<Back to Index>

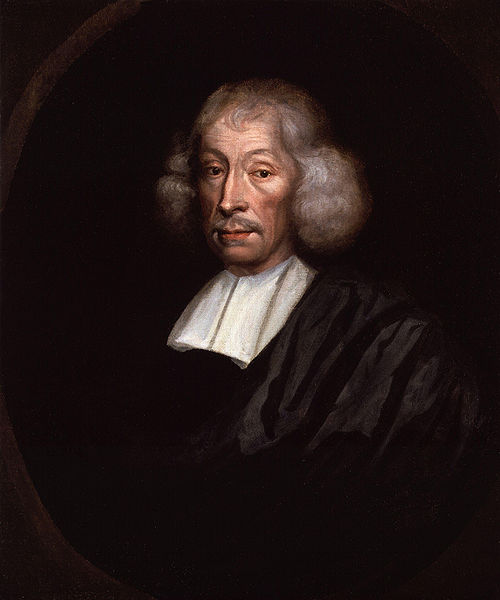

- Naturalist John Ray, 1627

- Sculptor Guillaume Coustou the Elder, 1677

- 19th President of Liberia William Vacanarat Shadrach Tubman, 1895

PAGE SPONSOR

John Ray (29 November 1627 – 17 January 1705) was an English naturalist, sometimes referred to as the father of English natural history. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after "having ascertained that such had been the practice of his family before him".

He published important works on botany, zoology, and natural theology. His classification of plants in his Historia Plantarum, was an important step towards modern taxonomy. Ray rejected the system of dichotomous division by which species were classified according to a pre-conceived, either/or type system, and instead classified plants according to similarities and differences that emerged from observation. Thus he advanced scientific empiricism against the deductive rationalism of the scholastics. He was the first to give a biological definition of the term species.

John Ray was born in the village of

Black Notley.

He is said to have been born in the smithy, his father having been the

village blacksmith. He was sent at the age of sixteen to Cambridge

University: studying at Trinity College and Catharine Hall. His tutor at Trinity was James Duport, and his intimate friend and fellow pupil the celebrated Isaac Barrow. Ray was chosen minor fellow of Trinity in 1649, and later major fellow. He held many college offices, becoming successively lecturer in Greek (1651), mathematics (1653) and humanity (1655), praelector (1657),

junior dean (1657), and college steward (1659 and 1660); and according

to the habit of the time, he was accustomed to preach in his college

chapel and also at Great St Mary's, long before he took holy orders on 23 December 1660. Among these sermons were his discourses on The wisdom of God manifested in the works of the creation, and Deluge and Dissolution of the World. Ray's reputation was high also as a tutor; and he communicated his own passion for natural history to several pupils, of whom Francis Willughby is by far the most famous.

When Ray found himself unable to subscribe to the Act of Uniformity 1661 he obliged to give up his fellowship in 1662, the year after Isaac Newton had entered the college. We are told by Dr Derham in his Life of Ray that the reason of his refusal was:

[...] his having taken the 'Solemn League and Covenant', for that he never did, and often declared that he ever thought it an unlawful oath; but he said he could not declare for those that had taken the oath that no obligation lay upon them, but feared there might.

From this time onwards he seems to have depended chiefly on the bounty of his pupil Willughby, who made Ray his constant companion while he lived, and at his death left him 6 shillings a year, with the charge of educating his two sons.

In the spring of 1663 Ray started together with Willughby and two other pupils on a tour through Europe, from which he returned in March 1666, parting from Willughby at Montpellier, whence the latter continued his journey into Spain. He had previously in three different journeys (1658, 1661, 1662) travelled through the greater part of Great Britain, and selections from his private notes of these journeys were edited by George Scott in 1760, under the title of Mr Ray's Itineraries. Ray himself published an account of his foreign travel in 1673, entitled Observations topographical, moral, and physiological, made on a Journey through part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy, and France. From this tour Ray and Willughby returned laden with collections, on which they meant to base complete systematic descriptions of the animal and vegetable kingdoms. Willughby undertook the former part, but, dying in 1672, left only an ornithology and ichthyology, in themselves vast, for Ray to edit; while the latter used the botanical collections for the groundwork of his Methodus plantarum nova (1682), and his great Historia generalis plantarum (3 vols., 1686, 1688, 1704). The plants gathered on his British tours had already been described in his Catalogus plantarum Angliae (1670), which work is the basis of all later English floras.

In 1667 Ray was elected Fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1669 he published in conjunction with Willughby his first paper in the Philosophical Transactions on Experiments concerning the Motion of Sap in Trees. They demonstrated the ascent of the sap through the wood of the tree, and supposed the sap to precipitate a kind of white coagulum or jelly, which may be well conceived to be the part which every year between bark and tree turns to wood and of which the leaves and fruits are made. Immediately after his admission into the Royal Society he was induced by Bishop John Wilkins to translate his Real Character into Latin, and it seems he actually completed a translation, which, however, remained in manuscript; his Methodus plantarum nova was in fact undertaken as a part of Wilkins's great classificatory scheme.

In 1673 Ray married Margaret Oakley of Launton; in 1676 he went to Sutton Coldfield, and in 1677 to Falborne Hall in Essex.

Finally, in 1679, he removed to Black Notley, where he afterwards

remained. His life there was quiet and uneventful, although he had poor

health, including chronic sores. He occupied himself in writing books

and in keeping up a wide scientific correspondence, and lived, in spite

of his infirmities, to the age of seventy-six, dying at Black Notley.

The Ray Society, for the publication of works on natural history, was founded in his honor in 1844. Ray was the first person to produce a biological definition of what a species is. This definition comes in the 1686 History of plants: Ray's works were directly influential on the development of taxonomy by Carl Linnaeus. In 1844, the Ray Society was founded, named after John Ray, and has since published over 160 books on natural history. In 1986, to mark the 300th anniversary of the publication of Ray's Historia Plantarum,

there was a celebration of Ray's legacy in Braintree. A "John Ray

Gallery" was opened in the Braintree Museum. The scientific society at

his old college, St Catharine's College, Cambridge, is named the "John Ray Society" after him.