<Back to Index>

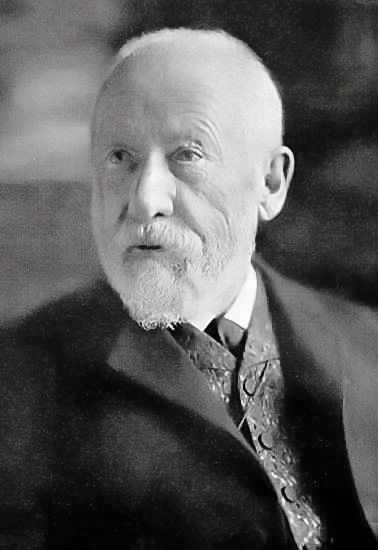

- Philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey, 1833

- Painter Emile Wauters, 1846

- Diplomat Ferdinand Marie, Vicomte de Lesseps, 1805

PAGE SPONSOR

Wilhelm Dilthey (19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist and hermeneutic philosopher, who held Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, working in a modern research university, Dilthey's research interests revolved around questions of scientific methodology, historical evidence and history's status as a science. He could be considered an empiricist, in contrast to the idealism prevalent in Germany at the time, but his account of what constitutes the empirical and experiential differs from British empiricism and positivism in its central epistemological and ontological assumptions, which are drawn from German literary and philosophical traditions.

Dilthey was born in 1833 in the Rhineland village of Biebrich, now in Hesse, Germany. As a young man he followed family traditions by studying theology in Heidelberg, where his teachers included the young Kuno Fischer. He then moved to the University of Berlin and was taught by, amongst others, Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg and August Boeckh, both former pupils of Friedrich Schleiermacher. He edited Schleiermacher's letters and was also commissioned to write a biography. In 1867 he took up a professorship in Basel, but later returned to Berlin where he held the prestigious chair in philosophy at the University of Berlin. He died in 1911.

Dilthey was inspired in part by the works of Friedrich Schleiermacher on hermeneutics, which he helped revive. Both figures are linked to German Romanticism. The school of Romantic hermeneutics stressed that historically embedded interpreters — a "living" rather than a Cartesian or "theoretical" subject — use 'understanding' and 'interpretation', which combine individual - psychological and social - historical description and analysis, to gain a greater knowledge of texts and authors in their contexts.

The process of interpretive inquiry established by Schleiermacher involved what Dilthey called "the Hermeneutic circle," which is the recurring movement between the implicit and the explicit, the particular and the whole. The "general hermeneutics" that Schleiermacher proposed was a combination of the hermeneutics used to interpret Sacred Scriptures (e.g. the Pauline epistles) and the hermeneutics used by Classicists (e.g. Plato's philosophy). Dilthey saw its relevance for the human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften) in contrast with the natural sciences.

Along with Friedrich Nietzsche, Georg Simmel and Henri Bergson, Dilthey's work influenced early twentieth century "Lebensphilosophie" and "Existenzphilosophie."

Dilthey informed the early Martin Heidegger's approach to hermeneutics in his early lecture courses, in which he developed a "hermeneutics of factical life", and in Being and Time. Heidegger grew increasingly more critical of Dilthey, arguing for a more radical 'temporalization' of the possibilities of interpretation and human existence.

In Wahrheit und Methode (Truth and Method), Hans - Georg Gadamer,

influenced by Heidegger, criticised Dilthey's approach to hermeneutics

as both overly aesthetic and subjective as well as method oriented and

"positivistic." According to Gadamer, Dilthey's hermeneutics is

insufficiently concerned with the ontological event of truth and

inadequately considers the implications of how the interpreter and the

interpreter's interpretations are not outside of tradition but occupy a

particular position within it, i.e., have a temporal horizon. Dilthey was very interested in what we would call sociology today, although he strongly objected to being labelled as such as the sociology of his time was mainly that of Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. He objected to their dialectical / evolutionist assumptions about the necessary changes that all societal formations must go

through, as well as their narrowly natural - scientific methodology. Comte's idea of positivism was, according to Dilthey, one-sided and misleading. Dilthey did, however, have good things to say about the neo-Kantian sociology of Georg Simmel, with whom he was a colleague at the University of Berlin. Simmel himself was later an associate of Max Weber, the primary founder of sociological antipositivism.

