<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Øystein Ore, 1899

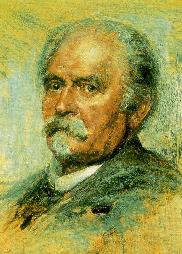

- Composer Felix August Bernhard Draeseke, 1835

- Labor Activist Joel Emmanuel Hägglund (Joe Hill), 1879

PAGE SPONSOR

Felix August Bernhard Draeseke (October 7, 1835 – February 26, 1913) was a composer of the "New German School" admiring Liszt and Richard Wagner. He wrote compositions in most forms including eight operas and stage works, four symphonies, and much vocal and chamber music.

Felix Draeseke was born in the Franconian ducal town of Coburg, Germany. He was attracted to music early in life and wrote his first composition at age 8. He encountered no opposition from his family when, in his mid-teens, he declared his intention of becoming a professional musician. A few years at the Leipzig conservatory did not seem to benefit his development, but after one of the early performances of Wagner's Lohengrin he was won to the camp of the New German School centered around Franz Liszt at Weimar, where he stayed from 1856 (arriving just after Joachim Raff's departure) to 1861. In 1862 Draeseke left Germany and made his way to Switzerland, teaching in the Suisse Romande in the area around Lausanne. Upon his return to Germany in 1876, Draeseke chose Dresden as his place of residence. Though he continued having success in composition, it was only in 1884 that he received an official appointment to the Dresden conservatory and, with it, some financial security. In 1894, two years after his promotion to a professorship at the Royal Saxon Conservatory, at the age of 58, he married his former pupil Frida Neuhaus. In 1912 he completed his final orchestral work, the Fourth Symphony. On February 26, 1913, Draeseke suffered a stroke and died; he is buried in the Tolkewitz cemetery in Dresden.

During his career Draeseke divided his efforts almost equally among compositional realms and composed in most genres, including symphonies, concertos, opera, chamber music, and works for solo piano. With his early Piano Sonata in c-sharp Sonata quasi Fantasia of 1862 – 1867 he aroused major interest, winning Liszt's unreserved admiration of it as one of the most important piano sonatas after Beethoven. His operas Herrat (1879, originally Dietrich von Bern) and Gudrun (1884, after the medieval epic of the same name) met with some success, but their subsequent neglect has kept posterity from understanding Draeseke as one of the few true successors to Wagner and one of the very few who could conceive dramatically convincing and musically compelling examples of "Gesamtkunstwerk".

Draeseke keenly followed new developments in all facets of music. His chamber music compositions make use of newly developed instruments, among them the violotta, an instrument developed by Alfred Stelzner as an intermediary between viola and cello, which Draeseke used in his A major String Quintet, and also the viola alta, an instrument developed during the 1870s by Hermann Ritter and the prototype of viola expressly endorsed by Richard Wagner for his Bayreuth Orchestra.

A master contrapuntist,

Draeseke reveled in writing choral music, achieving major success with

his B minor Requiem of 1877 – 1880, but nowhere proving more convincingly

his powers in this direction than in the staggering Mysterium Christus which is composed of a prolog and three separate oratorios and

requires three days for a complete performance, a work which occupied

him between the years 1894 – 1899 but whose conception reaches back to

the 1860s. Of all the symphonies from the second half of the 19th

century which are unjustly neglected, Draeseke's Symphonia Tragica (Symphony No. 3 in C major, op. 40) is one of the very few which deserves repertory status alongside the symphonies of Brahms and Bruckner,

a masterful fusion of intellect and emotion, of form and content.

Orchestral works like the Serenade in F major (1888) or its companion

of the same year, the symphonic prelude after Kleist's Penthesilea have

in them all that is declared necessary for audience success: rich

melodic invention, rhythmic vivacity, and extraordinary harmonic

conception. Draeseke's chamber music is equally rich. During

his life, and the period shortly following his death, the music of

Draeseke was held in high regard, even among his musical opponents. His

compositions were performed frequently in Germany by the leading

artists of the day, including Hans von Bülow, Arthur Nikisch, Fritz Reiner, and Karl Böhm.

However, as von Bülow once remarked to him, he was a "harte

Nuß" ("a hard nut to crack") and despite the quality of his

works, he would "never be popular among the ordinary". Draeseke could

be sharply critical and this sometimes led to strained relations, the

most notorious instance being with Richard Strauss, when Draeseke attacked Strauss’s Salome in his 1905 pamphlet Die Konfusion in der Musik — rather odd as Draeseke was a clear influence on the young Strauss. Draeseke's music was promoted during the Third Reich.

After the Second World War, changes in fashion and political climates

allowed his name and music to slip into obscurity. But as the 20th

century ended, new recordings spurred a renewed interest in his music.

An ever widening audience seems to be developing for Draeseke at last

and the phenomenon is based on perception of individuality,

inventiveness and stylistic integrity, music which truly rewards

attention.