<Back to Index>

- Inventor Charles Cros, 1842

- Novelist William Thomas Beckford, 1760

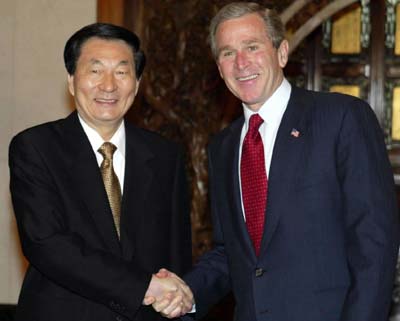

- 5th Premier of the People's Republic of China Zhū Rongjī, 1928

PAGE SPONSOR

Zhū Róngjī (pinyin: Zhū Róngjī; Wade-Giles: Chu Jung-chi; born 1 October 1928 in Changsha, Hunan) is a prominent Chinese politician who served as the Mayor and Party chief in Shanghai between 1987 and 1991, before serving as Vice - Premier and then the fifth Premier of the People's Republic of China from March 1998 to March 2003.

A

tough administrator, his time in office saw the continued double digit

growth of the Chinese economy and China's increased assertiveness in

international affairs. Known to be engaged in a testy relationship with

General Secretary Jiang Zemin,

under whom he served, Zhu provided a novel pragmatism and hard work

ethic in the government and party leadership increasingly infested by

corruption, and as a result gained great popularity with the Chinese

public. His opponents, however, charge that Zhu's tough and pragmatic

stance on policy was unrealistic and unnecessary, and many of his

promises were left unfulfilled. Zhu retired in 2003, and has not been a

public figure since. Premier Zhu was also widely known for his charisma

and tasteful humour. Zhu joined the Communist Party of China in October 1949. He graduated from the prestigious Tsinghua University in 1951 where he majored in electrical engineering and became the chairman of Tsinghua Student Union in

1951. Afterwards, he worked for the Northeast China Department of

Industries as deputy head of its production planning office. From 1952 to 1958, he worked in the State Planning Commission as group head and deputy division chief. Having criticized Mao Zedong's "irrational high growth" policies during the Great Leap Forward,

Zhu was labeled a "Rightist" in 1958 and sent to work as a teacher at a

cadre school. Pardoned (but not rehabilitated) in 1962, he worked as an

engineer for the National Economy Bureau of the State Planning

Commission until 1969. During the Cultural Revolution,

Zhu was purged again, and from 1970 to 1975 he was transferred to work

at a "May Seventh Cadre School," a type of farm used for re-education

during the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976). From

1975 to 1979, he served as the deputy chief engineer of a company run

by the Pipeline Bureau of the Ministry of Petroleum Industry and as the

director of Industrial Economics Institute under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. When Deng Xiaoping started

economic reforms in 1978, his politic looked for like minded economic

advisors and sought out Zhu. The CPC formally rehabilitated Zhu on the

strength of Zhu's forward thinking and bold economic ideas. His

membership in CPC was restored. Deng once said that Zhu "has his own

views, dares to make decisions and knows economics." Zhu went to work for the State Economic Commission (SEC)

as the division chief of the Bureau of Fuel and Power Industry and as

the deputy director of the Comprehensive Bureau from 1979 to 1982. He

was appointed as a member of the State Economic Commission in 1982 and

as the vice - minister in charge of the commission in 1983, where he held

the post until 1987, before being appointed as the mayor of Shanghai. As the mayor of Shanghai from 1989 to 1991, Zhu won popular respect and acclaim for overseeing the development of Pudong, a Singapore sized Special Economic Zone (SEZ)

wedged between Shanghai proper and the East China Sea, as well the

modernization of the city's telecommunications, urban construction, and

transport sectors. In 1991, Zhu became the vice - premier of the State Council, transferring to Beijing from Shanghai.

Also holding the post of director of the State Council Production

Office, Zhu focused on industry, agriculture and finance, launching the

drive to disentangle the "debt chains" of state enterprises. For the

sake of the peasantry, he took the lead in eliminating the use of

credit notes in state grain purchasing. Between

1993 and 1995, Zhu served as a member of the Standing Committee of the

Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee while retaining his posts

as the vice - premier of the State Council and as the governor of the People's Bank of China. From 1995 to 1998, he retained the positions of Standing Committee member and vice - premier. Concurrently

serving as governor of the Central Bank, Zhu tackled the problems of an

excessive money supply, rising prices, and a chaotic financial market

stemming, in large measure, from runaway investments in fixed assets.

After four years of successful macro - economic controls with curbing

inflation as the primary task, an overheated Chinese economy cooled

down to a "soft landing". With these achievements, Zhu, acknowledged as

an able economic administrator, became premier of the State Council. Zhu has a reputation for being a strong, strict administrator, intolerant of flunkeyism, nepotism,

and a dilatory style of work. For his hard work ethic and general

truthful and transparent attitude, he is generally considered one of

the most popular Communist officials in mainland China. With support from Jiang Zemin and Li Peng, then president and premier respectively, Zhu enacted tough macroeconomic control

measures. Favoring healthy, sustainable development, Zhu expunged

low tech, duplicated projects and sectors that would result in "a

bubble economy" and projects in transport, energy and agricultural

sectors, averting violent market fluctuations. He focused on

strengthening industry, agriculture and on continuing a moderately

tight monetary policy. He also started a large privatization program

which saw China's private sector grow massively. President Jiang Zemin nominated Zhu for the position of the Premier of the State Council at the Ninth National People's Congress (NPC), who confirmed the nomination on 17 March 1998 at the NPC First Session. Zhu was re-elected as a member of the powerful Politburo Standing Committee, China's de facto central decision making group, at the 15th CPC Central Committee in September 1997. The

