<Back to Index>

- Botanist Julius von Sachs, 1832

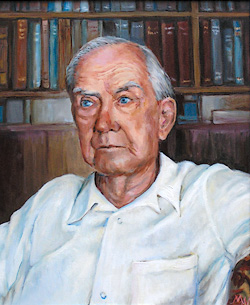

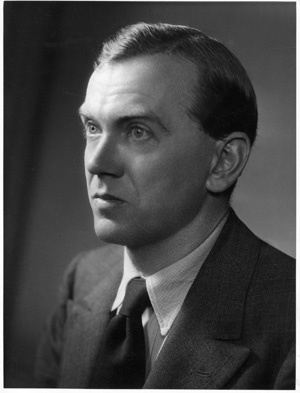

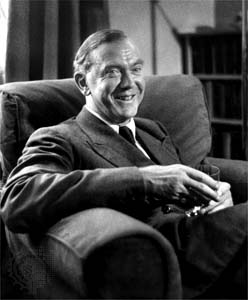

- Writer Henry Graham Greene, 1904

- Chancellor of Austria Leopold Figl, 1902

PAGE SPONSOR

Henry Graham Greene, OM, CH (2 October 1904 – 3 April 1991) was an English author, playwright and literary critic. His works explore the ambivalent moral and political issues of the modern world. Greene was notable for his ability to combine serious literary acclaim with widespread popularity.

Although Greene objected strongly to being described as a Roman Catholic novelist rather than as a novelist who happened to be Catholic, Catholic religious themes are at the root of much of his writing, especially the four major Catholic novels: Brighton Rock, The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter and The End of the Affair. Several works such as The Confidential Agent, The Third Man, The Quiet American, Our Man in Havana and The Human Factor also show an avid interest in the workings of international politics and espionage.

Greene suffered from bipolar disorder, which had a profound effect on his writing and personal life. In a letter to his wife Vivien, he told her that he had "a character profoundly antagonistic to ordinary domestic life", and that "unfortunately, the disease is also one's material".

Henry Graham Greene was born in 1904 in St. John’s House, a boarding house of Berkhamsted School on Chesham Road in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, England, when his father was housemaster there. He was the fourth of six children; his younger brother, Hugh, became Director - General of the BBC, and his elder brother, Raymond, an eminent physician and mountaineer. His parents, Charles Henry Greene and Marion Raymond Greene, were first cousins, members of a large, influential family, that included the Greene King brewery owners, bankers, and businessmen. Charles Greene was Second Master at Berkhamsted School, the headmaster of which was Dr Thomas Fry, who was married to a cousin of Charles. Another cousin was the right wing pacifist Ben Greene, whose politics led to his internment during World War II. In 1910 Charles Greene succeeded Dr. Fry as headmaster. Graham attended the school. Bullied, and profoundly depressed as a boarder, he made several suicide attempts, some, as he wrote in his autobiography, by Russian roulette. In 1920, at age 16, in what was a radical step for the time, he was psychoanalysed for six months in London, afterwards returning to school as a day student. School friends included Claud Cockburn the satirist, and Peter Quennell the historian.

In 1922 he was for a short time a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In 1925, while an undergraduate at Balliol College, Oxford, his first work, a poorly received volume of poetry entitled Babbling April, was published. Greene suffered from periodic bouts of depression whilst at Oxford, and largely kept himself to himself. Of Greene's time at Oxford, his contemporary Evelyn Waugh noted that: "Graham Greene looked down on us (and perhaps all undergraduates) as childish and ostentatious. He certainly shared in none of our revelry".

After graduating with a

second - class degree in history, he worked for a period of time as a private tutor and then turned to journalism – first on the Nottingham Journal, and then as a sub - editor on The Times. While in Nottingham he started corresponding with Vivien Dayrell - Browning,

a Catholic convert, who had written to him to correct him on a point of

Catholic doctrine. Greene was an agnostic at the time, but when he

began to think about marrying Vivien, it occurred to him that, as he

puts it in A Sort of Life,

he "ought at least to learn the nature and limits of the beliefs she

held". In his discussions with the priest to whom he went for

instruction, he argued "on the ground of dogmatic atheism", as his

primary difficulty was what he termed the "if" surrounding God's

existence. However, he found that "after a few weeks of serious

argument the 'if' was becoming less and less improbable". Greene converted to Catholicism in 1926 (described in A Sort of Life) when he was baptised in February of that year. He

married Vivien in 1927; and they had two children, Lucy Caroline (b.

1933) and Francis (b. 1936). In 1948 Greene separated from Vivien.

Although he had other relationships, he never divorced or remarried.

Greene's first published novel was The Man Within (1929). Favourable reception emboldened him to quit his sub - editor job at The Times and work as a full time novelist. The next two books, The Name of Action (1930) and Rumour at Nightfall (1932), were unsuccessful; and he later disowned them. His first true success was Stamboul Train (1932), adapted as the film Orient Express (1934).

