymn tunes),

set in complex textures to assist the training of organists. The book

illustrates two major themes in Bach's life: his dedication to teaching

and his love of the chorale as a musical form. Bach eventually fell out

of favour in Weimar and was, according to a translation of the court secretary's report, jailed for almost a

month before being unfavourably dismissed: Leopold, Prince of Anhalt - Köthen hired Bach to serve as his Kapellmeister (director of music).

Prince Leopold, himself a musician, appreciated Bach's talents, paid

him well, and gave him considerable latitude in composing and

performing. The prince was Calvinist and did not use elaborate music in his worship; thus, most of Bach's work from this period was secular, including the Orchestral Suites, the Six Suites for Unaccompanied Cello and the Sonatas and partitas for solo violin. The well known Brandenburg Concertos date from this period. Bach composed secular cantatas for the court such as the Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht, BWV 134a. On

7 July 1720, while Bach was abroad with Prince Leopold, Bach's wife

Maria Barbara, the mother of his first seven children, suddenly died.

The following year, the widower met Anna Magdalena Wilcke, a young, highly gifted soprano 17 years his junior, who performed at the court in Köthen; they married on 3 December 1721. Together they had 13 more children, six of whom survived into adulthood: Gottfried Heinrich, Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian,

all of whom became significant musicians; Elisabeth Juliane Friederica

(1726 – 81), who married Bach's pupil Johann Christoph Altnikol; Johanna

Carolina (1737 – 81); and Regina Susanna (1742 – 1809).

In 1723, Bach was appointed Cantor of the

Thomasschule at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, as well as Director of Music in the principal churches in the town. This was a prestigious post in the mercantile city in the Electorate of Saxony,

which he held for 27 years until his death. It brought him into contact

with the political machinations of his employer, the Leipzig Council. The Council comprised two factions: the Absolutists, loyal to the Saxon monarch in Dresden, Augustus the Strong; and the City - Estate faction,

representing the interests of the mercantile class, the guilds and

minor aristocrats. Bach was the nominee of the monarchists, in

particular of the Mayor at the time, Gottlieb Lange, a lawyer who had

earlier served in the Dresden court. In return for agreeing to Bach's

appointment, the City - Estate faction was granted control of the School,

and Bach was required to make a number of compromises with respect to

his working conditions. Although

it appears that no one on the Council doubted Bach's musical genius,

there was continual tension between the Cantor, who regarded himself as

the leader of church music in the city, and the City - Estate faction,

which saw him as a schoolmaster and wanted to reduce the emphasis on

elaborate music in both the School and the Churches. The Council never

honoured Lange's promise at interview of a handsome salary of 1,000 Thaler a

year, although it did provide Bach and his family with a smaller income

and a good apartment at one end of the school building, which was

renovated at great expense in 1732. Bach's post required him to instruct the students of the Thomasschule in singing and to provide weekly music at the two main churches in Leipzig, St. Thomas and St Nicholas.

He was also required to teach Latin, but he was allowed to employ a

deputy to do this instead. In an astonishing burst of creativity, he

wrote up to five annual cantata cycles during his first six years in Leipzig (two of which are lost).

Most of these concerted works expound on the Gospel readings for every

Sunday and feast day in the Lutheran year; many were written using

traditional church hymns, such as Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, and Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern as inspiration for chorale cantatas. To rehearse and perform these works at St. Thomas Church, Bach sat at the harpsichord or stood in front of the choir on the lower gallery at the west end, his back to the congregation and the altar at the east end.

He would have looked upwards to the organ that rose from a loft about

four metres above. To the right of the organ in a side gallery was the

winds, brass and timpani; to the left were the strings. The Council

provided only about eight permanent instrumentalists, a source of

continual friction with the Cantor, who had to recruit the rest of the

20 or so players required for medium - to - large scores from the

University, the School and the public. The organ or harpsichord was

probably played by the composer (when not standing to conduct), the

in-house organist, or one of Bach's elder sons, Wilhelm Friedemann or

Carl Philipp Emanuel. Bach

drew the soprano and alto choristers from the School, and the tenors

and basses from the School and elsewhere in Leipzig. Performing at

weddings and funerals provided extra income for these groups; it was

probably for this purpose, and for in-school training, that he wrote at

least six motets, mostly for double choir. As part of his regular church work, he performed motets of the Venetian School and Germans such as Heinrich Schütz, which would have served as formal models for his own motets. Bach spent much of the 1720s composing cantatas; he then assembled a large repertoire of church music for Leipzig's two main churches. He wanted to broaden his composing and performing beyond the liturgy. In March 1729, he took over the directorship of the Collegium Musicum, a secular performance ensemble that had been started in 1701 by his old friend, the composer Georg Philipp Telemann.

This was one of the dozens of private societies in the major

German speaking cities that had been established by musically active

university students; these societies had come to play an increasingly

important role in public musical life and were typically led by the

most prominent professionals in a city. In the words of Christoph Wolff, assuming the directorship was a shrewd move that 'consolidated Bach's firm grip on Leipzig's principal musical institutions'. During much of the year, Leipzig's Collegium Musicum performed twice weekly for two hours in the Zimmermannsches Caffeehaus, a Coffeehouse on

Catherine Street off the main market square. Many of Bach's works

during the 1730s and 1740s were written for and performed by the

Collegium Musicum; among these were almost certainly parts of the Clavier - Übung (Keyboard Practice) and many of the violin and harpsichord concertos. In 1733, Bach composed the Kyrie and Gloria of the Mass in B minor. He presented the manuscript to the King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania and Elector of Saxony, August III in an eventually successful bid to persuade the monarch to appoint him as Royal Court Composer.

