<Back to Index>

- Neurophysiologist Charles Scott Sherrington, 1857

- Composer Julius Benedict, 1804

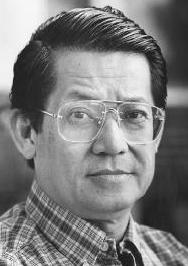

- Senator of the Philippines Benigno Simeon "Ninoy" Aquino, Jr., 1932

PAGE SPONSOR

Benigno Simeon "Ninoy" Aquino, Jr. (November 27, 1932 – August 21, 1983) was a Filipino Senator, Governor of Tarlac, and an opposition leader against President Ferdinand Marcos. He was assassinated at the Manila International Airport (later renamed in his honor) upon returning home from exile in the United States. His death catapulted his widow, Corazon Aquino, to the limelight and subsequently to the presidency, replacing the 20 year Marcos presidency. In 2004, the anniversary of his death was proclaimed as a national holiday now known as Ninoy Aquino Day.

Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. was born in Concepcion, Tarlac, to a prosperous family of hacenderos (landlords), original owners of Hacienda Tinang, Hacienda Lawang and Hacienda Murcia. His grandfather, Servillano Aquino, was a general in the revolutionary army of Emilio Aguinaldo. His father, Benigno S. Aquino, Sr. (1894 – 1947) was a prominent member of the World War II Japanese collaborationist government of Jose P. Laurel, as Vice - President. In fact, his father once occupied the Arlegui Mansion guest house, originally owned by the Spanish - Filipino Laperal family of Manila and Baguio, the same house that his wife Cory Aquino used as private quarters during her presidency and the same house his son Noynoy Aquino candidly refused for having 'too many memories.' His father was one of two politicians representing Tarlac during his lifetime. The other was Jose Cojuangco, father of his future wife. His mother was Doña Aurora Aquino - Aquino (who was also his father's third cousin). His father died while "Ninoy" was in his teens prior to coming to trial on treason charges resulting from his collaboration with the Japanese during the occupation.

Aquino was educated in private schools — St. Joseph's College, Ateneo de Manila, National University, and De La Salle College. He finished high school at San Beda College. Aquino took his tertiary education at the Ateneo de Manila to obtain a Bachelor of Arts degree, but he interrupted his studies. According to one of his biographies, he considered himself to be an average student; his grade was not in the line of 90's nor did it fall into the 70's. At age 17, he was the youngest war correspondent to cover the Korean War for the newspaper The Manila Times of Joaquin "Chino" Roces. Because of his journalistic feats, he received the Philippine Legion of Honor award from President Elpidio Quirino at age 18. At 21, he became a close adviser to then defense secretary Ramon Magsaysay. Ninoy took up law at the University of the Philippines, where he became a member of the Upsilon Sigma Phi, the same fraternity of Ferdinand Marcos. He interrupted his studies again however to pursue a career in journalism. According to Maximo Soliven, Aquino "later 'explained' that he had decided to go to as many schools as possible, so that he could make as many new friends as possible." In early 1954, he was appointed by President Ramon Magsaysay, his wedding sponsor to his 1953 wedding at the Our Lady of Sorrows church in Pasay with Corazon Cojuangco, to act as personal emissary to Luis Taruc, leader of the Hukbalahap rebel group. After four months of negotiations, he was credited for Taruc's unconditional surrender.

He became mayor of Concepcion in 1955 at the age of 22. Aquino

gained an early familiarity with Philippine politics, as he was born

into one of the Philippines' prominent oligarchic clans. His

grandfather served under President Aguinaldo, while his father held

office under Presidents Quezon and Jose P. Laurel. As a consequence, Aquino was able to be elected mayor when he was 22 years

old. Five years later, he was elected the nation's youngest

vice - governor at 27, despite having no real executive experience. Two

years later he became governor of Tarlac province in 1961 at age 29,

then secretary - general of the Liberal Party in 1966. In 1967 he became the youngest elected senator in the country's history at age 34. In

1968, during his first year as senator, Aquino alleged that Marcos was

on the road to establishing "a garrison state" by "ballooning the armed

forces budget", saddling the defense establishment with "overstaying

generals" and "militarizing our civilian government offices" — all these

caveats were uttered barely four years before martial law, as was

typical of the accusatory style of political confrontation at the time.

However, no evidence was ever produced for any of these statements. Aquino

became known as a constant critic of the Marcos regime, as his

flamboyant rhetoric had made him a darling of the media. His most

polemical speech, "A Pantheon for Imelda", was delivered on February

10, 1969. He assailed the Cultural Center, the first project of First

Lady Imelda Marcos as

extravagant, and dubbed it "a monument to shame" and labelled its

designer "a megalomaniac, with a penchant to captivate". By the end of

the day, the country's broadsheets had blared that he labelled the

President's wife, his cousin Paz's former ward, and a woman he had once

courted, "the Philippines' Eva Peron".