J.I. Hans Bakker has argued that Dilthey should be considered one of

the classical sociological theorists due to his own influence in the

foundation of nonpositivist "verstehende" sociology and the "verstehen" method. Jürgen Habermas was also influenced by Dilthey, most notably in the Positivismusstreit of the early 1960s and his early work Knowledge and Human Interests (1968). A

life long concern was to establish a proper theoretical and

methodological foundation for the "human sciences" (e.g. history, law,

literary criticism), distinct from, but equally "scientific" as, the

"natural sciences" (e.g. physics, chemistry). He suggested that all

human experience divides naturally into two parts: that of the

surrounding natural world, in which "objective necessity" rules, and

that of inner experience, characterized by "sovereignty of the will,

responsibility for actions, a capacity to subject everything to

thinking and to resist everything within the fortress of freedom of

his/her own person". Dilthey strongly rejected using a model formed exclusively from the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften), and instead proposed developing a separate model for the human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften).

His argument centered around the idea that in the natural sciences we

seek to explain phenomena in terms of cause and effect, or the general

and the particular; in contrast, in the human sciences, we seek to understand in

terms of the relations of the part and the whole. In the social

sciences we may also combine the two approaches, a point stressed by

German sociologist Max Weber. His principles, a general theory of understanding or comprehension (Verstehen)

could, he asserted, be applied to all manner of interpretation ranging

from ancient texts to art work, religious works, and even law. His

interpretation of different theories of aesthetics in

the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries was preliminary

to his speculations concerning the form aesthetic theory would take in

the twentieth century. Both the natural and human sciences originate in the context or "nexus of life" (Lebenszusammenhang), a concept which influenced the phenomenological account of the lifeworld (Lebenswelt),

but are differentiated in how they relate to their life - context.

Whereas the natural sciences abstract away from it, it becomes the

primary object of inquiry in the human sciences. Dilthey defended his use of the term Geisteswissenschaft (literally,

"spiritual science") by pointing out that other terms such as "social

science" and "cultural sciences" are equally one-sided and that the

human spirit is the central phenomenon from which all others are

derived and analyzable. For Dilthey, like Hegel, "spirit" (Geist)

has a cultural rather than an social meaning. It is not an abstract

intellectual principle or disembodied behavioral experience but refers

to the individual's life in its concrete cultural - historical context.

The very term "Spirit" lifts Dilthey's discussion beyond the

philosophical premisses of pragmatism, instrumentalism and modern days

postmodernism. Dilthey developed a typology of the three basic Weltanschauungen,

or World - Views, which he considered to be "typical" (comparable to Max

Weber's notion of "ideal types") and conflicting ways of conceiving of

man's relation to Nature. This approach influenced Karl Jaspers' Psychology of Worldviews as well as Rudolf Steiner.

Dilthey's ideas should be examined in terms of his similarities and differences with

Wilhelm Windelband and Heinrich Rickert, members of the Baden School of Neo-Kantianism.

Dilthey was not a Neo-Kantian, but had a profound knowledge of Immanuel

Kant's philosophy, which deeply influenced his thinking. But whereas

Neo-Kantianism was primarily interested in epistemology on the basis of

Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, Dilthey took Kant's Critique of Judgment as

his point of departure. An important debate between Dilthey and the

Neo-Kantians concerned the "human" as opposed to "cultural" sciences,

with the Neo-Kantians arguing for the exclusion of psychology from the

cultural sciences and Dilthey for its inclusion as a human science.