<Back to Index>

- Criminologist Cesare Lombroso, 1835

- Writer Robert Musil, 1880

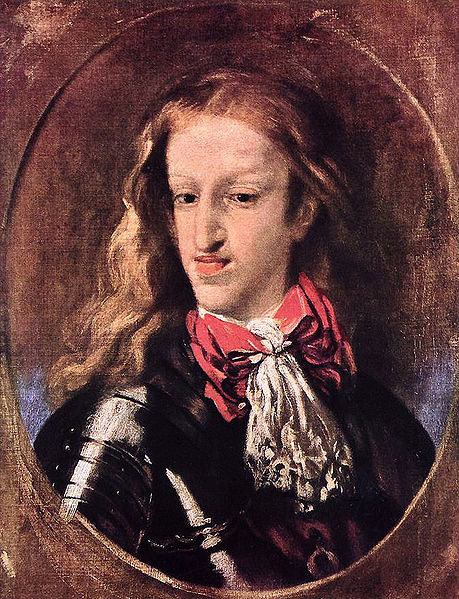

- King of Spain Charles II, 1661

PAGE SPONSOR

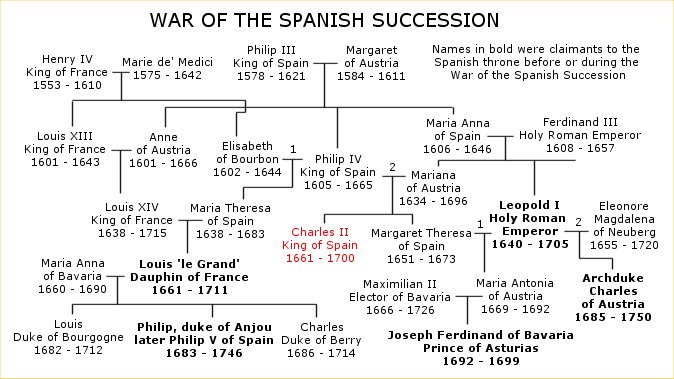

Charles II (6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700) was the last Habsburg King of Spain and the ruler of large parts of Italy, the Spanish territories in the Southern Low Countries, and Spain's overseas Empire, stretching from the Americas to the Spanish East Indies. He is noted for his extensive physical, intellectual, and emotional disabilities — along with his consequent ineffectual rule — as well as his role in the developments preceding the War of the Spanish Succession.

Charles was born in Madrid, the only surviving son of his predecessor, King Philip IV of Spain and his second Queen (and niece), Mariana of Austria, another Habsburg. His birth was greeted with joy by the Spanish, who feared the disputed succession which could have ensued if Philip IV had left no male heir.

17th century European noble culture commonly matched cousin to first cousin and uncle to niece, to preserve a prosperous family's properties. Charles's own immediate pedigree was exceptionally populated with nieces giving birth to children of their uncles: Charles's mother was a niece of Charles's father, being a daughter of Maria Anna of Spain (1606 – 46) and Emperor Ferdinand III. Thus, Empress Maria Anna was simultaneously his aunt and grandmother and Margarita of Austria was both his grandmother and great - grandmother. This inbreeding had given many in the family hereditary weaknesses. That Habsburg generation was more prone to still - births than were peasants in Spanish villages. There was also insanity in Charles's family; his great - great - great (- great - great, depending along which lineage one counts) grandmother, Joanna of Castile ("Joanna the Mad"; however, the degree to which her "madness" was induced by circumstances of her confinement and political intrigues targeting her is debated), mother of the Spanish King Charles I (who was also Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) became insane early in life. Joanna was two of Charles' 16 great - great - great - grandmothers, six of his 32 great - great - great - great - grandmothers, and six of his 64 great - great - great - great - great - grandmothers.

Dating to approximately the year 1550, outbreeding in Charles II's lineage had ceased. From then on, all his ancestors were in one way or another descendants of Joanna the Mad and Philip I of Castile, and among these just the royal houses of Spain, Austria and Bavaria. Charles II's genome was actually more homozygous than that of an average child whose parents are siblings. He was born physically and mentally disabled, and disfigured. Possibly through affliction with mandibular prognathism, he was unable to chew. His tongue was so large that his speech could barely be understood, and he frequently drooled. It has been suggested that he suffered from the endocrine disease acromegaly, or his inbred lineage may have led to a combination of rare genetic disorders such as combined pituitary hormone deficiency and distal renal tubular acidosis.

Consequently, Charles II is known in Spanish history as El Hechizado ("The Hexed") from the popular belief – to which Charles himself subscribed – that his physical and mental disabilities were caused by "sorcery." The king went so far as to be exorcised. Not having learned to speak until the age of four nor to walk until eight, Charles was treated as virtually an infant until he was ten years old. Fearing the frail child would be overtaxed, his caretakers did not force Charles to attend school. The indolence of the young Charles was indulged to such an extent that at times he was not expected to be clean. When his half - brother Don John of Austria, a natural son of Philip IV, obtained power by exiling the queen mother from court, he covered his nose and insisted that the king at least brush his hair. The only vigorous activity in which Charles is known to have participated was shooting. He occasionally indulged in the sport in the preserves of the Escorial.

