<Back to Index>

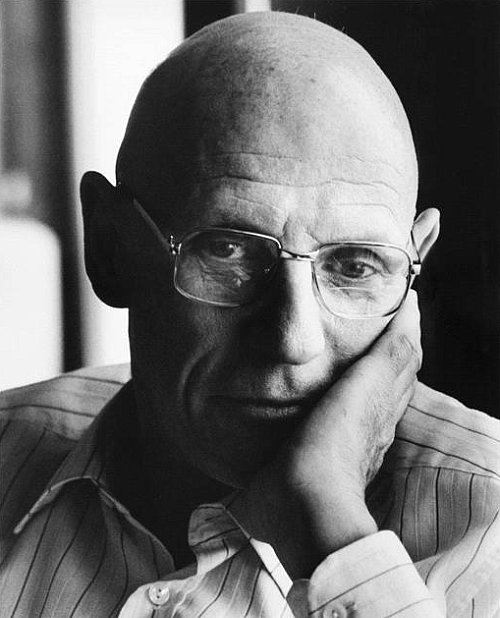

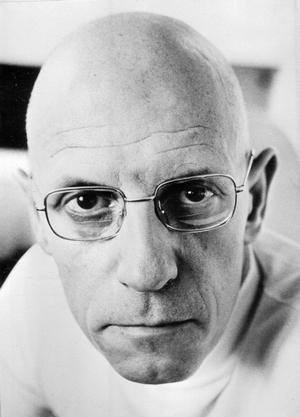

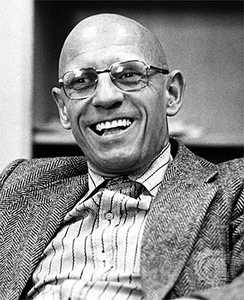

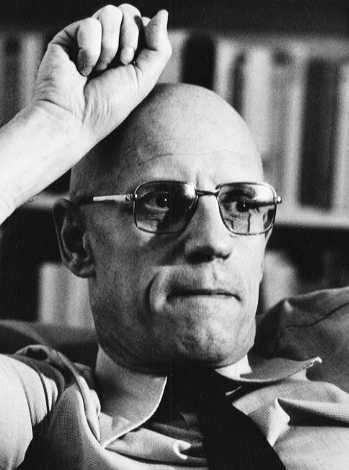

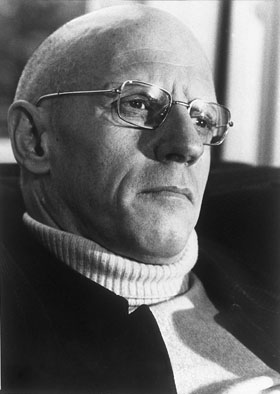

- Philosopher Michel Foucault, 1926

- Poet Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov, 1814

- 3rd President of Austria Wilhelm Miklas, 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

Michel Foucault (born Paul - Michel Foucault; 15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984), was a French philosopher, social theorist and historian of ideas. He held a chair at the prestigious Collège de France with the title "History of Systems of Thought," and also taught at the University at Buffalo and the University of California, Berkeley.

Foucault is best known for his critical studies of social institutions, most notably psychiatry, medicine, the human sciences, and the prison system, as well as for his work on the history of human sexuality. His writings on power, knowledge, and discourse have been widely influential in academic circles. In the 1960s Foucault was associated with structuralism, a movement from which he distanced himself. Foucault also rejected the post structuralist and post modernist labels later attributed to him, preferring to classify his thought as a critical history of modernity rooted in Kant. Foucault's project was particularly influenced by Nietzsche, his "genealogy of knowledge" being a direct allusion to Nietzsche's "genealogy of morality". In a late interview he definitively stated: "I am a Nietzschean." Foucault was listed as the most cited scholar in the humanities in 2007 by the ISI Web of Science.

Paul-Michel Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in Poitiers, France, to a notable provincial family. His father, Paul Foucault, was an eminent surgeon and hoped his son would join him in the profession. His early education was a mix of success and mediocrity until he attended the Jesuit Collège Saint - Stanislas, where he excelled. During this period, Poitiers was part of Vichy France and later came under German occupation. Foucault got to learn philosophy with Louis Girard.