He supplemented his novelist's income with freelance journalism, book and film reviews for The Spectator, and co-editing the magazine Night and Day, which folded in 1937. Greene's film review of Wee Willie Winkie, featuring nine year old Shirley Temple, cost the magazine a lost libel lawsuit. Greene's review stated that Temple displayed "a dubious coquetry" which appealed to "middle aged men and clergymen". It is now considered one of the first criticisms of the sexualisation of children for entertainment.

Greene originally divided his fiction into two genres: thrillers (mystery and suspense books), such as The Ministry of Fear, which he described as entertainments, often with notable philosophic edges, and literary works, such as The Power and the Glory, which he described as novels, on which he thought his literary reputation was to be based.

As his career lengthened, both Greene and his readers found the distinction between entertainments and novels increasingly problematic. The last book Greene termed an entertainment was Our Man in Havana in 1958. When Travels with My Aunt was published eleven years later, many reviewers noted that Greene had designated it a novel, even though, as a work decidedly comic in tone, it appeared closer to his last two entertainments, Loser Takes All and Our Man in Havana, than to any of the novels. Greene, they speculated, seemed to have dropped the category of entertainment. This was soon confirmed. In the Collected Edition of Greene's works published in 22 volumes between 1970 and 1982, the distinction between novels and entertainments is no longer maintained. All are novels.

Greene also wrote short stories and plays, which were well received, although he was always first and foremost a novelist. He collected the 1948 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Heart of the Matter. In 1986, he was awarded Britain's Order of Merit.

Greene was one of the most "cinematic" of twentieth century writers; most of his novels and many of his plays and short stories would eventually be adapted for film or television. The Internet Movie Database lists 66 titles based on Greene material between 1934 and 2010. Some novels were filmed more than once, such as Brighton Rock in 1947 and 2011, The End of the Affair in 1955 and 1999, and The Quiet American in 1958 and 2002. The early thriller A Gun for Sale was filmed at least five times under different titles. He also wrote several original screenplays. In 1949, after writing the novella as "raw material", he wrote the screenplay for the classic film noir, The Third Man, featuring Orson Welles. In 1983, The Honorary Consul, published ten years earlier, was released as a film under its original title, starring Michael Caine and Richard Gere. Michael Korda, the famous author and Hollywood script writer, contributed a foreword and introduction to this novel in a commemorative edition.

In 2009 The Strand Magazine began to publish in serial form a newly discovered Greene novel entitled The Empty Chair. The manuscript was written in longhand when Greene was 22 and newly converted to Catholicism. Throughout

his life Greene travelled far from England, to what he called the

world's wild and remote places. The travels led to him being recruited into MI6 by his sister, Elisabeth, who worked for the organisation; and he was posted to Sierra Leone during the Second World War. Kim Philby, who would later be revealed as a Soviet double agent, was Greene's supervisor and friend at MI6. As a novelist he wove the characters he met and the places where he lived into the fabric of his novels. Greene first left Europe at 30 years of age in 1935 on a trip to Liberia that produced the travel book Journey Without Maps. His 1938 trip to Mexico, to see the effects of the government's campaign of forced anti - Catholic secularisation, was paid for by Longman's, thanks to his friendship with Tom Burns. That voyage produced two books, the factual The Lawless Roads (published as Another Mexico in the U.S.) and the novel The Power and the Glory. In 1953 the Holy Office informed Greene that The Power and the Glory was damaging to the reputation of the priesthood; but later, in a private audience with Greene, Pope Paul VI told him that, although parts of his novels would offend some Catholics, he should not pay attention to the criticism. Greene travelled to the Haiti which was under the rule of dictator François Duvalier, known as "Papa Doc", where the story of The Comedians (1966) took place. The owner of the Hotel Oloffson in Port - au - Prince, where Greene frequently stayed, named a room in his honour. After his apparently benign involvement in a financial scandal, Greene chose to leave Britain in 1966, moving to Antibes,

to be close to Yvonne Cloetta, whom he had known since 1959, a

relationship that endured until his death. In 1973, Greene had an

uncredited cameo appearance as an insurance company representative in François Truffaut's film Day for Night. In 1981 he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize, awarded to writers concerned with the freedom of the individual in society. One of his final works, the pamphlet J'Accuse – The Dark Side of Nice (1982), concerns a legal matter embroiling him and his extended family in Nice.

He declared that organized crime flourished in Nice, because the city's

upper levels of civic government had protected judicial and police

corruption. The accusation provoked a libel lawsuit that he lost. In 1994, after his death, he was vindicated, when the former mayor of Nice, Jacques Médecin, was imprisoned for corruption and associated crimes. He lived the last years of his life in Vevey, on Lake Geneva, in Switzerland, the same town Charlie Chaplin was living in at this time. He visited Chaplin often, and the two were good friends. His book Doctor Fischer of Geneva or the Bomb Party (1980)

bases its themes on combined philosophic and geographic influences. He

had ceased going to mass and confession in the 1950s, but in his final

years began to receive the sacraments again from Father Leopoldo

Durán, a Spanish priest, who became a friend. He died at age 86

of leukemia in 1991 and was buried in Corsier - sur - Vevey cemetery. Greene's literary agent was Jean LeRoy of Pearn, Pollinger & Higham.