Born in the capital of the vast Spanish empire, Madrid, and as the only surviving male heir of his father's two marriages (the only brother of Charles to survive infancy was Balthasar Charles, Prince of Asturias, who died at the age of 16 in 1646), he was named the Principe de Asturias as his heir.

When Charles was four, his father died and his mother was made his regent — a position she retained during much of his reign. Though she was exiled by the king's illegitimate half - brother John of Austria the Younger,

she returned to the court after John's death in 1679. The queen mother

managed the country affairs through a series of favourites ("validos"),

whose merits usually amounted to no more than meeting the queen's

fancy. The sheer size of the kingdom at that time made this kind of

government increasingly damaging to the realm's affairs. The

years in which Charles II sat on the throne were difficult for Spain.

The economy was stagnant, there was hunger in the land, and the power

of the monarchy over the various Spanish provinces was extremely weak.

Charles' unfitness for rule meant he was often ignored and power during

his reign became the subject of court intrigues and foreign,

particularly French, and Austrian influence. During the reign of Charles II, the decline of Spanish power and prestige that started in the last years of Count - Duke of Olivares' prime ministership accelerated. Although the peace Treaty of Lisbon with Portugal in 1668 ceded the North African enclave of Ceuta to Spain, it was little solace for the loss of Portugal and the Portuguese colonies by Philip IV to the Duke of Braganza's successful revolt against more than 60 years of Habsburg rule. Charles presided over the greatest auto - da - fé in the history of the Spanish Inquisition in

1680, in which 120 prisoners were forced to participate, of whom 21

were later burnt at the stake. A large, richly adorned book was

published celebrating the event. Toward the end of his life, in one of

his few independent acts as King, Charles created a Junta Magna (Great

Council) to examine and investigate the Spanish Inquisition. The

council's report was so damning of the Inquisition that the Inquisitor

General convinced the decrepit monarch to "consign the 'terrible

indictment' to the flames". When Philip V took the throne, he called for the report but no copy could be found. In 1679, the 18 year old Charles II married Marie Louise d'Orléans (1662 – 1689), eldest daughter of Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (the only sibling of Louis XIV) and his first wife Princess Henrietta of England. At that time, Marie Louise was known as a lovely young woman. It is likely that Charles was impotent, and no children were born. Marie Louise became deeply depressed and died at 26, ten years after their marriage, leaving 28 year old Charles heartbroken. Still in desperate need of a male heir, the next year he married the 23 year old Palatine princess Maria Anna of Neuburg, a daughter of Philip William, Elector of the Palatinate, and sister - in - law of his uncle Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor. However, this marriage was no more successful than the first in producing the much desired heir. Toward

the end of his life Charles became increasingly hypersensitive and

strange, at one point demanding that the bodies of his family be

exhumed so he could look upon the corpses. He died in Madrid in 1700. As the American historians Will and Ariel Durant put it, Charles II was "short, lame, epileptic, senile, and completely bald before 35, he was always on the verge of death, but repeatedly baffled Christendom by continuing to live."

When Charles II died in 1700, the line of the

Spanish Habsburgs died with him. He had named as his successor a grand - nephew, Philip, Duke of Anjou (a grandson of the reigning French king Louis XIV, and of Charles' half - sister, Maria Theresa of Spain —

Louis XIV himself was an heir to the Spanish throne through his mother,

daughter of Philip III). As alternate successor he had named his blood

cousin Charles (from the Austrian branch of the Habsburg dynasty). The specter of the multi - continental empire of Spain passing

under the effective control of Louis XIV provoked a massive coalition

of powers to oppose the Duc d'Anjou's succession. The actions of Louis

heightened the fears of, among others, the English, the Dutch and the

Austrians. In February of 1701, the French King caused the Parlement of Paris (a court) to register a decree that should Louis himself have no heir that the Duc d'Anjou — Phillip V of Spain would surrender the Spanish throne for that of the French, ensuring dynastic continuity in Europe's greatest land power. However,

a second act of the French King "justified a hostile interpretation":

pursuant to a treaty with Spain, Louis occupied several towns in the Spanish Netherlands (modern Belgium and Nord - Pas - de - Calais).

This was the spark that ignited the powder keg created by the

unresolved issues of the War of the League of Augsburg (1689 – 97) and

the acceptance of the Spanish inheritance by Louis XIV for his grandson. Almost immediately the War of the Spanish Succession (1702

– 1713)

began. After eleven years of bloody, global warfare, fought on four

continents and three oceans, the Duc d'Anjou, as Philip V, was

confirmed as King of Spain on substantially the same terms that the

powers of Europe had agreed to before the war. Thus the Treaties of

Utrecht and Rastatt ended the war and "achieved little more than...

diplomacy might have peacefully achieved in 1701." A proviso of

the peace perpetually forbade the union of the Spanish and French

thrones. The House of Bourbon,

founded by Philip V, has intermittently occupied the Spanish throne

ever since, and sits today on the throne of Spain in the person of Juan Carlos I of Spain (1975 – present).