President Marcos is said to have been outraged and labelled Aquino "a

congenital liar". The First Lady's friends angrily accused Aquino of

being "ungallant". These so-called "fiscalization" tactics of Aquino

quickly became his trademark in the Senate. It was not until the Plaza Miranda bombing however — on

August 21, 1971 (12 years to the day before Ninoy Aquino's own

assassination) — that the pattern of direct confrontation between Marcos

and Aquino emerged. At 9:15 p.m., at the kick-off rally of the Liberal

Party, the candidates had formed a line on a makeshift platform and

were raising their hands as the crowd applauded. The band played, a

fireworks display drew all eyes, when suddenly there were two loud

explosions that obviously were not part of the show. In an instant the

stage became a scene of wild carnage. The police later discovered two

fragmentation grenades that had been thrown at the stage by "unknown

persons". Eight people died, and 120 others were wounded, many

critically. Aquino was absent when the incident occurred. Although

suspicions pointed to the Nacionalistas (the political party of

Marcos), Marcos allies sought to deflect this by insinuating that,

perhaps, Aquino might have had a hand in the blast in a bid to

eliminate his potential rivals within the party. Later, the Marcos

government presented "evidence" of the bombings as well as an alleged

threat of a communist insurgency, suggesting that the bombings were the

handiwork of the growing New People's Army. Marcos made this a pretext to suspend the right of habeas corpus, vowed that the killers would be apprehended within 48 hours, and arrested a score of known "Maoists" on general principle. Ironically, the police captured one of the

bombers, who was identified as a sergeant of the firearms and explosive

section of the Philippine Constabulary,

a military arm of the government. According to Aquino, this man was

later snatched from police custody by military personnel and never seen

again. President

Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972 and he went on air to

broadcast his declaration on midnight of September 23. Aquino was one

of the first to be arrested and imprisoned on trumped-up charges of

murder, illegal possession of firearms and subversion. He was tried

before Military Commission No. 2 headed by Major General Jose Syjuco.

On April 4, 1975, Aquino announced that he was going on a hunger

strike, a fast to the death to protest the injustices of his military

trial. Ten days through his hunger strike, he instructed his lawyers to

withdraw all motions he had submitted to the Supreme Court. As weeks

went by, he subsisted solely on salt tablets, sodium bicarbonate, amino

acids, and two glasses of water a day. Even as he grew weaker,

suffering from chills and cramps, soldiers forcibly dragged him to the

military tribunal's session. His family and hundreds of friends and

supporters heard Mass nightly at the Santuario de San Jose in Greenhills, San Juan,

praying for his survival. Near the end, Aquino's weight had dropped

from 54 to 36 kilos. Aquino nonetheless was able to walk throughout his

ordeal. On May 13, 1975, on the 40th day, his family and several

priests and friends, begged him to end his fast, pointing out that even

Christ fasted only for 40 days. He acquiesced, confident that he had

made a symbolic gesture. But he remained in prison, and the trial

continued, drawn out for several years. On November 25, 1977, the

Commission found Aquino guilty of all charges and sentenced him to

death by firing squad. In

1978, from his prison cell, he was allowed to take part in the

elections for Interim Batasang Pambansa (Parliament). Although his

friends, former Senators Gerry Roxas and Jovito Salonga, preferred to boycott the elections, Aquino urged his supporters to organize and run 21 candidates in Metro Manila. Thus his political party, dubbed Lakas ng Bayan ("People's Power"), was born. The party's acronym was "LABAN" (in Tagalog). He was allowed one television interview on Face the Nation (hosted

by Ronnie Nathanielsz) and proved to a startled and impressed populace

that imprisonment had neither dulled his rapier like tongue nor

dampened his fighting spirit. Foreign correspondents and diplomats

asked what would happen to the LABAN ticket. People agreed with him

that his party would win overwhelmingly in an honest election. Not

surprisingly, all his candidates lost due to widespread election fraud. In mid March 1980, Aquino suffered a heart attack, possibly the result of seven years in prison, mostly in a solitary cell. He was transported to the Philippine Heart Center, where he suffered a second heart attack. ECG and other tests showed that he had a blocked artery. Philippine surgeons were reluctant to do a coronary bypass,