The literary style of Graham Greene was described by Evelyn Waugh in Commonweal as

"not a specifically literary style at all. The words are functional,

devoid of sensuous attraction, of ancestry, and of independent life".

Commenting on this lean, realistic prose and its readability, Richard

Jones wrote in the Virginia Quarterly Review that "nothing deflects Greene from the main business of holding the reader's attention." His novels often have religious themes at the centre. In his literary criticism he attacked the modernist writers Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster for

having lost the religious sense which, he argued, resulted in dull,

superficial characters, who "wandered about like cardboard symbols

through a world that is paper - thin". Only

in recovering the religious element, the awareness of the drama of the

struggle in the soul carrying the infinite consequences of salvation

and damnation, and of the ultimate metaphysical realities of good and evil, sin and divine grace,

could the novel recover its dramatic power. Suffering and unhappiness

are omnipresent in the world Greene depicts; and Catholicism is

presented against a background of unvarying human evil, sin, and doubt. V.S. Pritchett praised Greene as the first English novelist since Henry James to present, and grapple with, the reality of evil. Greene

concentrated on portraying the characters' internal lives – their

mental, emotional, and spiritual depths. His stories often occurred in

poor, hot, and dusty tropical backwaters, such as Mexico, West Africa,

Vietnam, Cuba, Haiti, and Argentina, which led to the coining of the

expression "Greeneland" to describe such settings.

The

novels often powerfully portray the Christian drama of the struggles

within the individual soul from the Catholic perspective. Greene was

criticised for certain tendencies in an unorthodox direction – in the

world, sin is omnipresent to the degree that the vigilant struggle to

avoid sinful conduct is doomed to failure, hence not central to

holiness. Friend and fellow Catholic

Evelyn Waugh attacked that as a revival of the Quietist heresy. This aspect of his work also was criticised by the theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar,

as giving sin a mystique. Greene responded that constructing a vision

of pure faith and goodness in the novel was beyond his talents. Praise

of Greene from an orthodox Catholic point of view by Edward Short is in Crisis Magazine, and a mainstream Catholic critique is presented by Joseph Pearce. Catholicism's prominence decreased in the later writings. According to Ernest Mandel in his Delightful Murder: a Social History of the Crime Story:

"Greene started out as a conservative agent of the British intelligence

services, upholding such reactionary causes as the struggle of the

Catholic Church against the Mexican revolution (The Power and the Glory, 1940), and arguing the necessary merciful function of religion in a context of human misery (Brighton Rock, 1938; The Heart of the Matter,

1948). The better he came to know the socio - political realities of the

third world where he was operating, and the more directly he came to be

confronted by the rising tide of revolution in those countries, the

more his doubts regarding the imperialist cause grew, and the more his

novels shifted away from any identification with the latter." The supernatural realities that haunted the earlier work declined and were replaced by a humanistic perspective, a change reflected in his public criticism of orthodox Catholic

teaching. Left wing political critiques assumed greater importance in

his novels: for example, years before the Vietnam War, in The Quiet American he

prophetically attacked the naive and counter productive attitudes that

were to characterize American policy in Vietnam. The tormented

believers he portrayed were more likely to have faith in communism than

in Catholicism. In his later years Greene was a strong critic of American imperialism, and supported the Cuban leader Fidel Castro, whom he had met. In Ways of Escape, reflecting on his Mexican trip, he complained that Mexico's government was insufficiently left wing compared with Cuba's. In Greene's opinion, "Conservatism and Catholicism should be .... impossible bedfellows". —Graham Greene Despite his seriousness, Graham Greene greatly enjoyed parody, even of himself. In 1949, when the New Statesman held

a contest for parodies of Greene's writing style, he submitted an entry

under the pen name "N. Wilkinson" and won second prize. His entry

comprised the first two paragraphs of a novel, apparently set in Italy, The Stranger's Hand: An Entertainment. Greene's friend, Mario Soldati, a Piedmontese novelist and film director, believed that it had the makings of a suspense film about Yugoslav spies in postwar Venice.

Upon Soldati's prompting, Greene continued writing the story as the

basis for a film script. Apparently he lost interest in the project,

leaving it as a substantial fragment that was published posthumously in The Graham Greene Film Reader (1993) and No Man's Land (2005). The script for The Stranger's Hand was

penned by veteran screenwriter Guy Elmes on the basis of Greene's

unfinished story, and cinematically rendered by Soldati. In 1965 Greene

again entered a similar New Statesman competition pseudonymously, and won an honourable mention.

The

Graham Greene International Festival is an annual four - day event of

conference papers, informal talks, question and answer sessions, films,

dramatised readings, music, creative writing workshops and social

events. It is organised by the Graham Greene Birthplace Trust, and

takes place in the writer's home town of Berkhamsted, on dates as close

as possible to the anniversary of his birth. Its purpose is to promote

interest in and study of the works of Graham Greene.

“ In human relationships, kindness and lies are worth a thousand truths. ”