After World War II, Foucault was admitted to the prestigious École Normale Supérieure (rue d'Ulm), the traditional gateway to an academic career in the humanities in France. Foucault's personal life during the École Normale was difficult — he suffered from acute depression. As a result, he was taken to see a psychiatrist. During this time, Foucault became fascinated with psychology. He earned a licence (degree

equivalent to BA) in psychology, a very new qualification in France at

the time, in addition to a degree in philosophy, in 1952. He was

involved in clinical psychology, which exposed him to thinkers such as Ludwig Binswanger. Foucault was a member of the French Communist Party from 1950 to 1953. He was inducted into the party by his mentor Louis Althusser, but soon became disillusioned with both the politics and the philosophy of the party. Various people, such as historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, have reported that Foucault never actively participated in his cell, unlike many of his fellow party members. Foucault failed at the agrégation in

1950 but took it again and succeeded the following year. After a brief

period lecturing at the École Normale, he took up a position at

the Université Lille Nord de France, where from 1953 to 1954 he taught psychology. In 1954 Foucault published his first book, Maladie mentale et personnalité, a

work he later disavowed. At this point, Foucault was not interested in

a teaching career, and undertook a lengthy exile from France. In 1954

he served France as a cultural delegate to the University of Uppsala in Sweden (a position arranged for him by Georges Dumézil,

who was to become a friend and mentor). He submitted his doctoral

thesis in Uppsala, but it was rejected there. In 1958 Foucault left

Uppsala and briefly held positions at Warsaw University and at the University of Hamburg. Foucault returned to France in 1960 to complete his doctorate and take up a post in philosophy at the University of Clermont - Ferrand. There he met philosopher Daniel Defert, who would become his lover of twenty years. In 1961 he earned his doctorate by submitting two theses (as is customary in France): a "major" thesis entitled Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique (Madness and Insanity: History of Madness in the Classical Age) and a "secondary" thesis that involved a translation of, and commentary on Kant's Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Folie et déraison (Madness and Insanity – published in an abridged edition in English as Madness and Civilization and

finally published unabridged as "History of Madness" by Routledge in

2006) was extremely well received. Foucault continued a vigorous

publishing schedule. In 1963 he published Naissance de la Clinique (Birth of the Clinic), Raymond Roussel, and a reissue of his 1954 volume (now entitled Maladie mentale et psychologie or, in English, "Mental Illness and Psychology"), which again, he later disavowed. After Defert was posted to Tunisia for his military service, Foucault moved to a position at the University of Tunis in 1965. He published Les Mots et les choses (The Order of Things) during the height of interest in structuralism in 1966, and Foucault was quickly grouped with scholars such as Jacques Lacan, Claude Lévi - Strauss, and Roland Barthes as the newest, latest wave of thinkers set to topple the existentialism popularized by Jean - Paul Sartre.

Foucault made a number of skeptical comments about Marxism, which

outraged a number of left wing critics, but later firmly rejected the

"structuralist" label. He was still in Tunis during

the May 1968 student riots, where he was profoundly affected by a local

student revolt earlier in the same year. In the Autumn of 1968 he

returned to France, where he published L'archéologie du savoir (The Archaeology of Knowledge) – a methodological treatise that included a response to his critics – in 1969. In the aftermath of 1968, the French government created a new experimental university, Paris VIII, at Vincennes and appointed Foucault the first head of its philosophy department in December of that year. Foucault appointed mostly young leftist academics (such as Judith Miller)

whose radicalism provoked the Ministry of Education, who objected to

the fact that many of the course titles contained the phrase

"Marxist - Leninist," and who decreed that students from Vincennes would

not be eligible to become secondary school teachers. Foucault notoriously also joined students in occupying administration buildings and fighting with police. Foucault's tenure at Vincennes was short lived, as in 1970 he was elected to France's most prestigious academic body, the Collège de France,

as Professor of the History of Systems of Thought. His political

involvement increased, and his partner Defert joined the ultra Maoist Gauche Proletarienne (GP). Foucault helped found the Prison Information Group (French: Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons or

GIP) to provide a way for prisoners to voice their concerns. This

coincided with Foucault's turn to the study of disciplinary

institutions, with a book, Surveiller et Punir (Discipline and Punish),

which "narrates" the micro - power structures that developed in Western

societies since the 18th century, with a special focus on prisons and

schools. In the late 1970s, political activism in France trailed off with the disillusionment of many left wing intellectuals. A number of young Maoists abandoned their beliefs to become the so-called New Philosophers, often citing Foucault as their major influence, a status Foucault had mixed feelings about. Foucault in this period embarked on a six volume project The History of Sexuality, which he never completed. Its first volume was published in French as La Volonté de Savoir (1976), then in English as The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (1978).

