<Back to Index>

- Physicist Johannes "Janne" Robert Rydberg, 1854

- Poet Teofilo Folengo (Merlino Coccajo), 1491

- General of the Imperial Japanese Army Tomoyuki Yamashita (The Tiger of Malaya), 1885

PAGE SPONSOR

General Tomoyuki Yamashita (山下 奉文 Yamashita Tomoyuki, November 8, 1885 – February 23, 1946) was a general of the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. He was most famous for conquering the British colonies of Malaya and Singapore, earning the nickname "The Tiger of Malaya".

Yamashita was born the son of a local doctor in Osugi village, in what is now part of Ōtoyo village, Kōchi prefecture, Shikoku. He attended military preparatory schools in his youth.

After graduating from the 18th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1905, Yamashita joined the Army in 1906 and fought against the German Empire in Shantung, China, in 1914. He attended the 28th class of the Army War College, graduating sixth in his class in 1916. He married Hisako Nagayama, the daughter of retired General Nagayama in 1916. Yamashita became an expert on Germany, serving as assistant military attaché at Bern, Switzerland, and Berlin, Germany, from 1919 – 1922.

On his return to Japan in 1922, Yamashita served in the Imperial Headquarters and the Staff College. While posted to the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff, Yamashita unsuccessfully promoted a military reduction plan. Despite his ability, Yamashita fell into disfavor as a result of his involvement with political factions within the Japanese military. As a leading member of the "Imperial Way" group, he became a rival to Hideki Tōjō and other members of the "Control Faction". In 1928, Yamashita was posted to Vienna, Austria, as the military attaché.

In 1930, Colonel Yamashita was given command of the elite 3rd Imperial Infantry Regiment. After the February 26 Incident of 1936, he fell into disfavor with Emperor Hirohito due to his appeal for leniency toward the rebel officers involved in the attempted coup. Yamashita insisted that Japan should end the conflict with China and keep peaceful relations with the United States and Great Britain, but he was ignored and subsequently assigned to an unimportant post in the Kwantung Army. From 1938 to 1940, he was assigned to command the IJA 4th Division which saw some action in northern China against Chinese insurgents fighting the occupying Japanese armies. In December 1940, Yamashita was sent on a clandestine military mission to Germany and Italy, where he met with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. On 6 November 1941, Yamashita was put in command of the Twenty-Fifth Army. On 8 December, he launched an invasion of Malaya, from bases in French Indochina. In the campaign, which concluded with the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, Yamashita's 30,000 front line soldiers captured 130,000 British, Indian, and Australian troops, the largest surrender of British led personnel in history. He became known as the "Tiger of Malaya". The campaign and the subsequent Japanese occupation of Singapore included war crimes committed against captive Allied personnel and civilians, such as the Alexandra Hospital and Sook Ching massacres.

Yamashita's culpability for these events remains a matter of

controversy, as some argued that he had failed to prevent them.

However, Yamashita had the officer who instigated the hospital massacre

and some soldiers caught looting executed for these acts, and he personally apologized to the surviving Alexandra Hospital patients.

On 17 July 1942, Yamashita was reassigned from Singapore to far away

Manchukuo, again having been given a post in commanding the Japanese First Army, and was effectively sidelined for a major part of the Pacific War. It is thought that Tōjō, by then the Prime Minister, was responsible for his banishment, taking advantage of Yamashita's gaffe during a speech made to Singaporean civilian leaders in early 1942, when he referred to the local populace as "citizens of the Empire of Japan" (this was considered embarrassing for the Japanese government, who officially did not consider the residents of occupied territories to have the rights or privileges of Japanese citizenship). In