He later extended this work into a full Mass, by adding a Credo,

Sanctus and Agnus Dei, the music for which was almost wholly taken from

some of the best of his cantata movements. Bach's appointment as court

composer appears to have been part of his long term struggle to achieve

greater bargaining power with the Leipzig Council. Although the

complete mass was probably never performed during the composer's

lifetime, it is considered to be among the greatest choral works of all time. Between 1737 and 1739, Bach's former pupil Carl Gotthelf Gerlach took over the directorship of the Collegium Musicum. In 1747, Bach visited the court of the King of Prussia in Potsdam.

There the king played a theme for Bach and challenged him to improvise

a fugue based on his theme. Bach improvised a three part fugue on

Frederick's pianoforte, then a novelty, and later presented the king with a Musical Offering which

consists of fugues, canons and a trio based on the "royal theme,"

nominated by the monarch. Its six part fugue includes a slightly

altered subject more suitable for extensive elaboration. The Art of Fugue was written in Leipzig before Bach's death and was not unfinished. It consists of 18 complex fugues and canons based on a simple theme. It was only published posthumously. The final work Bach completed was a chorale prelude for organ, dictated to his son - in - law, Johann Altnikol, from his deathbed. Entitled Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit (Before thy throne I now appear, BWV 668a);

when the notes on the three staves of the final cadence are counted and

mapped onto the Roman alphabet, the initials "JSB" are found.

Bach's health declined in 1749; on 2 June,

Heinrich von Brühl wrote to one of the Leipzig burgomasters to request that his music director, Gottlob Harrer, fill the post of Thomascantor and Director musices posts "upon the eventual ... decease of Mr. Bach." Bach became increasingly blind, and the British eye surgeon John Taylor operated on Bach while visiting Leipzig in 1750. On

28 July 1750 Bach died at the age of 65. A contemporary newspaper

reported the cause of death as "from the unhappy consequences of the

very unsuccessful eye operation". Some modern historians speculate the cause of death was a stroke complicated by pneumonia. An obituary was written by his son Emanuel and his pupil Johann Friedrich Agricola at the time. Bach's estate was valued at 1159 Thaler and included five Clavecins, two lute-harpsichords, three violins, three violas, two cellos, a viola da gamba, a lute and a spinet, and 52 "sacred books", including books by Martin Luther and Josephus. He

was originally buried at Old St. John's Cemetery in Leipzig. His grave

went unmarked for nearly 150 years. In 1894 his coffin was finally

discovered and reburied in a vault within St. John's Church. This

building was destroyed by Allied bombing during World War II, and in

1950 Bach's remains were taken to their present resting place at

Leipzig's Church of St. Thomas A comprehesive obituary of Bach was published (without attribution) four years later in 1754 by Lorenz Christoph Mizler (another former student) in Musikalische Bibliothek a musical periodical. The obituary remains probably "the richest and most trustworthy" early

source document about Bach. However, after his death, Bach's reputation

as a composer at first declined; his work was regarded as old fashioned

compared to the emerging classical style. Initially he was remembered more as a player, teacher and as the father of his children, most notably Johann Christian and Carl Philipp Emanuel. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, Bach was widely recognised for his keyboard work. Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin were among his most prominent admirers. Beethoven described "Urvater der Harmonie" [Original father of harmony]. Composers such as Mozart, Beethoven, Robert Schumann, and Felix Mendelssohn began writing in a more contrapuntal style after being exposed to Bach's music. The composer's reputation among the wider public was prompted in part by Johann Nikolaus Forkel's 1802 biography. Felix Mendelssohn significantly contributed to the revival of Bach's reputation with his 1829 Berlin performance of the St Matthew Passion. In 1850, the Bach Gesellschaft (Bach

Society) was founded to promote the works; by 1899, the Society had

published a comprehensive edition of the composer's works, with a

conservative approach to editorial intervention. At the time Bach's

music was mostly performed on the newly prominent Hammerklavier. During

the 20th century, the process of recognising the musical as well as the

pedagogic value of some of the works has continued, perhaps most

notably in the promotion of the Cello Suites by Pablo Casals. Another development has been the growth of the "authentic" or period performance movement,

which, as far as possible, attempts to present the music as the

composer intended it. Examples include the playing of keyboard works on

the harpsichord rather than a modern grand piano and the use of small choirs or single voices instead of the larger forces favoured by 19th and early 20th century performers.

Bach's contributions to music — or, to borrow a term popularised by his student Lorenz Christoph Mizler, his "musical science" — are frequently bracketed with those by William Shakespeare in English literature and Isaac Newton in physics.

In Germany, many streets were named and statues were erected in honour

of Bach during the twentieth century. Three pieces by Bach's work were

included onboard the Voyager spacecrafts in the form of golden records that were meant to "represent our hope and our determination and our goodwill".

The

Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod and Episcopal Church of the United States of America commemorate Bach as a musician or composer, on 28 July in their respective Calendars of Saints.