The second and third volumes did not appear for another eight years,

and they surprised readers by their subject matter (classical Greek and

Latin texts), approach and style, particularly Foucault's focus on the

human subject, a concept that some mistakenly believed he had

previously neglected. Foucault began to spend more time in the United States, at the University at Buffalo (where he had lectured on his first ever visit to the United States in 1970) and especially at UC Berkeley. In 1975 he took LSD at Zabriskie Point in Death Valley National Park, later calling it the best experience of his life. In 1979 Foucault made two tours of Iran, undertaking extensive interviews with political protagonists in support of the new interim government established soon after the Iranian Revolution. In the tradition of Nietzsche and Georges Bataille,

Foucault had embraced the artist who pushed the limits of rationality,

and he wrote with great passion in defense of irrationalities that

broke boundaries. In 1978, Foucault found such transgressive powers in

the revolutionary figures Ayatollah Khomeini and Ali Shariati whom

he referred to as the "idealogue and architect of the Islamic

revolution" and also the millions who risked death as they followed

them in the course of the revolution. Later on when Foucault went to

Iran “to be there at the birth of a new form of ideas”, he wrote that

the new “Muslim” style of politics could signal the beginning of a new

form of “political spirituality,” not just for the Middle East, but

also for Europe, which had adopted a secular politics ever since the French Revolution. Foucault recognized the enormous power of the new discourse of militant Islam, not just for Iran, but for the world. He wrote: As

an Islamic movement, it can set the entire region afire, overturn the

most unstable regimes, and disturb the most solid. Islam which is not

simply a religion, but an entire way of life, an adherence to a history

and a civilization, has a good chance to become a gigantic powder keg,

at the level of hundreds of millions of men. . . Indeed, it is also

important to recognize that the demand for the 'legitimate rights of

the Palestinian people' hardly stirred the Arab peoples. What it be if

this cause encompassed the dynamism of an Islamic movement, something

much stronger than those with a Marxist, Leninist, or Maoist character?

(“A Powder Keg Called Islam”) During

his two trips to Iran, Foucault was commissioned as a special

correspondent of a leading Italian newspaper and his articles appeared

on the front page of that paper. His many essays on Iran, published in

the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera,

only appeared in French in 1994 and then in English in 2005. These

essays caused some controversy, with some commentators arguing that

Foucault was insufficiently critical of the new regime. The more common

attempts to bracket out Foucault's writings on Iran as

"miscalculations," reminds some authors of what Foucault himself had

criticized in his well known 1969 essay, "What is an Author?"

Foucault believed that when we include certain words in an author's

career and exclude others that were written in a "different style," or

were "inferior" (Foucault 1969), we create a stylistic unity and a

theoretical coherence. This is done by privileging certain writings as

authentic and excluding others that do not fit our view of what the

author ought to be: "The author is therefore the ideological figure by

which one marks the manner in which we fear the proliferation of

meaning" (Foucault 1969). This controversy is frequently discussed in

the Foucault literature. In

the philosopher's later years, interpreters of Foucault's work

attempted to engage with the problems presented by the fact that the

late Foucault seemed in tension with the philosopher's earlier work.

When this issue was raised in a 1982 interview, Foucault remarked "When

people say, 'Well, you thought this a few years ago and now you say

something else,' my answer is… [laughs] 'Well, do you think I have

worked hard all those years to say the same thing and not to be

changed?'" He

refused to identify himself as a philosopher, historian, structuralist,

or Marxist, maintaining that "The main interest in life and work is to

become someone else that you were not in the beginning." In

a similar vein, he preferred not to claim that he was presenting a

coherent and timeless block of knowledge; he rather desired his books

"to be a kind of tool box others can rummage through to find a tool

they can use however they wish in their own area… I don't write for an

audience, I write for users, not readers." In 1992 James Miller published

a biography of Foucault that was greeted with controversy in part due

to his claim that Foucault's experiences in the gay sadomasochism

community during the time he taught at Berkeley directly influenced his

political and philosophical works. Miller's book has largely been rebuked by Foucault scholars as being either simply misdirected, a sordid reading of his life and works, or as a politically motivated, intentional misreading. Most commentators attach no political significance to Foucault's sexual behaviors. Foucault

died of an AIDS related illness in Paris on 25 June 1984. He was the

first high profile French personality who was reported to have AIDS.

Little was known about the disease at the time and there has been some controversy since. In the front page article of Le Monde announcing

his death, there was no mention of AIDS, although it was implied that

he died from a massive infection. Prior to his death, Foucault had

destroyed most of his manuscripts, and in his will had prohibited the

publication of what he might have overlooked.