1944, when the war situation was critical for Japan, Yamashita was

rescued from his enforced exile in China by the new Japanese government

after the downfall of Hideki Tōjō and his cabinet, and he assumed the

command of the Fourteenth Area Army to defend the Philippines on 10 October. The U.S. forces landed on Leyte on 20 October, only ten days after Yamashita's arrival at Manila. On 6 January 1945, the Sixth U.S. Army, totalling 200,000 men, landed at Lingayen Gulf in Luzon. Yamashita

commanded approximately 262,000 troops in three defensive groups; the

largest, the Shobo Group, under his personal command numbered 152,000

troops, which defended northern Luzon. The smallest group, totaling

30,000 troops, known as the Kembu Group, under the command of Tsukada,

which defended Bataan and the western shores. The last group, the Shimbu Group, totaling 80,000 men under the command of Yokoyama, defended Manila and southern Luzon. Yamashita tried to rebuild his army but was forced to retreat from Manila to the Sierra Madre mountains of northern Luzon, as well as the Cordillera Central mountains. Yamashita ordered all troops, except those tasked with security, out of the city. Almost immediately, Imperial Japanese Navy Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi re-occupied

Manila with 16,000 sailors, with the intent of destroying all port

facilities and naval storehouses. Once there, Iwabuchi took command of

the 3,750 Army security troops, and against Yamashita's specific order, turned the city into a battlefield. The battle and the Japanese atrocities resulted in the deaths of more than 100,000 Filipino civilians, in what would be later known as the Manila massacre, during the fierce street fighting for the capital which raged from February 4 to March 3. Yamashita used delaying tactics to maintain his army in Kiangan (part of the Ifugao Province), until 2 September 1945, after the surrender of Japan,

where his forces were reduced to under 50,000 by the tough campaigning

by elements of the combined American and Filipino soldiers including the recognized guerrillas. Yamashita surrendered in the presence of Generals Jonathan Wainwright and Arthur Percival, both of whom had been prisoners of war in Manchuria.

Ironically, Percival had surrendered to Yamashita after the Battle of

Singapore. This time, however, Percival refused to shake Yamashita's

hand, being angered by the exterminationist tactics that Yamashita had

allegedly employed against Allied POWs, so Yamashita burst into tears.

Although Yamashita might have been expected to commit suicide prior

to this surrender, he reportedly explained his decision not to kill

himself by saying that if he did "someone else will have to take the

blame."

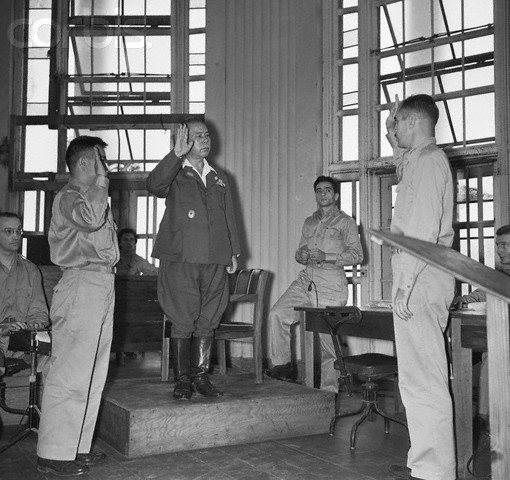

From 29 October to 7 December 1945, an American

military tribunal in Manila tried General Yamashita for war crimes relating to the Manila Massacre and many atrocities in the Philippines and Singapore against civilians and prisoners of war, such as the Sook Ching massacre, and sentenced him to death. This controversial case has become a precedent regarding the command responsibility for war crimes and is known as the Yamashita Standard. The

trial was not without criticism. The commission of five officers lacked

combat experience and formal legal training, and the defense counsel

complained they were given insufficient time in which to prepare their

case. With many Filipinos perhaps

understandably anxious to make Yamashita pay for their sufferings

during the Japanese occupation, the intensely emotional atmosphere of

the trial rendered it extremely difficult for the court to judge the

case objectively. The court admitted hearsay evidence, unnamed witnesses, and other forms of evidence which the defense could not reasonably challenge. Because the well known Yamashita was the first Japanese to be tried by the Allies for war crimes, MacArthur wanted a swift trial and a guilty verdict to establish a precedent for the approaching trials in Tokyo and elsewhere in the Far East. In dissenting from the Supreme Court of the United States's majority, Justice W.B. Rutledge wrote: The