because it could involve them in a controversy. In addition, Aquino

refused to submit himself to Philippine doctors, fearing possible

Marcos "duplicity"; he preferred to go to the United States for the

procedure or return to his cell at Fort Bonifacio and die. He also

appeared in the 700 Club television ministry of Pat Robertson,

where he narrated his spiritual life, accepted "Christ as his Lord and

Savior" and became a born again Christian, which sprang from a

conversation with Charles Colson, founder of Prison Fellowship, who was involved in the Watergate Scandal during U.S. President Richard Nixon's administration. On May 8, 1980, Imelda Marcos made

an unannounced visit to Aquino at his hospital room. She asked him if

he would like to leave that evening for the U.S., but not before

agreeing on two conditions: 1) that if he left, he would return; 2)

while in the U.S., he would not speak out against the Marcos regime.

She then ordered General Fabian Ver and

Mel Mathay to provide passports and plane tickets for the Aquino

family. Aquino was placed in a closed van, rushed to his home on Times

Street to pack, driven to the airport and put on a plane bound for the

U.S. that same day, accompanied by his family. Aquino was operated on at a hospital in Dallas, Texas. He made a quick recovery, was walking within two weeks and making plans to fly to Damascus, Syria, to meet with Muslim leaders,

which he did five weeks later. When he reiterated that he was returning

to the Philippines, he received a surreptitious message from the Marcos

government saying that he was now granted an extension of his "medical

furlough". Eventually, Aquino decided to renounce his two covenants with Malacañang "because of the dictates of higher national interest". After all, Aquino added, "a pact with the devil is no pact at all". Aquino spent three years in self - exile, living with his family in Newton, a suburb of Boston, Massachusetts. On fellowship grants from Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

he worked on the manuscripts of two books and gave a series of lectures

in school halls, classrooms and auditoriums. He traveled extensively in

the U.S., delivering speeches critical of the Marcos Throughout

his years of expatriation, Aquino was always aware that his life in the

U.S. was temporary. He never stopped affirming his eventual return even

as he enjoyed American hospitality and a peaceful life with his family

on American soil. After spending 7 years and 7 months in prison,

Aquino's finances were in ruins. Making up for the lost time as the

family's breadwinner, he toured America; attending symposiums,

lectures, and giving speeches in freedom rallies opposing the Marcos dictatorship. The most memorable was held at the Wilshire Ebell Theater in Los Angeles, California, on February 15, 1981. In

the first quarter of 1983, Aquino received news about the deteriorating

political situation in his country and the rumored declining health of

President Marcos (due to lupus).

He believed that it was expedient for him to speak to Marcos and

present to him his rationale for the country's return to democracy,

before extremists took over and made such a change impossible.

Moreover, his years of absence made his allies worry that the Filipinos

might have resigned themselves to Marcos' strongman rule and that

without his leadership the centrist opposition would die a natural

death. Aquino

decided to go back to the Philippines, fully aware of the dangers that

awaited him. Warned that he would either be imprisoned or killed,

Aquino answered, "if it's my fate to die by an assassin's bullet, so be

it. But I cannot be petrified by inaction, or fear of assassination,

and therefore stay on the side..." His family, however, learned from a Philippine Consulate official that there were orders from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs not to issue

any passports for them. At that time, their visas had expired and their

renewal had been denied. They therefore formulated a plan for Ninoy to

fly alone (to attract less attention), with the rest of the family to

follow him after two weeks. Despite the government's ban on issuing him

a passport, Aquino acquired one with the help of Rashid Lucman, a former Mindanao legislator and founder of the Bangsamoro Liberation Front, a Moro separatist group against Marcos. It carried the alias Marcial Bonifacio (Marcial for martial law and Bonifacio for Fort Bonifacio, his erstwhile prison). He

eventually obtained a legitimate passport from a sympathizer working in

a Philippine consulate through the help of Roque R. Ablan Jr, then a

Congressman. The Marcos government warned all international airlines

that they would be denied landing rights and forced to return if they

tried to fly Ninoy to the Philippines. Aquino insisted that it was his

natural right as a citizen to come back to his homeland, and that no

government could prevent him from doing so. He left Logan International Airport on August 13, 1983, took a circuitous route home from Boston, via Los Angeles to Singapore. In Singapore, then Tunku Ibrahim Ismail of Johor met Aquino upon his arrival in Singapore and later brought him to Johor to meet with other Malaysian leaders. Once in Johor, Aquino met up with Tunku Ibrahim's father, Sultan Iskandar, who was a close friend to Aquino. He then left for Hong Kong and on to Taipei. He had chosen Taipei as the final stopover when he learned the Philippines had severed diplomatic ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan).