1990s were a difficult time for economic management, as unemployment

soared in the cities, and the bureaucracy became increasingly tainted

with corruption scandals. Zhu kept things on track in the difficult

years of the late 1990s, so that China averaged growth of 9.7% a year

over the two decades to 2000. Against the backdrop of the Asian

financial crisis (and catastrophic domestic floods) mainland China's GDP still

grew by 7.9% in the first nine months of 2002, beating the government's

7% target despite a global economic slowdown. This was achieved,

partly, through active state intervention to stimulate demand through

wage increases in the public sector, among other measures. China was

one of the few economies in Asia that survived the crisis. While

foreign direct investment (FDI) worldwide halved in 2000, the flow of

capital into mainland China rose by 10%. As global firms scrambled to

avoid missing the China boom, FDI in China rose by 22.6% in 2002. While

global trade stagnated, growing by one percent in 2002, mainland

China's trade soared by 18% in the first nine months of 2002, with

exports outstripping imports. Despite

the glowing growth statistics, Zhu tackled deep seated structural

problems: uneven development; inefficient state firms and a banking

system mired in bad loans. Observers think there are few substantial

disagreements over economic policy in the CPC; tensions focus on the

pace of change. Zhu's economic philosophies had often triumphed over

that of his colleagues, but it nevertheless resulted in a testy

relationship with then General Secretary Jiang Zemin. The PRC leadership struggled to modernize State owned enterprises (SOEs)

without inducing massive urban unemployment. As millions lost their

jobs as state firms close, Zhu demanded financial safety nets for

unemployed workers, an important aim in a country of 1.3 billion. China

needs 100 million new urban jobs in the next five years to absorb laid

off workers and rural migrants; so far they have been achieving this

aim due to high per capita GDP growth. Under the auspices of Zhu and Wen Jiabao (his

top deputy and successor), the state tried to alleviate unemployment

while promoting efficiency, by pumping tax revenues into the economy

and maintaining consumer demand. Zhu has won acclaim domestically and

internationally for steering the People's Republic of China into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Critics

charge that there is an oversupply of manufactured goods, driving

down prices and profits while increasing the level of bad debt in the

banking system. But so far demand for Chinese goods, domestically and

abroad, is high enough to put those concerns to rest for the time being.

Consumer spending is growing, boosted, in large part, due to longer

workers' holidays. Zhu's right hand man, Vice Premier Wen Jiabao,

oversaw regulations for the stock market and campaigned to develop

poorer inland provinces to stem migration and regional resentment. Zhu,

and his successor Wen, set limits for

taxes imposed on farmers to protect them from high levies by corrupt

officials. Well respected by ordinary Chinese citizens, Zhu also holds

the respect of Western political and business leaders, who found him

reassuring and credit him with clinching China's market opening World Trade Organisation (WTO) accession, which has brought foreign capital pouring into the country. Zhu

remained as Premier until the National People's Congress met in March

2003, when it approved his struggle to clinch trusted deputy Wen Jiabao as his successor. Wen was the only Zhu ally to appear on the nine person Politburo Standing Committee. Like his fourth generation colleague Hu Jintao,

Wen's personal opinions are difficult to discern since he sticks very

closely to his script. Unlike the frank, strong willed Zhu, Wen, who

has earned a reputation for being an equally competent manager, is

known for his suppleness and discretion. During the 2000 ROC presidential election in Taiwan, Zhu gave the warning "there will be no good ending for those involved in Taiwan independence". In his farewell speech to the National People's Congress, Zhu unintentionally referred to China and Taiwan as two "countries" before quickly correcting himself. His stance on Taiwan during his time in office was always with the Party line. Zhu has a good command of English. He is rarely seen speaking from a script. In his free time, Zhu enjoys the Peking Opera. According to some reports, Zhu is a 18th generation descendent of Zhu Bian (朱楩), titled Prince Min (岷王), the 18th son of Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming Dynasty. He has a cousin, Zhu Yunzhong, who was born in 1933 and is a retired doctor. His

wife, Lao An, was once vice - chair of the board of directors of China

International Engineering and Consulting. She and Zhu were in the same

schools twice, first the Hunan First Provincial Middle School (湖南第一中学)

and then Tsinghua University. They have a son and a daughter. Zhu is known for his technical intellect. In 1997 at a state banquet in Australia,

Zhu left for the bathroom, and was gone quite a while. Concerned

security staff finally went off to find him. He was in the bathroom,

studying the water saving dual flush system which he had just

disassembled. As a hydrologist, Zhu grasped the impact such water

savings, multiplied by China's huge population, could have on China's

infrastructure.

Zhu Rongji was noticeably more popular than his predecessor,

Li Peng,

and some analysts point out that Zhu's tough administrative style in

the Premier's office bore a certain resemblance to Premier Zhou Enlai. Zhu, a competent manager and a skilled politician, ran

into various roadblocks during his tenure because of the attitude of

General Secretary Jiang Zemin. Critics charge that Zhu made too many

"big promises" that was impossible to achieve during his term in office.