principal accusation against Yamashita was that he had failed in his

duty as commander of Japanese forces in the Philippines to prevent them

from committing brutal atrocities. The defense acknowledged that

atrocities had been committed but contended that the breakdown of

communications and the Japanese chain of command in the chaotic battle

of the second Philippines campaign was such that Yamashita could not

have controlled his troops even if he had known of their actions, which

was not certain in any case. Furthermore, many of the atrocities had

been committed by Japanese naval forces outside his command. During

his trial, the defense attorneys who challenged Douglas MacArthur

deeply impressed General Yamashita with their dedication to the case,

and reaffirmed his respect for his former enemies. American lawyer

Harry E. Clarke, Sr., then a U.S. Army colonel, served as chief counsel for the defense. In his opening statement, Clarke asserted: The

court found Yamashita guilty as charged and sentenced him to death.

Clarke appealed the sentence to MacArthur, who upheld it. He then

appealed to the Philippines Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court, both of which declined to review the verdict. The legitimacy of the hasty trial was questioned by many at the time, including Justice Frank Murphy,

who protested various procedural issues, the inclusion of hearsay

evidence, and the general lack of professional conduct by the

prosecuting officers. In re Yamashita 327 U.S. 1, 27 (1946). The

considerable body of evidence that Yamashita did not have ultimate

command responsibility over all military units in the Philippines was

not admitted in court.

Following the Supreme Court decision, an appeal for clemency was made to

U.S. President Harry S. Truman;

Truman, however, declined to intervene and left the matter entirely in

the hands of the military authorities. In due course, General MacArthur

confirmed the sentence of the Commission. On 23 February 1946, at Los Baños, Laguna Prison

Camp, 30 miles (48 km) south of Manila, Yamashita was hanged.

After climbing the thirteen steps leading to the gallows, he was asked

if he had a final statement. To this Yamashita replied through a

translator: Yamashita's chief of staff in the Philippines, Akira Mutō, was executed on 23 December 1948 after having been found guilty of war crimes by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

“ More

is at stake than General Yamashita's fate. There could be no possible

sympathy for him if he is guilty of the atrocities for which his death

is sought. But there can be and should be justice administered

according to the law... It is not too early, it is never too early, for

the nation steadfastly to follow its great constitutional traditions,

none older or more universally protective against unbridled power than

due process of law in the trial and punishment of men, that is, of all

men, whether citizens, aliens, alien enemies or enemy belligerents. ” “ The

Accused is not charged with having done something or having failed to

do something, but solely with having been something…. American

jurisprudence recognizes no such principle so far as its own military

personnel are concerned…. No one would even suggest that the Commanding

General of an American occupational force becomes a criminal every time

an American soldier violates the law… one man is not held to answer for

the crime of another. ” “ As

I said in the Manila Supreme Court that I have done with my all

capacity, so I don't ashame in front of the gods for what I have done

when I have died. But if you say to me 'you do not have any ability to

command the Japanese Army' I should say nothing for it, because it is

my own nature. Now, our war criminal trial going on in Manila Supreme

Court, so I wish to be justify under your kindness and right. I know

that all your American and American military affairs always has

tolerant and rightful judgment. When I have been investigated in Manila

court I have had a good treatment, kindful attitude from your good

natured officers who all the time protect me. I never forget for what

they have done for me even if I had died. I don't blame my executioner.

I'll pray the gods bless them. Please send my thankful word to Col.

Clarke and Lt. Col. Feldhaus, Lt. Col. Hendrix, Maj. Guy, Capt.

Sandburg, Capt. Reel, at Manila court, and Col. Arnard. I thank you. ”