This made him feel more secure; the Taiwan authorities could pretend

they were not aware of his presence. There would also be a couple of

Taiwanese friends accompanying him. From Taipei he flew to Manila on China Airlines Flight 811. Marcos

wanted Aquino to stay out of politics, however Ninoy asserted his

willingness to suffer the consequences declaring, "the Filipino is

worth dying for." He

wished to express an earnest plea for Marcos to step down, for a

peaceful regime change and a return to democratic institutions.

Anticipating the worst, at an interview in his suite at the Taipei Grand Hotel, he revealed that he would be wearing a bullet proof vest,

but he also said that "it's only good for the body, but for the head

there's nothing else we can do." Sensing his own doom, he told the

journalists accompanying him on the flight, "You have to be ready with

your hand camera because this action can become very fast. In a matter

of 3 or 4 minutes it could be all over, and I may not be able to talk

to you again after this." In

his last formal statement that he wasn't able to deliver, he said, "I

have returned to join the ranks of those struggling to restore our

rights and freedom through violence. I seek no confrontation." Aquino

was assassinated on August 21, 1983 when he was shot in the head after

returning to the country. At the time, bodyguards were assigned to him

by the Marcos government. A subsequent investigation produced

controversy but no definitive results. After the Marcos government was

overthrown, another investigation found sixteen defendants guilty. They

were all sentenced to life in prison. Over the years, some were

released, and the last one was freed in March 2009. Another

man on the plane, Rolando Galman, was shot dead on-board shortly after

Aquino was killed. The Marcos government claimed Galman was the

triggerman in Aquino's assassination, but evidence suggests this was

not the case. Aquino's

body lay in state in a glass coffin. No effort was made to disguise a

bullet wound that had disfigured his face. In an interview with

Aquino's mother, Aurora, she told the funeral parlor not to apply

makeup nor embalm her

son, to see "what they did to my son". Thousands of supporters flocked

to see the bloodied body of Aquino, which took place at the Aquino

household in Times St., Quezon City for nine days. Ninoy's wife, Corazon Aquino, and children Ballsy, Pinky, Viel, Noynoy and Kris arrived

the day after the assassination. Aquino's funeral procession on August

31 lasted from 9 a.m., when his funeral mass was held at Santo

Domingo Church in Santa Mesa Heights, Quezon City, with the Cardinal Archbishop of Manila, Jaime Sin officiating, to 9 p.m., when his body was interred at the Manila Memorial Park. More than two million people lined the streets during the procession which was aired by the Church sponsored Radio Veritas, the only station to do so. The procession reached Rizal Park, where the Philippine flag was brought to half-staff. Jovito Salonga, then head of the Liberal Party, said about Ninoy: "...

Ninoy was getting impatient in Boston, he felt isolated by the flow of

events in the Philippines. In early 1983, Marcos was seriously ailing,

the Philippine economy was just as rapidly declining, and insurgency

was becoming a serious problem. Ninoy thought that by coming home he

might be able to persuade Marcos to restore democracy and somehow

revitalize the Liberal Party ..." and called him:

In

Senator Aquino's honor, the Manila International Airport (MIA) where he

was assassinated was renamed Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA)

and his image is printed on the

500 peso bill. August 21, the anniversary of his death, is "Ninoy Aquino Day", an annual public holiday in the Philippines. Several monuments were built in his honor. Most renowned is the bronze memorial in Makati City near the Philippine Stock Exchange,

which today is a venue of endless anti - government rallies and large

demonstrations. Another one bronze statue is in front of the Municipal

Building of Concepcion, Tarlac. Although

Aquino was recognized as the most prominent and most dynamic opposition

leader of his generation, in the years prior to martial law he was

regarded by many as being a representative of the entrenched familial

elite which to this day dominates Philippine politics. While atypically

telegenic and uncommonly articulate, he had his share of detractors and

was not known to be immune to ambitions and excesses of the ruling

political class. However, during his seven years and seven months

imprisoned as a political prisoner of Marcos, Aquino read the book Born Again by convicted Watergate conspirator Charles Colson and it inspired him to a religious awakening. As

a result, the remainder of his personal and political life had a

distinct spiritual sheen. He emerged as a contemporary counterpart of

the great Jose Rizal,

who was among the world's earliest proponents of the use of

non-violence to combat a repressive regime. Some remained skeptical of

Aquino's redirected spiritual focus, but it ultimately had an effect on

his wife's political career. While some may question the prominence

given Aquino in Philippine history, it was his assassination that was

pivotal to the downfall of a despotic ruler and the eventual

restoration of democracy in the Philippines. On October 12, 1954, he married Corazon "Cory" Cojuangco, with whom he had five children (four daughters and a son).